Experiences of Married Men with HIV during the Early Phase of Diagnosis within the Context of Mandatory Disclosure: A Literature Review

*Corresponding Author(s):

Jonathan Peter EeDepartment Of Clinical Psychology, James Cook University, Singapore

Tel:+65 97129747,

Email:yaohongjonathanpeter.ee@my.jcu.edu.au

Abstract

Individuals living with HIV often reveal their diagnosis to someone at some point in their life. This review examines factors that affect disclosure in different countries and the impact of disclosure on relationships and individual’s well-being. In addition, some countries have required individuals to disclose their diagnosis to their spouse or sexual partners during the initial stages of diagnosis or prior to engaging in sexual behaviour. Research studies involving countries with mandatory disclosure laws are discussed to examine their influences on individuals with HIV and whether the laws are effective in promoting safe sex behaviours. Lastly, implications of using the specific model of disclosure theory to examine the role of the mandatory disclosure as a mediating process in affecting the disclosure outcomes and areas of future research are proposed.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

There were many studies that explored different variables influencing HIV disclosure patterns, possible outcomes or consequences of HIV disclosure, such as changes in relationships with their family members and factors that could facilitate or hinder the disclosure process (e.g., stigma) [4,5]. Despite the prevalence of HIV-related research studies focusing on the disclosure behavioural patterns, few research studies explored the impact of mandatory disclosure on individuals’ level of adjustment towards their diagnosis and how they continue to move forward with their life after disclosing to their spouse. The review will cover the concept of disclosure in healthcare (e.g., terminal illness, HIV), theoretical perspectives of HIV disclosure, factors affecting disclosure and the impact of disclosure. In addition, this review will evaluate research findings related to HIV-specific disclosure laws in different countries and discuss the impact of these laws for individuals with HIV on the disclosure process.

DISCLOSURE OF ILLNESS

Sometimes, it can be a difficult process for individuals to disclose to their loved ones and family members after being informed of their diagnosis of terminal illness (e.g., cancer). Individuals sometimes lacked appropriate communication skills to inform their family and loved ones or experienced feelings of uncertainty because they feared receiving negative perception and possible rejection from others after disclosing to them [6]. Most individuals disclosed their terminal illnesses as means of receiving support and help from others while at the same time tried to regain a sense of self-esteem and control over their unfavourable circumstances. Kurowecki and Fergus found that women with breast cancer disclosed their diagnosis to their partners when they were in a newly committed relationship or during the dating process [7]. In doing so, the women were slowly reclaiming their sense of self and bodily esteem as well as evaluating the reaction of their partners towards their diagnosis before deciding whether to proceed further with the relationship further.

Sometimes, individuals disclosed their illnesses unwillingly in unfavourable circumstances for example, disclosing to their potential employers when applying for a new job. In addition, some individuals avoided disclosing to their colleagues because they did not want over preferential treatment or experience stigma from others. This was supported by the findings of the study conducted by Brohan et al., in which participants believed that the employers’ lack of knowledge and awareness of mental health illness often led to negative outcomes such as being rejected for the job which could impact on their level of confidence [8]. Similarly, participants described feeling undermined in their work and viewed their diagnosis as a negative label that influenced their colleagues to have a negative perception towards them. Hence, employees often disclosed their mental health illnesses once they established level of trust with their employers and became competent in their work.

The similarities in the disclosure patterns between individuals with terminal physical and mental illnesses were that they mostly disclosed to their family members to receive family support and help from their family members in managing their condition. In addition, most individuals with terminal physical and mental illnesses might likely experience feelings of uncertainty and doubt about the reactions from others after disclosure. A main difference between the different groups of individuals was that individuals with mental health illnesses might likely view their illnesses as a societal stigma, hence perceived possible negative outcomes of disclosure, for example being rejected and ostracized by others. Individuals who chose not to disclose likely feared the societal stigma of their illnesses and perceived their disclosure experiences would bring about unfavourable outcomes. These reasons will be further explored in the subsequent sections with regards to the diagnosis of HIV, a terminal physical illness with societal stigma, having a possible impact on the disclosure process.

