A Review of Health Benefits of Fermented Munkoyo, Chibwantu Beverages And Medicinal Application of Rhynchosia Roots

*Corresponding Author(s):

Sydney PhiriZambia Agriculture Research Institute (ZARI), Private Bag 7, Chilanga Zambi, Zambia

Email:nysydph@mail.com

Abstract

Fermented cereal-based beverages made from Maize, Sorghum, Pear millet and Finger millet play a crucial role in attaining food and nutrition security in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Many such different spontaneously traditional fermented beverages have been processed and consumed for a long time in Africa. They have received more attention as energy beverages, their ability to reduce spoilage from pathogenic bacteria, growing recommendation as weaning beverages and availability of cereal grain as raw material for processing. Munkoyo and Chibwantu in particular are used as energy beverages in marriage cerebrations, funeral ceremonies and many other social gatherings in Zambia.

Munkoyo and Chibwantu are occasionally administered for health benefits to children. This is because these beverages undergo spontaneous fermentation that result in diverse microbial community, some of which are potential probiotics that provide health benefits in the Gut Intestinal Tract (GIT). Munkoyo and Chibwantu are also used to induce lactation (as galactogogues) in mothers with difficulties to produce breast milk for their newly born babies. This is possibly due to changes in nutrition and chemical composition of Munkoyo and Chibwantu as a result of spontaneous fermentation and the presence of phytochemicals from Rhynchosia roots.

This review investigates Munkoyo and Chibwantu beverages to provide probiotics and galactogogues as health benefits and medicinal application of Rhynchosia roots.

Keywords

Chibwantu; Galactogogues; Health benefits; Medicinal application; Munkoyo; Probiotics; Rhynchosia roots

Introduction

Munkoyo and Chibwantu are the two most common homemade cereal-based spontaneously fermented beverages in Zambia. The two beverages follow similar processing steps of cooking to gelatinize starch, addition of Rhynchosia roots or root extract to hydrolyze the gelatinized starch and spontaneous fermentation by microorganisms to produce desired sensorial attributes. The major differences in the processing of Munkoyo and Chibwantu are the types of maize meal and the roots used. Munkoyo generally use fine maize meal and yellow Rhynchosia roots that are completely immersed in the gelatinized starch at lower temperatures between 45oC - 55oC [1]. Chibwantu on the other hand uses grits cooked until gelatinization of starch is attained. White root extract is commonly added to gelatinized grits at similar temperatures (45oC-55oC) rather than immersing the whole root in cooked grits. The Rhynchosia root or its extract hydrolyse gelatinized starch into fermentable sugars to facilitate spontaneous fermentation by the bacteria. Spotaneous fermentation leads to non-uniform sensory attributes and food safety concerns of Munkoyo and Chibwantu that has consequently discouraged high consumption of the beverage. The only measure of safety in many traditionally fermented beverages however, is reduced pH to less than 4, that is known to reduce proliferation of pathogenic bacteria [2].

Research has revealed that fermentation is mostly done by Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB). The most prevalent being Lactobacillus, Streptococcus, Lactococcus, Leuconostoc etc. [3]. These bacteria are generally considered as ‘safe’ bacteria because they do not cause health problems, but rather promote health. These bacteria interact with other microorganism in the GIT and complement each other’s effort in digesting the food [4,5]. This is the more reason why Munkoyo and Chibwantu are considered as weaning beverages.

Research further indisputably show that high intake of fermented foods increase lactic acid bacteria and probiotics in the GIT that are beneficial to health [6] Specific examples of beneficial effects of LAB point to reduced severity and improved bowel movement frequency in constipated but healthy people after consumption of fermented foods containing Lactobacillus Casei strain Shirota [7]. It is within that context that Munkoyo and Chibwantu are considered important beverages to promote health.

Rhynchosia roots and its extract are commoly used for processing Munkoyo and Chibwantu. However, in rural communities these roots or their extract are an important traditional medicine curing several ailments. This is because Rhynchosia root species are known to contain a lot of flavonoids and antioxidants that are anti-inflammatory, antimycobacterial and antiproliferative in nature [8,9].

