Profiling and Bioactivity of Apis Mellifera Royal Jelly in Himachal Pradesh

*Corresponding Author(s):

Simran BhatiaDepartment Of Entomology, Dr YS Parmar University Of Horticulture And Forestry, Nauni, Solan, Himachal Pradesh, India

Email:simranuhf@gmail.com

Abstract

This study was conducted to provide insights on the physicochemical properties, antioxidant activity, micronutrient status and antibacterial potential of hive bee (Apis mellifera L.) royal jelly collected in spring, summer and autumn seasons from Himachal Pradesh. The royal jelly was collected from selected 10 royal jelly-yielding stock in 3 seasons (spring, summer and autumn) and analyzed for physicochemical characteristics, mineral status and antibacterial potential using standard methodologies. The apiary royal jelly displayed good to excellent inhibitory activity against Bacillus subtilis (ATCC 6633), whereas, fair to good against Escherichia coli (NCTC 10418) and Staphylococcus aureus (NCTC 3750) at 100 per cent and 50 per cent concentrations in spring, summer and autumn season. The physicochemical properties, including pH, moisture, lipid and protein content, were found to be within standard ranges, signifying good quality and superiority of royal jelly. Antioxidant activity showed its potential as a bioactive substance. Micronutrient analysis revealed the presence of important minerals (Fe, Zn and Mg). pH, moisture content, total soluble solids content showed strong positive correlations. these findings highlight the therapeutic potential of royal jelly as a natural antimicrobial agent, particularly for managing gram-positive and gram-negative bacterial infections. Overall, the results highlight the high quality and multifunctional nature of royal jelly making it a valuable natural product for use in medicine, cosmetics and nutrition. This paper presents a pioneer study on the seasonal variations in physicochemical properties and antibacterial potential of the hive bee (A. mellifera) royal jelly and has not been done in Himachal under the present scenario.

Keywords

Antibacterial; Apis mellifera; Beekeeping; Physicochemical; Royal jelly

Introduction

Honey bees play a vital role in both ecosystems and agriculture as a primary pollinator of crops. Bee products such as honey, venom, pollen, wax, propolis and Royal Jelly (RJ) [1-4], contribute to nutrition, medicine and various industries highlighting the ecological and economic significance of these beneficial insects in sustaining biodiversity and human well-being. The term "Royal Jelly" was coined by the french scientist René Antoine de Réaumur (1683-1757), who associated its consumption with the extraordinary growth of the queen bee [5,6]. In 1852, Reverend Langstroth, considered the father of American beekeeping, conducted the first chemical analysis of royal jelly. Aristotle was the first to discover the potential benefits of royal jelly in bees, attributing increased physical strength and potential improvements in intellectual capacity to its consumption [5]. During the 1950s, Langstroth proposed the commercial use of royal jelly, especially in regions where honey production was not economically viable [7]. The exploration of RJ as a functional product and health enhancer gained momentum in the early 1960s with the development of "Apitherapy." Since then, the unique properties and characteristics of RJ have been extensively studied and applied in therapy for both humans and bees [5]. Royal jelly is the result of hypopharyngeal gland (watery) and mandibular gland (milky) secretion. Such glands are located in the workers heads and royal jelly is produced by 5 to 14 days old workers, called nurse bees [8]. Interestingly, first three days of larval growth, both queen and bee worker larvae are fed on the royal jelly and then the worker bee larvae fed on a combination of royal jelly and food store (pollen and honey) while the queen continues to fed on royal jelly from worker nurse. RJ significantly influences the lifespan, with worker bees living about 45 days, while queen bees can live up to five years, exhibiting prolific egg-laying capabilities, averaging 2000-3000 eggs daily over several years bees [9-11].