DISCLOSURE OF HIV DIAGNOSIS

THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVE OF HIV DISCLOSURE

Disclosure process model

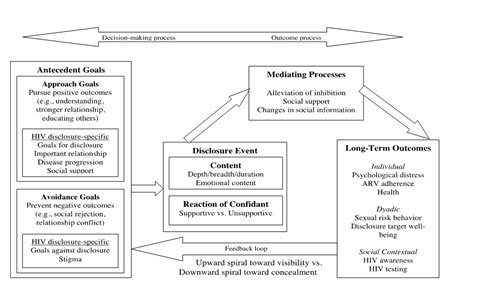

Chaudoir et al., developed the Disclosure Process Model (DPM) that incorporated the different elements of previous theoretical models [15]. The model attempts to accurately capture the complexity of self-disclosure for individuals living with HIV/AIDS and how these individuals evaluate the outcomes of the disclosure process that may influence subsequent future disclosures to others. It comprises three main components namely, decision-making, the disclosure event and its mediating process and long-term outcomes. For the decision-making process, it is further broken down into two types of goals. Approach-focused goals promote the disclosure process (e.g., seeking support and understanding from family, improved relationship with family members and providing educational awareness about HIV/AIDS to others) while avoidance-focused goals promote concealment (e.g., perceived HIV stigma, fear of rejection and breakdown of relationship). These goals could be influenced by the societal norms and behaviour, culture and the severity of the illness. It is also noted that this theoretical model contends that there is a feedback loop that allows the individuals to evaluate their own experiences of the disclosure process and decide whether to repeat the process of disclosing to others or instead conceal their diagnosis from others (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Disclosure Process Model for HIV disclosure. Adapted from Chaudoir et al., [15].

Although this model provides the most detailed and comprehensive understanding of the disclosure process, few research studies have been done involving this model as compared to the consequences theory due to its recent development. A qualitative study consisted of 21 Haitian immigrants in New York were asked about their disclosure experiences in the United States and Haiti [16]. Results of the interview data found that participants had experienced both positive and negative outcomes such as social support, emotional relief, isolation and stigma. Results also indicated that the close relationship with someone whom they trusted is a mediating process to facilitate disclosure which was found to be consistent with the conceptual framework of DPM.

Factors affecting HIV disclosure process

Inclusion criteria for the identification of appropriate research articles were stated as (1) those that were published in English; (2) those that had a specific focus on disclosure experiences and outcomes across different populations and countries. Most of the research findings were summarized into these three main factors namely gender, culture and stigma. Gender and culture were further divided into sub-themes which would be discussed further in later sections.

Gender

Gender differences in disclosure between men and women

These findings were consistent with another research study conducted in Uganda in which most respondents endorsed receiving social support from others and close relationships as the most important reasons for disclosure of HIV serostatus [18]. Most importantly, it was found that respondents indicated that having to explain obvious changes in physical appearances was also a reason for disclosure. Therefore, there are similar themes of fears of partner’s reaction and negative consequences and the progression of the disease that have found to influence the disclosure process. These themes support the evidence of disease progression and consequences theoretical concepts in which both males and females have different factors that affect their decision-making process before they decide to disclose to their spouse. Moreover, it is a peer behavioural norm in African countries for both males and females to disclose their HIV serostatus to each other that might account for the high disclosure rate. Also, having some common reasons, such as seeking support and common behavioural practices, could influence both genders to disclose as explained by the social influence theory.

Self-efficacy and disclosure between men and women

Other recent research in Hawaii showed consistent findings that perceived self-efficacy in decision-making was associated with disclosure in men and women [22]. However, there was a difference in the safe sex self-efficacy as men who disclosed were more likely to engage in safer sex practice than men who declined to disclose. Likewise et al., found similar results that participants who did not disclose had a strong likelihood of not using condoms to reduce HIV transmission [23]. Both self-efficacy for HIV disclosure and safe sex behaviours are related to non-disclosure as individuals with HIV might less likely willing to engage in safe sex practices with their spouses or partners because they feared of being found out and receiving negative reaction from them. Hence, the consequences theory likely provide the best explanation of individuals who perceived themselves having less confidence to disclose their diagnosis are more likely to selective attend to the negative outcomes of disclosure. This may have a societal implication because it can potentially highlight the worrying trend that disclosure is often avoided and not discussed between spouses and sexual partners, while people continue to engage in unsafe sex and increase the rate of transmission.

Relationships and disclosure between men and women

These findings were similar to research conducted in Kenya that showed married women or women in stable long-term relationship and had awareness of their partner’s serostatus were more likely to disclose [26,27]. Besides understanding the relationship as a factor that affected the disclosure process, the researchers also conducted a qualitative study to explore the disclosure event. Participants reported disclosing their diagnosis as a result of declining health and men disclosed to their spouse directly when they were no longer able to conceal their symptoms. On the other hand, women mainly used indirect disclosure techniques, such as placing HIV-related pamphlets and medication around to serve as an entry point into discussing and disclosing their positive serostatus. Positive motivators, such as reducing risk of transmission and accessing early treatment, were found to facilitate positive behavioural outcomes, such as increased condom use or increased concern or kindness by partner. Barriers, such as fear of abandonment, being blamed for acquiring HIV and stigma, were likely to contribute towards negative outcomes, such as separation and conflicts with partners. The strength of both research studies was that different techniques of disclosure were explored and the reasons behind the preference of one disclosure technique over another were also explored between men and women. The limitation of these studies was that only one member of the couples was interviewed and thus the researchers were unable to validate the reported responses or actions of the partner.