Unique Features Of Munkoyo And Chibwantu

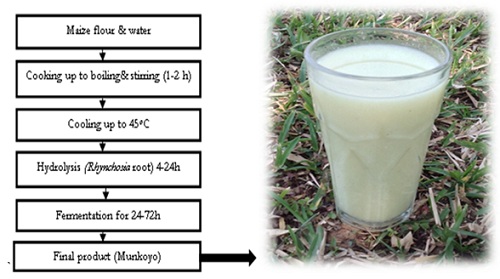

Maize, Sorghum, Pearl millet and Finger millet are the most common cereals used in the processing of cereal-based beverages in Africa, with maize topping the list. Examples of these cereal-based beverages include Mawe in Benin, Togwa in Tanzania, Maheu in Zimbabwe and Kenkey in Ghana, [1,10]. The major similarities in many of these beverages including Munkoyo and Chibwantu are cooking and spontaneous fermentation. Cooking gelatinizes the starch to facilitate hydrolysis by amylase enzymes and spontaneous fermentation is mostly dominated by lactic acid bacteria. Figure 1 below gives a generic production process of most cereal-based beverages including Munkoyo and Chibwantu [1].

Figure 1: General processing steps for making Munkoyo and Chibwantu. Maize flour/grits mixed with water at warm temperature, cook to gelatinize the starch, followed by hydrolysis of the starch by enzymes from the Rhynchosia roots and finally spontaneous fermentation by lactic acid bacteria.

Figure 1: General processing steps for making Munkoyo and Chibwantu. Maize flour/grits mixed with water at warm temperature, cook to gelatinize the starch, followed by hydrolysis of the starch by enzymes from the Rhynchosia roots and finally spontaneous fermentation by lactic acid bacteria.

Despite this generic production process, there are crucial differences in the processing steps of Munkoyo and Chibwantu from other cereal-based beverages across Africa. For example, the processing steps of Ogi in Nigeria and possibly its taste is different from Maheu produced in Zimbabwe. Maheu uses dry maize meal cooked first to gelatinize the starch before spontaneous fermentation which is done by LAB like Lactococcus Lactis sub-species [11], whilst Ogi is first steeped in earth ware or plastic bucket for 1 to 3 days and then LAB, yeast and moulds spontaneously ferment the steeped grain dominated by Corynebacterium, Saccharomyces and Candida species [12].

Table 1 below gives a summary of different cereal-based beverages in Africa, different raw materials used, commonly identified micro flora species participating in spontaneous fermentation and relative physico-chemical analysis that may contribute to the variation in the sensorial attributes of the beverages.

|

Beverage |

Country |

Raw material |

Micro flora Strains |

pH/Tit. acidity |

|

Mawe |

Benin |

Maize, millet |

Lactobacillus spp. and yeast spp. |

4.2 / 1.40% |

|

Kirario |

Kenya |

Green maize,sorghum |

Lactococci, Streptococci, Saccharomyces |

3.3 / 3.15% |

|

Maheu |

South Africa |

Maize,Sorghum, wheat |

Lactococcus lactis subsp. Lactis |

3.0 / 3.50% |

|

Togwa |

Tanzania |

Maize flour, millet malt |

L.Brevis,L.Fermentum,Candida Saccharomyces Cerevisiae, |

3.1 / 3.25% |

|

Mangisi |

Zimbabwe |

Maize and millet

|

Lactococcus lactis, Lactobacillus Sacchoromyces cerevisiae |

3.9 / 0.6% |

|

Kwete |

Uganda |

Maize, Malted millet |

W. Confusus, L. plantarum,P. pentosaceus |

3.4 / 1.42% |

|

Ogi |

Nigeria |

Maize, Sorghum, millet |

Lactobacillus,Corynebacterium,spp., Aerobacter , S. Cerevisiae, Candida |

3.6 / 0.65% |

|

Kenkey |

Ghana |

Maize, sorghum, millet |

Lactobacillus fermentum and reuteri) (Candida, penicillium, fasurium) |

3.2 / 1.20% |

Table 1: Traditional cereal-based fermented beverages in Africa.