Bee products have gained significant attention in both traditional and modern medicine, aligning with the growing health-conscious society [1,4,12,13]. RJ has been produced on a large scale for commercial purposes and its market value is significantly higher than other bee products such as honey or pollen thus it is a major income source for beekeepers [14]. Recently the origin and function of RJ such as Major Royal Jelly Proteins (MRJPs) for the development of the larvae [15], antimicrobial properties [11], medicinal value [1,16], proteins and peptides [17], the potential applications for cancer treatment [18], and health aging and longevity [19], have been reported. In recent years, there has been a growing interest in the application of bee products in traditional and modern medicine leading to numerous studies exploring their health benefits and pharmacological properties. Royal jelly is widely used as a dietary supplement due to its antibacterial [20], antitumor [21], antiallergy, anti-inflammatory, antifatigue [22], immunomodulatory effects and antihypercholesterolemic [23], immunomodulatory [14,15,17,24,25].

These biological effects of royal jelly are attributed to the presence of many active ingredients in RJ such as 10- Hydroxy-2-Decenoic Acid (10-HDA), active peptides such as Major Royal Jelly Proteins (MRJPs), royalactin, steriods, acetyl choline and other compounds which might be of high importance in modern medicine for the development of new drugs [25,26]. RJ is composed of approximately 60-70 per cent water, 1.22 per cent ash content, 3-8 per cent lipids, 9-18 per cent protein, 6-18 per cent carbohydrates, 2-5 per cent 10-HDA, 18-23 per cent total phenolic content, 0.8-30 per cent minerals, and trace amounts of polyphenols and vitamins [9]. This nutrient rich substance serves as the exclusive food for honey bee larvae during the first 72 hours of their larval life and remains a vital source of nourishment for the queen throughout her larval and adult phases. Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, attributed to its fatty acids, such as trans-10-hydroxydec-2-enoic acid and bioactive peptides like jelleines and royalisin. Studies highlight its effectiveness against Bacillus cereus, Enterococcus faecalis, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus [27]. RJ's antibacterial action is mainly linked to its therapeutic fatty acids and peptides, with reported activity against Salmonella, Proteus and B. subtilis etc. This makes RJ a potent natural antibiotic with applications in diets, cosmetics, and pharmacology. RJ contributes to the queen bee's immunity against harmful bacteria, enhancing its role in beekeeping and related industries. The beekeeping community has adopted the grafting process, particularly the Doolittle method of larvae grafting [28], to enhance royal jelly production. Preserving the integrity of royal jelly for human consumption is a crucial consideration, as it is susceptible to changes in its properties. RJ is particularly sensitive to light and heat, and direct exposure to air can lead to oxidation [29-31]. Therefore, careful storage conditions are essential to maintain the stability and quality of RJ intended for human use. This paper explores the physicochemical properties of royal jelly produced by Apis mellifera colonies and the antibacterial activity of royal jelly against common bacterial pathogens in Himachal Pradesh, India.

Materials and Methods

The research was conducted in University Apiary and Apiculture Laboratory of the Department of Entomology, College of Horticulture, Dr YS Parmar University of Horticulture and Forestry, Nauni, Solan, Himachal Pradesh (1245m amsl, 30°51'25''N 77°10'06''E). The selection of A. mellifera colonies for royal jelly production was done on the basis of biological and economic characteristics like colony strength, brood area, prolificness, hygienic behavior, pollen and honey stores. Thirty A. mellifera colonies were screened and marked for experiment at UHF Apiary in experimental farm. Out of these 30 colonies screened, 10 A. mellifera colonies having high biological and economic characteristics were selected for royal jelly production and performance of these colonies was recorded. Standardized measurement protocols were followed to ensure consistency across all parameters.

Sample Collection

Larval grafting was carried out in these selected Apis mellifera colonies for royal jelly production using the Doolittle method [28]. 24-hour-old larvae were grafted into the cups within queen less cell builder colonies. Observations were repeated at 21-day intervals across three seasons during the spring (February-March), summer (April-June) and autumn (August-October) of 2024 with 3 replications per season. Royal jelly was then harvested 72 hours after larval grafting and stored in dark vials at -20°C for physicochemical and antibacterial properties analysis.