Findings of research studies also indicated that some participants required healthcare professionals or friends to assist in the disclosure because they were afraid of the reactions from their partners or less confident about their communication skills. This technique was most useful in cases when the individuals predicted a high risk of negative outcomes or needed additional resources and support for them to work towards the acceptance of their diagnosis. Chen et al., interviewed 29 participants from China to explore the role and types of support that healthcare professionals provided and their impact on the individuals with HIV [28]. Qualitative findings showed that participants had highly favourable impressions of their healthcare professionals and trusted them in the management and disclosure of their condition. In addition, the researchers found that the relationship between the individuals with HIV and their healthcare professionals had a significant impact on their positive outcomes and promoted disclosure to their family members. Similarly, Rujumba et al., found that most HIV-positive women requested healthcare professionals’ expertise and support in disclosure and felt that counseling should be provided to promote disclosure [29].

Although, the Disclosure Process Model was not used as the theoretical model to explain disclosure behavioural patterns for these research studies, findings of these studies indicated support and could be used to explain how the disclosure event could influence the positive and negative outcomes in this research. Meditating processes, such as the involvement of healthcare professionals and a supportive intimate partner, could have a role in facilitating positive long-term outcomes or reduce the barriers to disclosure.

Experiences of disclosure in women

Sexual orientation and disclosure in men

Another study conducted by Bird et al., used measures of sexual behaviour to explore any significant association with disclosure rates in African-American and White males [34]. Results of this study indicated that African-American males were less likely to disclose than Whites, however those who disclosed were reported less likely to engage in unprotected sex. These results might likely indicate that African-American gay men were perhaps more likely to experience HIV-related stigma and chose not to disclose to their sexual partners. Findings of this study were also consistent with a qualitative study, using grounded theory approach, conducted in London with African participants, which showed themes indicating how this group of participants juggled with the dilemmas of disclosure and its impact on their social and intimate relationship (e.g., fear of isolation from friends and family members) [35]. Hence, these research studies showed that although there were slight differences in factors that affected disclosure in gay men, disclosure remains a difficult and challenging process regardless of gender or sexual orientation.

Experiences of disclosure in men

Similar research findings showed that men with a higher severity of HIV/AIDS symptoms were more likely to disclose to their mothers after they were unable to conceal the symptoms [37]. Also, highly educated men were found less likely to disclose, which indicated possible higher levels of coping skills and an unwillingness to worry their family members. Therefore, these research findings indicated that men were neither willing to undergo testing nor disclose to their family unless their disease progressed till it became difficult to conceal their symptom, hence supported the disease progression theory. Despite this, there was another probable explanation as findings of these two research studies also indicated that men weighed the perceived benefits (e.g., need for support) and costs (e.g., HIV-related stigma) before deciding to disclose, thus providing some evidence for the consequence theory as well. Although these research studies showed mostly negative outcomes, there was some evidence of positive outcomes (e.g., familial support and safe sex behaviours) following disclosure. While both research studies had only a small number of participants, these results were consistent with the current literature that disclosure might contribute towards negative outcomes, leading men to perceive disclosure as a threat towards their social and family role, hence deterring men from telling their family members as a way of protecting them.

Culture

Target of disclosure

However, research conducted in Asian countries with collectivistic cultures showed differing findings. In collectivistic cultures, individuals are more likely to emphasize interdependent relationships to their ingroups (e.g., their family members) and aligned their personal goals to meet the goals of the ingroup as compared to individuals in individualistic cultures [43]. Chandra et al., carried out a quantitative study with South Indian participants to explore factors affecting disclosure and found that majority of the participants chose to disclose to their family members (e.g., parents and siblings) and only a small minority (7.5%) disclosed to friends [44]. Another qualitative research conducted in China by Li et al., with interviews of 30 individuals with HIV found that the disclosure process was a family matter within individuals who either experienced involuntary disclosure in which their family members (e.g., parents and siblings) were informed of the diagnosis first before telling the individuals of their diagnosis or voluntary disclosure process in which the individuals typically chose to inform their siblings and parents instead of their spouse [45]. This was further corroborated with a follow-up research study in China using a sample of healthcare professionals who felt that family members, excluding their spouse, should be notified of the diagnosis first before informing the infected individual because it benefitted the individual to cope with themselves better after receiving his or her test result [46].