Despite differences in the bacteria fermenting these beverages, the outstanding similarity is that maize is the common raw material and the malt of Maize, Sorghum or Millets provide amylase enzymes that hydrolyze starch into fermentable sugars prior to spontaneous fermentation. The unique feature of Munkoyo and Chibwantu over other cereal-based beverages across Africa is the use of Rhynchosia roots to provide amylase enzymes rather than using the malt.

Rhynchosia root is a special root endemic to Zambia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Zimbabwe, Angola, Tanzania, Malawi, Namibia, Botswana and Mozambique [13]. It is also a native dominant shrub in the region between Lake Tanganyika and Lake Mweru [14]. The genus name of this root and the related species is Rhynchosia, thus conveniently referred to as Rhynchosia root [15]. Traditionally, the Rhynchosia root is called Munkoyo root from which the name ‘Munkoyo’ as a beverage is derived. The processing of Munkoyo and Chibwantu beverage cannot be achieved without the use of Rhynchosia roots as an ingredient. This is because Rhynchosia root is primarily the source of amylase enzymes needed for hydrolysis of starch. Hydrolysis is an enzyme-catalyzed process in which long chain of starch are broken down into simpler fermentable sugars like maltose, glucose and maltotrioes [16]. Unlike all other spontaneously fermented beverages across Africa that use malt for the supply of enzymes, Munkoyo produced in Zambia and Democratic Republic of Congo use Rhynchosia root to supply similar amylase enzymes. It is in that context that Maize-based Munkoyo and Chibwantu displays a unique processing step over other cereal-based beverages across Africa.

Spontaneous Fermentation of Munkoyo and Chibwantu

Spontaneous fermentation naturally takes place without a starter culture. The availability of fermentable sugars after hydrolysis of starch by amylase enzymes enables spontaneous fermentation process by LAB. In most cases natural flora cultured over time through back slopping process in regularly used containers or calabashes have successfully spontaneously fermented cereal-based beverages [17]. Many microorganisms may be present during spontaneous fermentation but very few, mostly LAB dominate the micro flora. This is because not all bacteria can survive acidic condition of cereal-based fermented beverages. The common fermenting bacteria identified are species of Leuconostoc, Lactobacillus, Streptococcus, Pediococcus, Micrococcus and Bacillus apart from possible yeast species like Saccharomyces and Candida,[18,19].

Spontaneous fermentation of Munkoyo and Chibwantu on gelatinized starch is dominated by lactic acid bacteria very important to extend the shelf life, improve texture, give appealing taste and aroma [20]. However, variation in the LAB participating in spontaneous fermentation of Munkoyo and Chibwantu from one processor to the other in different regions leads to non-uniform sensorial attributes. Standardizing the process to attain controlled fermentation through starter culture rather than spontaneous fermentation could be a sure way to have consistent microbial community, predicted appealing sensory attributes with possibly probiotics. The LAB and probiotics can thus supplement gut microbiota to improve health of the consumers.

Spontaneous fermentation of Munkoyo and Chibwantu produce several volatile compounds which contribute to a complex blend of flavours in the beverage [21].The presence of aroma compounds such as diacetyl, acetic acid and butuyric acid make fermented cereal-based products more appealing, [18]. Table 2 below provides an overview of some of the most important organic acids, alcohols, aldehydes, ketones and carbonyl compounds in Munkoyo beverage that produce desirable aroma compounds and appealing sensorial attributes.