Physicochemical Analysis

The physicochemical properties viz., pH, moisture content, ash content, total solid content, carbohydrates, bioactive compounds viz., phenols, flavonoids, DPPH content and micronutrient content was studied for spring, summer and autumn season of 2024 in royal jelly samples collected from these selected high royal jelly producing colonies.

Determination of pH

The pH was determined by dissolving 1g of royal jelly in 7.5ml distilled water and measuring with a pH probe [32].

Determination of Moisture, Solids and Ash Contents

The amounts of ash in each royal jelly sample (each 1g) were measured after being in the oven at 550°C for 8 hours. After 1 hour of losing heat, the crucible was weighted and the difference between initial and final weights indicated the amount of ash present in 1g of royal jelly samples. To calculate the moisture percentage of royal jelly samples, 1g of each specimen was weighed in a crucible to put in an oven of 105°C for 3 hours. The crucible was carefully weighed after cooling. The samples remained in the oven for 1 or more hour to examine if the weights decreased. The process was repeated again until the evaporation of water is complete with constant weight [33]. Total solid content of each royal jelly sample was estimated by using the following formula:

Total solids (%) = 100-Moisture content.

Determination of Lipids

Each sample of royal jelly (1g) was weighted and homogenized with 100mL of distilled water using an ultrasonic homogenizer for 30 minutes until the compound was completely dispersed. In the next step, equal amounts of chloroform and ethanol were added to the mixture and filtered through a Whatman filter paper No. 1 (Sigma Aldrich, USA). Buchner tunnel and vacuum were applied for more rapid performance of filtration. After filtration, the chloroform phase was separated and transferred to a beaker on a warm water bath to evaporate the chloroform. Finally, the beaker was cooled and weighed to calculate the amount of lipid present in 1g of royal jelly [34].

Determination of Proteins

The royal jelly samples protein content was estimated per the methodology given by Lowry et al. [35]. The 0.05g RJ dissolved in 10ml double distilled water and then centrifuged (25min, 2300g). Folin-Ciocalteu reagent was added to the supernatant and the absorbance was measured at 750nm in Spectrophotometer.

Determination of Carbohydrates, Phenols and Flavonoids

Total carbohydrates content of royal jelly was obtained by difference [36], using the formula:

Total carbohydrates (CHO) = 100 - (moisture%+ protein%+ lipids% + ash%).

The royal jelly's total phenolic and flavonoid content were measured by the Folin-Ciocalteu and aluminium chloride methods, respectively [37].

Determination of Antioxidant Potential

The free radical scavenging activity of royal jelly samples was determined by 1,1-Diphenyl-2-Picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) assay [38].

Micronutrient Composition

Micronutrient such as Chromium, Copper, Nickel, Manganese, Iron, Magnesium and Zinc were determined as per the method given by Muresan et al. [39], in atomic absorption spectrophotometer (Motras Scientific).

UHPLC-Based Profiling and Elemental Analysis of Royal Jelly

Standard procedures were followed when conducting the analysis. Protein content (as determined by the SLS/CH/STP-16 method), organic acids and flavonoids (such as caffeine, ferulic acid, gallic acid, apigenin, quercetin, chyrsin, hesperetin, etc.) and vitamins B2 and C were among the parameters examined using UHPLC methods. Additionally, elemental content such as iron, copper, sodium, calcium, magnesium, and potassium was determined using the SLS/CH/STP-02 technique. The analysis was carried out by Shoolini Lifesciences Pvt. Ltd., an Indian institution with NABL accreditation.