Researchers of these studies indicated that individuals in collectivist cultures with strong beliefs in family values were more likely accepting of their family being informed because they rarely made decisions without the involvement of their family and often shared their experiences with them [47]. This was further supported by Chen et al., in which they emphasized the differences between Western and Chinese values in which individualism and privacy were held with lower priority over family beliefs and values [28]. Although these research studies did not explore the use of disclosure theories, the use of the social influence theory offered the most likely plausible explanation or framework model that determined how different cultures and societal influences played an important role for individuals with HIV to decide whom they wished to disclose.

Likewise, the involvement of family in supporting individuals with HIV after disclosure was explored in a qualitative research conducted by Lim in which he explored the lived experiences of four HIV-infected men in Singapore [48]. He found that all of them had difficulties adjusting after acquiring a new social identity of a person with HIV and experienced intense feelings, uncertainty and dilemmas that impacted on their relationship with their family, friends and colleagues. Three of the men in the study received positive outcomes of strong family support after disclosure which helped them to face the health challenges, while one man received negative outcomes of strained relationship with family following disclosure which contributed to his low confidence and little willingness to fight the disease. Although the research study had only a small number of participants, it offered a detailed insight into the lived experiences of individuals with HIV in Singapore and how the involvement of support from family could contribute towards the individuals to experience hope and determination in leading their life as a person with HIV.

Modes of transmission

Another quantitative research conducted in Russia with men and women showed that the majority of men who identified intravenous drug use as their mode of HIV transmission were more likely to avoid disclosure and less likely to receive medical treatment [50]. This result could also be attributed to selection biases in the recruitment of participants for the study because active drug users in Russia were excluded from receiving medical treatment for HIV and hence saw little benefits to disclose their diagnosis. Despite these selection biases in their results, both Ko et al., and Davidson et al., research findings highlighted that individuals who acquired HIV through drug use were most likely unwilling to disclose [49,50]. However, the possible reasons behind these findings were unknown and a possible explanation could be that HIV diagnosis was perceived as socially unacceptable and regarded as a punishment for promiscuous sexual behaviour and illegal drug use. However, more research in this area is needed to explore in detail the disclosure patterns among individuals with different modes of HIV transmission and comparison of countries with different drug laws.

HIV STIGMA

Despite the high prevalence of stigma towards HIV in many countries, some individuals were still willing to disclose their diagnosis to others and experience some positive benefits as a result. Paxton conducted a qualitative study in Australia with 49 participants from diverse nationalities and cultures who felt shameful, loss and a sense of worthlessness after diagnosis and before disclosure [55]. As such, they became fearful and guarded in order to prevent the secret of their HIV serostatus from unintentionally disclosed and experience negative repercussions. However, participants found that with time passed by, they decided to disclose publicly to small groups of people and sometimes to the media, despite the presence of stigma and felt a sense of relief after revealing their burden of the secret. In addition, most of them developed new meaning of their lives (e.g., having a sense of purpose) and created a new identity of becoming a spokesperson to create awareness and understanding of HIV which gained greater acceptance from their community. Similarly, Mfecane found that married men with HIV in South African experienced positive reactions when they disclosed their serostatus despite their initial perceived negative fears of discrimination and stigmatization from their community [56].

Despite receiving negative outcomes after disclosure to others, such as experiencing rejection from others due to stigma, heterosexual women and gay men experienced few regrets after disclosure because it facilitated them coming to terms with their diagnosis and improved their level of coping and well-being [57,58]. In fact, Holt et al., found that most individuals used disclosure as way of coping and often repeated the process to disclose to other individuals to facilitate self-acceptance of their condition [59]. This research evidence provided support for the Disclosure Process Model because it highlighted the biofeedback loop whereby individuals evaluated the disclosure process and developed effective coping strategies to facilitate positive outcomes the next time they disclosed.

MANDATORY HIV DISCLOSURE LAWS

Due to increasing rates of HIV transmission, some countries have introduced laws requiring HIV-positive individuals to disclose their diagnosis to their spouse or sexual partners. For example, 24 US states enacted HIV-specific laws that made disclosure compulsory for an HIV-infected person to inform their diagnosis to their sexual partner before engaging in sexual activity [60]. Penalties for breaking these laws ranged from a $2500 fine or less than 12 months to up to 30 years in jail depending on the severity and intent of the crime. Most research on HIV mandatory disclosure laws focused on three main areas: 1) whether individuals with HIV were aware or understand the law; 2) impact of criminalization on the lives of individuals with HIV; 3) effectiveness of the law (e.g., in reducing rate of sexual transmission) which will be discussed further in this section. In addition, this section will discuss the impact of the period between diagnosis and disclosure on individuals with HIV and lastly, explore implications of mandatory law on the theoretical processes of disclosure.