|

Organic acids |

Alochols |

Aldehydes and ketones |

Carbonyl compounds |

|

Butyric Heptanoic |

Ethanol |

Acetaldehyde |

Furfural |

|

Succinic Isovaleric |

n-propanol |

Formaldehyde |

Methional |

|

Formic Propionic |

isobutanol |

Isovaleraldehyde |

Glyoxal |

|

Valeric n-Butytric |

Amyl alcohol |

n-Valderaldehyde |

3- Methyl butanal |

|

Caproic Isoburyric |

2,3 Butandieol |

2-methyl butanol |

2- Methyl butanal |

|

Lactic Caprylic |

B-phenylethyl alcohol |

n- Hexaldehyde |

Hydroxyl-methl furtural |

|

Acetic Isocaprilic |

|

Acetone |

|

|

Capric Pleagronic |

|

Propionaldehyde |

|

|

Pyruvic Mevulinic |

|

Iso butyraldehyde |

|

|

Palmitic Myristic |

|

Methylethyl ketone |

|

|

Crotonic Hydrocinnamic |

|

Butanone |

|

|

Itaconic Benzylic |

|

Diacetyl |

|

|

Lauric |

|

Acetone |

|

Table 2: Aroma compounds in fermented Munkoyo beverage [1].

Probiotic Bacteria In Munkoyo And Chibwantu

There is an increase in awareness globally on the health benefits of good nutrition. Fermented foods are gaining that awareness because of the presence of ’safe’ LAB some of which are probiotics. Probiotics are microorganisms that interact with the micro flora in the gut microbiota to provide various health benefits. FAO/WHO 2002 defines probiotics as live microorganisms in food stuffs, when consumed at certain levels stabilize the GIT micro flora providing health benefits on the consumer [22].The benefits range from suppressing pathogens to synthesizing micronutrients and vitamins. Probiotics are commonly cultured in milk based fermented products like yogurt and cheese. Starter cultures used may contain selected microorganism that promote good nutrition and health. Examples of probiotics identified in milk-based foods belong to the genera Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Lactococcus and Enterococcus [23].

Much as dairy products provide suitable environment to culture probiotics, milk allergies, lactose intolerance or high cholesterol are major downsides of diary-based products to provide probiotics. This downside provides an opportunity for non-diary food products like cereal-based beverages to culture probiotic bacteria as well. Cereal-based spontaneously fermented beverages already provide a unique advantage considering diverse microbial community fermenting the beverage, with already identified potential probiotics. They also serve as efficient transporters of Lactobacilli bacteria species in the GIT and can stimulate the growth of single and mixed cultures of probiotic bacteria [24].

A very good example of a cereal-based beverage in Africa that has been studied to contain probiotics is Ogi from Nigeria. Ogi is traditionally prepared by spontaneously fermenting water-steeped maize grain for 2-4 days at room temperature, [25]. Ogi has been recommended in many parts of Nigeria by nursing mothers as a therapy food given to weaned babies to terminate diarrhea and other abdominal discomforts. Evaluated the anti-bacterial effect of Ogi against common diarrheal and discovered the inhibition of pathogens by potential probiotic bacteria dominated by Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactobacillus fermentum and Streptococcus [26].

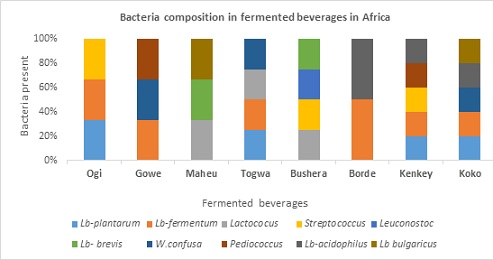

Cereal grains including sorghum, maize and millet are common substrate for lactic acid fermented beverages such as Togwa in Tanzania. Fermentation of Togwa is basically spontaneous resulting in product variability. On the other hand, spontaneous fermentation by lactic acid bacteria has attracted attention due to microbial stability, improved nutrition qualities and probiotic potential [2]. The LAB isolated from Togwa include L plantarum, L. Brevis, L. Fermentum, W. Confusa known to have probiotic potential [27]. Other bacteria species with similar probiotic characteristics in different traditional fermented beverages across Africa are shown in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2: Microbial composition of spanteneously fermented beverages with probiotic potential.