AWARENESS OF THE LAW

On the other hand in England and Wales, research findings found that gay men were sometimes confused and misunderstood the disclosure laws [62]. In addition, almost half of them reported that the possibility of being prosecuted for non-disclosure was not likely to change their sexual behaviours and became less willing to disclose their HIV serostatus. Therefore, most individuals with HIV often avoid disclosing their serostatus despite having awareness of the mandatory disclosure law and use strategies (e.g., avoiding sexual intimacy) to ensure that their positive serostatus remain a secret.

IMPACT OF CRIMINALIZATION

EFFECTIVENESS OF THE LAW

Meanwhile, O’Byrne also conducted modeling analysis with the current research studies and arrived at similar findings that although the mandatory disclosure laws might prevent the risk of HIV transmission in small isolated cases, there was little overall impact that the laws could significantly reduce the HIV transmission on a population level [67]. Instead, there was some evidence that the use of mandatory disclosure laws could likely exacerbated the spread of HIV transmission because people were less likely to receive HIV testing and remained unaware of their suspected HIV diagnosis. Therefore, the implication of this study showed that HIV mandatory disclosure law might not promote the societal context of encouraging safer sex and regular HIV testing and instead reinforced the societal stigma and rejection of the individuals with HIV. This was further explained by Galletly et al., who argued that there was no significant evidence that disclosure was effective as a preventive strategy to reduce HIV transmission through condom use [68]. Instead, the disclosure law undermined efforts to reinforce the use of condom as a societal and behavioural norm and instead promoted HIV stigma and fear. Hence, there is insufficient evidence to conclude that the use of mandatory HIV disclosure law is an effective strategy to reduce sexual transmission and infection rates.

LENGTH OF TIME BETWEEN DIAGNOSIS AND DISCLOSURE

Other research studies showed that gay men, who knew their diagnosis for at least one year, had a higher likelihood of disclosing as compared to those who had a short time period between diagnosis and disclosure diagnosis [71]. Paxton found that heterosexual individuals rarely informed others immediately after diagnosis and often needed time to come to terms through sharing their fears with a counsellor [55]. Findings in her study, which explored the experiences of individuals disclosing their diagnosis to the public, indicated that the average time between diagnosis and public disclosure to other people besides their family members and friends was 2.6 years with females having a shorter time frame (2.0 years) than men (3.4 years). Thus, there are different periods in which individuals with HIV are prepared to inform others of their diagnosis and with individuals being affected by the introduction of HIV-specific disclosure laws, there could likely be a decreased autonomy and sense of control for them in deciding when they are willing and comfortable to inform others. Therefore, it remains unclear whether these laws will facilitate or hinder the psychological processes and creation of a new self-identity after diagnosis in individuals with HIV.

There were mixed nature of findings on the length of time between diagnosis of HIV and HIV disclosure. Most research findings found that an average of seven to a month is a typical time period for the person to disclose their diagnosis to other while a small number of studies found that individuals took about one to two years before they were ready to disclose. It was noted that individuals with HIV diagnosis made the choice on their own in deciding when they were ready to disclose. Often, individuals who had close relationship with the targeted person that they wished to disclose often disclose within a shorter timeframe as compared to others who had a more distance relationship with the targeted person (i.e., a stranger).

IMPLICATIONS OF MANDATORY DISCLOSURE

LIVING WITH HIV FOLLOWING DIAGNOSIS AND DISCLOSURE

FUTURE RESEARCH

Other kinds of research can also explore whether different modes of transmission has had any affect on the disclosure patterns and support that the individuals receive in helping them to fight their disease. Likewise, there are limited research studies that explore the impact of disclosure on individuals receiving the news of diagnosis from their infected sexual partner and the level of support that they provide for their infected spouse or sexual partner which could be explored through semi-structured interviews. A wider scale study, that involves a few countries with varying culture and societal norms across different population, is also recommended to explore in-depth individuals’ preferences for the target disclosure and their reasons behind their choice. Likewise, future studies can also explore the experiences of youths being diagnosed with HIV and how they navigate the disclosure processes with their family members and friends. Other studies can also focus on countries with mandatory disclosure and explore its impact on populations with different sexual orientations and gender so as to understand the possible impact of mandatory disclosure on individuals’ relationships with their family members, spouses or sexual partners. Lastly, a questionnaire or qualitative study can be done to explore the public or society’s perceptions towards mandatory disclosure and their reactions when their friends or family members revealed their diagnosis to them.

CONCLUSION

REFERENCES

- AVERT (2014) Global HIV and AIDS Statistics. AVERT,

- Cusick L (1999) The process of disclosing positive HIV status: findings from qualitative research. Cult Health Sex 1: 3-18.