A study of Munkoyo and Chibwantu by Schoustra et al., 2013 retrieved multiple strains of bacteria although Lactobacillus was the most abundant genus found, followed by members of Leuconostoc, Lysinibacillus and Bacillus genera [28]. Another profiling of microbial diversity in fermented cereal-based Munkoyo beverage, revealed that the most dominate microbial species were Stroptococceae, Leuconostocaceae, Enterobacteriaceaea, Lactobacillales, Bacilluceae and Aeromonadecea [29]. A comparison of microbial diversity of Munkoyo and Chibwantu with the most abundant probiotic bacteria across Africa as indicated in fig.2, show Munkoyo and Chibwantu not alienating completely from a possibility of providing probiotic bacteria. This qualifies the potential of Munkoyo and Chibwantu to provide probiotics. However, a further study of Munkoyo and Chibwantu to isolate specific strains of probiotic potential, health benefits in the gut microbiota and possibly produce a starter culture is needed.

Munkoyo and Chibwantu as Galactogogues

Galactogogues are synthetic or plant molecules used to induce, maintain and increase milk production both in human clinical condition and production of milk in the animal dairy industry [30]. Mothers that often have inadequate quantity of breast milk attempt to take foods or herbs (galactogogues) that initiates complex physical and physiological processes including oxytocin and prolactin hormones responsible for lactation [31]. Notable causes of insufficient lactation include increasing rates of obesity, delayed age at childbearing and high rates of cesarean section, [32]. Common herbs and foods used as galactogogues include almond, anise, asparagus caraway, chaste tree and tamarind. Pharmaceutical and herbal galactogogues are increasingly becoming useful but guidance on their use is not available due to insufficient evidence to fit in pharmacological description of galactogogues.

Apart from using Munkoyo and Chibwantu as energy drinks, they are also commonly administered as galactogogues to women experiencing difficulties to produce breast milk for newly born babies in rural communities unable to afford conventional medication.

Munkoyo and Chibwantu beverages reported to be used as galactogogues are a good substitute to herbal galactogogues. However, chemical composition and mechanisms of Munkoyo and Chibwantu as galactogogues need to be well understood to ascertain their pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Thus, further research is needed to determine mechanisms, therapeutic ranges, dosage and possible other effects in breast feeding mothers to qualify Munkoyo and Chibwantu as galactogogues.

Health Benefits of Munkoyo and Chibwantu

Milk fermented products like cheese and yogurt are recommended to provide health benefits because of the presence of LAB. However, lactose intolerance individuals still face a challenge to take fermented milk products. Munkoyo and Chibwantu fermented by similar LAB are another alternative for lactose intolerant individuals. On the other hand, the use of sorghum and millet in the production of Munkoyo provide yet another health benefits to the beverage. Research on sorghum has revealed that the phytochemicals found in sorghum have health benefits ranging from antibacterial to antioxidants, properties including ability to lower hypertension [33,34]. Sorghum is also very beneficial to people suffering from celiac disease, diabetes, obesity and gluten intolerance [35,36]. Several other possible health benefits have been realized from different sorghum genotypes that have already been developped by the sorghum and millet improvement program in Zambia, [37]. Metabolites found in sorghum have the natural capacity to preserve foods and beneficial organisms in the intestines with anti-cancer properties [38]. There is no doubt that Munkoyo and Chibwantu processed from Sorghum as raw material can provide a lot more health benefits to the consumers.

Medicinal Application of Rhynchosia roots

Plant species are extensively used to treat various kinds of diseases such as bacterial infections, cardiovascular, diabetes, digestive, kidney, mental, nervous, nutritional, respiratory, reproductive, sensory, skin infections and several wounds [39]. One of the plants extensively studied for health benefits is Moringa. Moringa Oleifera Lam is cultivated all over the world due to its multiple uses for nutritional and health benefits. This is because Moringa is a very good source of protein, vitamins, oils, fatty acids micro-macro mineral elements, phenolics, anti- flammatory, anti-microbial, antioxidants, anti-cancer, cardiovascular- hyper protective, anti alcer and anti helmintic [40].