- Dorrell J, Katz J (2013) “I knew I had something bad because no-one spoke about it” - disclosure discovery: experiences of young people with perinatally acquired HIV in the UK. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies 8: 353-361.

- Derlega VJ, Winstead BA, Greene K, Serovich J, Elwood WN (2002) Perceived HIV-related Stigma and HIV Disclosure to Relationship Partners after Finding Out about the Seropositive Diagnosis. J Health Psychol 7: 415-432.

- Wilson S, Derlega VJ, Woody A, Lewis R, Braitman AL, et al. (2014) Disentangling reactions to HIV disclosure: effects of HIV status, sexual orientation, and disclosure recipients' gender. J Health Psychol 19: 285-295.

- Zamanzadeh V, Rahmani A, Valizadeh L, Ferguson C, Hassankhani H, et al. (2013) The taboo of cancer: the experiences of cancer disclosure by Iranian patients, their family members and physicians. Psychooncology 22: 396-402.

- Kurowecki D, Fergus KD (2014) Wearing my heart on my chest: dating, new relationships, and the reconfiguration of self-esteem after breast cancer. Psychooncology 23: 52-64.

- Brohan E, Evans-Lacko S, Henderson C, Murray J, Slade M, et al. (2014) Disclosure of a mental health problem in the employment context: qualitative study of beliefs and experiences. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 23: 289-300.

- CDC (2010) HIV Among Men in the United States. CDC, Georgia, USA.

- Badcock J (1998) Involving Family and Significant Others in Acute Care. In: Aronstein DM, Thompson BJ (eds.). HIV and Social Work: A Practitioner's Guide. Haworth Press, Pennsylvania, USA. Pg no: 586.

- Kalichman SC (1995) Understanding AIDS: A guide for mental health professionals. Libraries Australia, Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, USA. Pg no: 287-356.

- Serovich JM (2001) A test of two HIV disclosure theories. AIDS Educ Prev 13: 355-364.

- Serovich JM, Esbensen AJ, Mason TL (2005) HIV disclosure by men who have sex with men to immediate family over time. AIDS Patient Care STDS 19: 506-517.

- Zea MC, Reisen CA, Poppen PJ, Bianchi FT, Echeverry JJ (2007) Predictors of disclosure of human immunovirus-positive serostatus among Latino gay men. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol 13: 304-312.

- Chaudoir SR, Fisher JD, Simoni JM (2011) Understanding HIV disclosure: a review and application of the Disclosure Processes Model. Soc Sci Med 72: 1618-1629.

- Conserve DF, King G (2014) An examination of the HIV serostatus disclosure process among Haitian immigrants in New York City. AIDS Care 26: 1270-1274.

- Deribe K, Woldemichael K, Njau BJ, Yakob B, Biadgilign S, et al. (2010) Gender differences regarding barriers and motivators of HIV status disclosure among HIV-positive service users. SAHARA J 7: 30-39.

- Ssali SN, Atuyambe L, Tumwine C, Segujja E, Nekesa N, et al. (2010) Reasons for disclosure of HIV status by people living with HIV/AIDS and in HIV care in Uganda: an exploratory study. AIDS Patient Care STDS 24: 675-681.

- Bandura A, National Inst of Mental Health (1986) Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. American Psychological Association, Englewood Cliffs, Prentice-Hall, New Jersey, USA.

- Bandura A (1997) Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Worth Publishers, Basingstoke, UK. Pg no: 604.

- Kalichman SC, Nachimson D (1999) Self-efficacy and disclosure of HIV-positive serostatus to sex partners. Health Psychol 18: 281-287.

- Sullivan KM (2009) Disclosure of serostatus to sex partners among HIV-positive men and women in Hawaii. Issues Ment Health Nurs 30: 687-701.

- Stein MD, Freedberg KA, Sullivan LM, Savetsky J, Levenson SM, et al. (1998) Sexual ethics. Disclosure of HIV-positive status to partners. Arch Intern Med 158: 253-257.

- King R , Katuntu D , Lifshay J , Packel L , Batamwita R, et al. (2008) Processes and outcomes of HIV serostatus disclosure to sexual partners among people living with HIV in Uganda. AIDS Behav 12: 232-243.

- Derlega VJ, Winstead BA, Greene K, Serovich J, Elwood WN (2004) Reasons for HIV disclosure/nondisclosure in close relationships: testing a model of HIV-disclosure decision making. Journal of social and clinical psychology 23: 747-767.

- Peltzer K, Mlambo G (2013) HIV Disclosure Among HIV Positive New Mothers in South Africa. Journal of Psychology in Africa 23: 327-333.