Similarly, Rhynchosia root is reported to be used for health benefits apart from an ingredient for processing Munkoyo and Chibwantu. Yellow Rhynchosia roots soaked in water for at least 24 hours produce deep yellow extract that contains a lot of Flavanoids, [41]. The Rhynchosia extract is reported to be used to cure yellow fever, eyes and as contraceptives in women possibly because of anti-inflammatory activity of Flavonoids [42]. Further, isolated compounds of Rhynchosia genus and their plant extract exhibit biological activities that fall under antioxidants, anti-inflammatory, antimycobacterial and antiproliferative [43-48]. With reference to the phytochemicals in Rhynchosia roots, there is need to further investigate the species of Rhynchosia roots used in the processing of Munkoyo and Chibwantu for their medicinal application [49-51].

Conclusion

The purpose of this review is to provide information crucial to health benefits of fermented beverages (Munkoyo and Chibwantu) by providing probiotics, galactogogues and other medicinal application of Rhynchosia roots. Munkoyo and Chibwantu traditionally processed from underutilized cereals like sorghum and millet can provide health energy drink but also supplement herbal galactogogues to mothers experiencing difficulties in breastfeeding who cannot afford conventional medication. Diverse microorganisms spontaneously fermenting Munkoyo and Chibwantu are potentially probiotics that can improve the GIT health. Rhynchosia root extract contains phytochemicals already traditionally prescribed as medicine to cure yellow fever, diarrhea, eyes, wounds and other ailments. Thus, a need for a comprehensive study on Rhynchosia roots, collaborative research on probiotics, galactogogues, nutrition and health benefits of Munkoyo and Chibwantu. Research on galactogogues in particular can also aspire applications in animal dairy (milk) production. Other perceived benefits of phytochemicals in Rhynchosia roots could be in the development of poultry stock-feed with antibiotic properties that can reduce the use of antibiotics in food stuffs which has caused problems of antibiotic resistance worldwide.

References

- Phiri S, Schoustra SE, Heuvel J, Smid E, Shindano J, et al. (2019) Fermented cereal-based Munkoyo beverage: Processing practices, microbial diversity and aroma compounds.PloS one 14:

- Kingamkono R, Sjögren E, Svanberg U (1999) Enteropathogenic bacteria in faecal swabs of young children fed on lactic acid-fermented cereal gruels. Epidemiology and Infection122: 23-32.

- Bintsis T (2018) Lactic acid bacteria as starter cultures: An update in their metabolism and genetics. AIMS microbiology 4:

- De Filippis F, Pasolli E, Ercolini D (2020) The food-gut axis: Lactic acid bacteria and their link to food, the gut microbiome and human health. FEMS microbiology reviews 44: 454-489.

- Oerlemans MM, Akkerman R, Ferrari M, Walvoort MT (2021) Benefits of bacteria-derived exopolysaccharides on gastrointestinal microbiota, immunity and health.Journal of Functional Foods

- Mishra HN, Vasudha S (2013) Non-dairy probiotic beverages.International Food Research Journal 20: 7-15.

- Ou Y, Chen S, Ren F, Zhang M, Ge S, et al. (2019) Lactobacillus casei strain shirots alleviates constipation in Adults by increasing the Pipecolin Acid levels in the Gut.Frontiers in Microbiology 10: 324.

- Zulu R, Ingham L, Harborne B, Eagles J (1994) Flavonoids from the roots of two Rhynchosia species used in the preparation of a Zambian beverage. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 65: 347-354.

- Coronado-Aceves EW, Gigliarelli G, Garibay-Escobar A, Zepeda RER, Curini M (2017) New Isoflavanoids from the extract of Rhynchosia precatorial and their antimycobacterial activity. Journal of Ethnopharcology206: 92-100.

- Nyanzi R, Jooste PJ (2012) Cereal-based functional foods.Probiotics 161-197.

- Nwachukwu E, Achi OK, Ojeoma O (2010) Lactic acid bacteria in fermentation of cereals for the production of indigenous Nigerian foods. African Journal of Food science and Technology 1: 21-26.

- Caplice E, Fitzgerald FG (1999) Food fermentations: Role of microorganisms in food production and preservation. International Journal of Food Microbiology 50: 131-149.

- Foma R, Destain J, Kayisu K, Thonart P (2013) Munkoyo : Des racines comme sources potentielles en enzymes amylolytiques et une boisson fermentée traditionnelle (synthèse bibliographique). Biotechnologie, Agronomie, Societe at Environment17: 352-363.

- Pauwels L, Mulkay P, Ngoy K, Delaude C (1992) Eminia, Rhynchosia et Vigna (Fabacées) à? complexes amylolytiques employés dans la région Zambésienne pour la fabrication de la bière 'Munkoyo'. Belgian Journal of Botany 125: 41-60.

- Zulu R, Grayer JR, Ingham L, Harborne B, Eagles J (1994) Flavonoids from the roots of two Rhynchosia species used in the preparation of a Zambian beverage. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 65: 347-354.

- Wang S, Copeland L (2015) Effect of acid hydrolysis on starch structure and functionality. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition 55: 1081-1097.

- Gadaga TH, Mutukumira AN, Narvhus JA, Feresu SB (1999) A review of Traditional fermented foods and beverages of Zimbabwe. International Journal of Food Microbiology 53: 1-11.

- Blandino A, Al-Aseeri M, pandiella S, Cantero D, Webb C (2003) Cereal-based fermented foods and beverages.Food research international 36: 527-543.

- Nwachukwu E, Achi OK, ojeoma O (2010) Lactic acid bacteria in fermentation of cereals for the production of indigenous Nigerian foods. African Journal of Food science and Technology.

- Rakhmanova A, Khan ZA, shah K (2018) A mini review fermentation and preservation: Role of lactic bacteria.Food Processing and Technology.

- Chavan SK (1989) Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition.Food Science 28: 348-400.

- FAO/WHO (2002) Report on Joint FAO/WHO working group guidelines for evaluation of probiotics in Food.

- Bathala VSK, Venkata S, Vijayendra N, Vijaya O (2015) Trends in diary and non-diary probiotics. Journal of Food Science and Technology.

- Charalampoulos D, Pandiella S, Webb C (2003) Growth studies of potentially probiotic lactic acid bacteria in Cereal-based Substrates. Journal of Applied Microbiology92: 851-859.

- Enujiugha VN (2006) Supplementation of Ogi, Maize -based infant waning food with African oil bean seed – (Pantaclethra Macrophylla Benth). International journal of postharvest technology and innovation.

- Adebolu T, Ihunweze B, onifade A (2011) Antibacterial activity of microorganisms isolated from the liquour of fermented maize ogi on selected diarrhoeal bacteria.Journal of medicine and medical sciences 3: 371-374.

- Mugula J, Nnko SAM, Narvhus JA, Sorhaug T (2003) Microbiological and fermentation characteristics of togwa, a Tanzanian fermented food.International Journal of food microbiology 80: 187-199.

- Schoustra SE, Kasase C, Toarta C, Kassen R, Poulain AJ (2013) Microbial Community Structure of Three Traditional Zambian Fermented Products: Mabisi, Chibwantu and Munkoyo. PloS one 8:

- Phiri S, Souchastra SE, van den heuvel J, Smid EJ, Shindano J, et al. (2020) How processing methods affect the microbial community composition in cereal-based fermented beverage. LWT128: 109451.

- Felipe T, Jaramillo JB, Ruiz-Cortes ZT (2014) Pharmacological overview of Galactogogues. Veterinary Medicine International.

- Rosalle E (2015) Milking the information: Resources on herbal lactation aids. Journal of Consumer Health on the Internet 19: 93-99.

- Bazzano AN, Hofer R, Thebeau S, Gillispie V, Jacabs M (2016) A review of herbal and pharceutical galactogoes for breast feeding.The Oschsner journal 16: 511-524.