- Roxby AC, Matemo D, Drake AL, Kinuthia J, John-Stewart GC, et al. (2013) Pregnant women and disclosure to sexual partners after testing HIV-1-seropositive during antenatal care. AIDS Patient Care STDS 27: 33-37.

- Chen WT, Starks H, Shiu CS, Fredriksen-Goldsen K, Simoni J, et al. (2007) Chinese HIV-positive patients and their healthcare providers: contrasting Confucian versus Western notions of secrecy and support. ANS Adv Nurs Sci 30: 329-342.

- Rujumba J, Neema S, Byamugisha R, Tylleskär T, Tumwine JK, et al. (2012) “Telling my husband I have HIV is too heavy to come out of my mouth”: pregnant women's disclosure experiences and support needs following antenatal HIV testing in eastern Uganda. J Int AIDS Soc 15: 17429.

- Rouleau G, Côté J, Cara C (2012) Disclosure experience in a convenience sample of quebec-born women living with HIV: a phenomenological study. BMC womens health 12: 37.

- Chen WT, Shiu CS, Simoni JM, Zhao H, Bao MJ, et al. (2011) In Sickness and in Health: A Qualitative Study of How Chinese Women with HIV Navigate Stigma and Negotiate Disclosure within their Marriages/Partnerships. AIDS Care 23: 120-125.

- Wei C, Lim SH, Guadamuz TE, Koe S (2012) HIV disclosure and sexual transmission behaviors among an Internet sample of HIV-positive men who have sex with men in Asia: implications for prevention with positives. AIDS Behav 16: 1970-1978.

- Yoshioka MR, Schustack A (2001) Disclosure of HIV status: cultural issues of Asian patients. AIDS Patient Care STDS 15: 77-82.

- Bird JD, Fingerhut DD, McKirnan DJ (2011) Ethnic differences in HIV-disclosure and sexual risk. AIDS Care 23: 444-448.

- Paparini S, Doyal L, Anderson J (2008) 'I count myself as being in a different world': African gay and bisexual men living with HIV in London. An exploratory study. AIDS Care 20: 601-605.

- Dageid W, Govender K, Gordon SF (2012) Masculinity and HIV disclosure among heterosexual South African men: implications for HIV/AIDS intervention. Cult Health Sex 14: 925-940.

- Shehan CL, Uphold CR, Bradshaw P, Bender J, Arce N, et al. (2005) To tell or not to tell: Men's disclosure of their HIV-positive status to their mothers. Family Relations 54: 184-196.

- Hays RB, McKusick L, Pollack L, Hilliard R, Hoff C, et al. (1993) Disclosing HIV seropositivity to significant others. AIDS 7: 425-431.

- Guo Y, Li X, Liu Y, Jiang S, Tu X (2014) Disclosure of same-sex behavior by young Chinese migrant men: context and correlates. Psychol Health Med 19: 190-200.

- Ko?rner H (2007) Negotiating cultures: disclosure of HIV-positive status among people from minority ethnic communities in Sydney. Cult Health Sex 9: 137-152.

- Wolitski RJ, Rietmeijer CA, Goldbaum GM, Wilson RM (1998) HIV serostatus disclosure among gay and bisexual men in four American cities: general patterns and relation to sexual practices. AIDS Care 10: 599-610.

- Makin JD, Forsyth BW, Visser MJ, Sikkema KJ, Neufeld S, et al. (2008) Factors affecting disclosure in South African HIV-positive pregnant women. AIDS Patient Care STDS 22: 907-916.

- Han SP, Shavitt S (1994) Persuasion and culture: Advertising appeals in individualistic and collectivistic societies. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 30: 326-350.

- Chandra PS, Deepthivarma S, Manjula V (2003) Disclosure of HIV infection in south India: patterns, reasons and reactions. AIDS Care 15: 207-215.

- Li L, Sun S, Wu Z, Wu S, Lin C, et al. (2007) Disclosure of HIV status is a family matter: field notes from China. J Fam Psychol 21: 307-314.

- Li L, Lin C, Wu Z, Lord L, Wu S (2008) To tell or not to tell: HIV disclosure to family members in China. Dev World Bioeth 8: 235-241.

- Muller JH, Desmond B (1992) Ethical dilemmas in a cross-cultural context. A Chinese example. West J Med 157: 323-327.

- Lim FKG (2004) Life Goes On: Living with HIV and AIDS in Singapore. Asian Journal of Social Science 32: 42-65.

- Ko NY, Lee HC, Hsu ST, Wang WL, Huang MC, et al. (2007) Differences in HIV disclosure by modes of transmission in Taiwanese families. AIDS Care 19: 791-798.

- Davidson AS, Zaller N, Dukhovlinova E, Toussova O, Feller E, et al. (2012) Speaking the truth: an analysis of gender differences in serostatus disclosure practices among HIV-infected patients in St Petersburg, Russia. Int J STD AIDS 23: 685-688.