- Awika JM, Rooney LW, Waniska RD (2005) Anthocyanins from black sorghum and their antioxidant properties. Food Chemistry90: 293-301.

- Kil HY, Seong ES, Ghimire BK, Chung M, Kwon S, et al. (2009) Antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of crude sorghum extract.Food Chemistry 115: 1234-1239.

- Pasha I, Riaz A, Saeed M, Randhawa A (2015) Exploring the antioxidant perspective of sorghum and millet. Journal of food processing and preservation39: 1089-1097.

- Xiong Y, Zhang P, Warner D, FANG Z (2019) Sorghum grain: From genotype, nutrition and phenolic profile to its health benefits and food applications. Comprehensive reviews in food science and food safety.

- Mbulwe L, Ajayi OC (2020) Case Study-Sorghum Improvement in Zambia: Promotion of Sorghum Open Pollinated Varieties (SOPVs).European Journal of Agriculture and Food Sciences 2: 5.

- Chhikara N, Burale A, Munezero C, Kaur R, Singh G, et al. (2019) Exploring the nutritional and phytochemical potential of sorghum in food processing for food security. Nutrition & Food Science 49: 2.

- Safowora AOE, Onayade A (2013) The role and place of Medicinal Plants in the strategies for disease prevention. African traditional complement Alternative Medicine. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med 10:210-229.

- Farooq ASL, Muhammad A, Anwaral HG (2007) Moringa Oleifera: A food plant with multiple medicinal use. National library of Medicine. Phytother Research21: 17-21.

- Zulu R, DM, Owens D (1997) Munkoyo beverage, a traditional Zambian fermented maize gruel using Rhynchosia root as amylase source. International Journal of Food Microbiology34: 249-258.

- Xeujing J, Zhang C, Jiaolin B, Kai W, Yanbei T, et al. (2020) Flanoids from Rhynchosia Minima root exerts anti-inflammatory activity in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells via MAPK/NF.kB signaling pathway. Inflammopharmacology 28: 289-297.

- Carla M, CEM, Gigliarelli G, Garibay A, Vergura S, et al. (2017) New Isoflavanoids from the extract of Rhynchosia precatorial and their antimycobacterial activity. Journal of Ethnopharcology206: 92-100.

- Caplice E, Fitzgerald G (1999) Food fermentations: Role of microorganisms in food production and preservation. International Journal of Food Microbiolog50: 131-149.

- Chavan SK (1989) Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition.Food Science 28: 348-400.

- foma RDJ, Kayisu K, Thonart P (2013) Munkoyo: Des racines comme sources potentielles en enzymes amylolytiques et une boisson fermentée traditionnelle (synthèsebibliographique). Biotechnologie, Agronomie, Societe at Environment 17:352-363.

- Svahn M, Vasudha S (2013) Non-dairy probiotic beverages.International Food Research Journal 20: 7-15.

- nyanzi R, Jooste PJ (2012) Cereal-based functional foods.Probiotics 161-197.

- Oerlemans MM, Akkerman R, Ferrari M, Walvoort MT (2021) Benefits of bacteria-derived exopolysaccharides on gastrointestinal microbiota, immunity and health.Journal of Functional Food 104289.

- schoustra SKC, Toarta C, Kassen R, Poulain A (2013) Microbial Community Structure of Three Traditional Zambian Fermented Products: Mabisi, Chibwantu and Munkoyo.PloS one 8: e63948.

- Yangwenshan OSC, Frazheng R, Ming Z, Shaoyang G, Huiyan G, et al. (2019) Lactobacillus casei strain shirots alleviates constipation in Adults by increasing the Pipecolin Acid levels in the Gut.Frontiers in Microbiology 10: 324.

Citation: Phiri S, Kasase C, Miyoba N, Ng’ona E, Mbulwe L (2022) A Review of Health Benefits of Fermented Munkoyo, Chibwantu Beverages And Medicinal Application of Rhynchosia Roots. J Food Sci Nutr 8: 148.

Copyright: © 2022 Sydney Phiri, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.