- Asiedu GB, Myers-Bowman KS (2014) Gender differences in the experiences of HIV/AIDS-related stigma: a qualitative study in Ghana. Health Care Women Int 35: 703-727.

- Lee SJ, Li L, Iamsirithaworn S, Khumtong S (2013) Disclosure challenges among people living with HIV in Thailand. Int J Nurs Pract 19: 374-380.

- Messersmith LJ, Semrau K, Hammett TM, Phong NT, Tung ND, et al. (2013) 'Many people know the law, but also many people violate it': discrimination experienced by people living with HIV/AIDS in Vietnam--results of a national study. Glob Public Health 1: 30-45.

- Skinta MD, Brandrett BD, Schenk WC, Wells G, Dilley JW (2014) Shame, self-acceptance and disclosure in the lives of gay men living with HIV: an interpretative phenomenological analysis approach. Psychol Health 29: 583-597.

- Paxton S (2002) The paradox of public HIV disclosure. AIDS Care 14: 559-567.

- Mfecane S (2012) Narratives of HIV disclosure and masculinity in a South African village. Cult Health Sex 14: 109-121.

- Serovich JM, Mason TL, Bautista D, Toviessi P (2006) Gay men’s report of regret of HIV disclosure to family, friends, and sex partners. AIDS Educ Prev 18: 132-138.

- Serovich JM, McDowell TL, Grafsky EL (2008) Women's report of regret of HIV disclosure to family, friends and sex partners. AIDS Behav 12: 227-231.

- Holt R, Court P, Vedhara K, Nott KH, Holmes J, et al. (1998) The role of disclosure in coping with HIV infection. AIDS Care 10: 49-60.

- Galletly CL, Difranceisco W, Pinkerton SD (2009) HIV-positive persons' awareness and understanding of their state's criminal HIV disclosure law. AIDS Behav 13: 1262-1269.

- Christiansen M, Lalos A, Johansson EE (2008) The Law of Communicable Diseases Act and disclosure to sexual partners among HIV-positive youth. Vulnerable Child Youth Stud 3: 234-242.

- Dodds C, Bourne A, Weait M (2009) Responses to criminal prosecutions for HIV transmission among gay men with HIV in England and Wales. Reprod Health Matters 17: 135-145.

- Adam BD, Elliott R, Corriveau P, English K (2013) Impacts of Criminalization on the Everyday Lives of People Living with HIV in Canada. Sexuality Research and Social Policy 11: 39-49.

- Burris S, Cameron E (2008) The case against criminalization of HIV transmission. Jama 300: 578-581.

- Jürgens R, Cohen J, Cameron E, Burris S, Clayton M (2009) Ten reasons to oppose the criminalization of HIV exposure or transmission. Reprod Health Matters 17: 163-172.

- Simoni JM, Pantalone DW (2004) Secrets and safety in the age of AIDS: does HIV disclosure lead to safer sex? Top HIV Med 12: 109-118.

- O’Byrne P (2011) Criminal Law and Public Health Practice: Are the Canadian HIV Disclosure Laws an Effective HIV Prevention Strategy? Sexuality Research and Social Policy 9: 70-79.

- Galletly CL, Pinkerton SD (2006) Conflicting Messages: How Criminal HIV Disclosure Laws Undermine Public Health Efforts to Control the Spread of HIV. AIDS Behav 10: 451-461.

- Tom P (2013) Knowledge, attitudes and practices of HIV-positive patients regarding disclosure of HIV results at Betesda Clinic in Namibia. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med 5: 409.

- Skunodom N, Linkins RW, Culnane ME, Prymanee J, Kannasoot C, et al. (2006) Factors associated with non-disclosure of HIV infection status of new mothers in Bangkok. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 37: 690-703.

- Batterham P, Rice E, Rotheram-Borus MJ (2005) Predictors of serostatus disclosure to partners among young people living with HIV in the pre- and post-HAART eras. AIDS Behav 9: 281-287.

- Remien RH, Rabkin JG (2001) Psychological aspects of living with HIV disease: a primary care perspective. West J Med 175: 332-335.

- Frain MP, Berven NL, Chan F, Tschopp MK (2008) Family Resiliency, Uncertainty, Optimism, and the Quality of Life of Individuals With HIV/AIDS. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin 52: 16-27.

Citation: Ee JP (2017) Experiences of Married Men with HIV during the Early Phase of Diagnosis within the Context of Mandatory Disclosure: A Literature Review. J AIDS Clin Res Sex Transm Dis 4: 014.

Copyright: © 2017 Jonathan Peter Ee, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.