Antibacterial Activity Assessment

In this study, the antibacterial activity of royal jelly samples was assessed against three bacterial isolates. The Gram-negative bacterium Escherichia coli (NCTC 10418) and two Gram-positive species, Staphylococcus aureus (NCTC 3750) and Bacillus subtilis (ATCC 6633), were obtained in lyophilized form from the Central Research Institute, Kasauli, Solan. After twenty-four-hour bacterial cultures were inoculated into Nutrient Broth i.e., 5ml each (Merck, Germany) and incubated at 37°C. The antibacterial evaluation was conducted using the agar diffusion well method. A uniform bacterial culture was prepared on Nutrient Agar (Himedia, India) plates by spreading bacterial suspensions with sterile cotton swabs. Wells (each 5mm in diameter) were created in the agar using a sterile micropipette tip. Royal jelly samples (100% and 50% in sterile water) were prepared and 100μL of each dilution was dispensed into the wells. The plates were then incubated at 37°C for 24 hours. Following incubation, the diameter of the inhibition zones was measured in millimeters using a ruler and recorded, as described by Eshraghi et al. [40].

Statistical Analysis

The data recorded was analyzed by using R-software for correlation heatmap construction (library used: ggplot2, agricolae, dplyr, corrplot, ggcorrplot) and MS-Excel All determinations were carried out in triplicate and after calculating the amount of each group of components in three seasons of samples of royal jelly, the amounts were reported as mean ± standard error (SE). P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results And Discussion

The determination of physicochemical properties of royal jelly across the three seasons are displayed in table 1 under following subheadings.

|

Parameter |

Spring |

Summer |

Autumn |

Mean |

p-value |

|

pH |

4.08±0.006 |

4.07±0.003 |

4.10±0.006 |

4.08 |

0.301 |

|

Moisture content (%) |

64.00±0.577 |

64.33±0.667 |

66.67±0.882 |

65.00 |

0.739 |

|

Total solids content (%) |

36.00±0.577 |

35.67±0.667 |

33.33±0.882 |

35.00 |

0.739 |

|

Ash content (%) |

2.00 |

2.12 |

2.01 |

2.04 |

0.000 |

|

Lipids (%) |

7.50±0.577 |

7.50±0.577 |

6.87±0.606 |

7.29 |

0.381 |

|

Protein (%) |

17.12±0.120 |

17.49±0.215 |

16.00±1.299 |

16.87 |

0.036 |

|

Carbohydrates (%) |

9.14±0.00 |

8.77±0.969 |

8.97±0.033 |

8.96 |

0.930 |

|

Phenol (μg/mg) |

20.40±1.442 |

20.67±1.764 |

21.00±1.528 |

20.69 |

0.978 |

|

Flavonoids (μg/mg) |

1.37±0.095 |

1.40±0.088 |

1.36±0.033 |

1.38 |

0.983 |

Table 1: Seasonal differences in the physicochemical properties of royal jelly from Apis mellifera.

Note: ± denotes standard error

pH

The analysis of data on pH revealed no significant difference during the spring (4.08), summer (4.07) and autumn (4.10) seasons (p>0.05) indicating slight seasonal variation. pH is one of the criteria for determining the physical property of RJ, in the light of this statement, Lercker et al. [41], reported that royal jelly is highly acidic with pH ranged between 3.4 - 4.5. Similarly, Isidorov et al. [42], reported 3.95 pH of pure royal jelly which showed an acidic nature of royal jelly. Sereia et al. [43], reported an average range of pH between 3.92-4.02. Nabas et al. [44], also reported pH 3.42±0.02 of royal jelly. Tiwari [45], found the pH of different royal jelly samples, ranging between 3.43 to 3.89 to 3.91 in March, January, April, respectively implying that the sample collected in January was more acidic than those collected in the rest of the months. Isidrov et al. [42], reported that pure royal jelly has a mean pH value of 3.95. The present result lies within the ranges given by FSSAI [2].

Moisture Content

The statistical analysis of moisture content among the seasons indicated no significant difference (p>0.05) and revealed consistency of royal jelly at 64.00 per cent, 64.33 per cent 66.67 per cent in spring, summer and autumn, respectively. The results on Total Soluble Solids (TSS) present in royal jelly showed no significant variation as supported by a p-value of 0.739 (p>0.05) and it varied from 36.00 per cent, 35.67 per cent and 33.33 per cent in spring, summer and autumn, respectively. The high moisture content in autumn compared to spring and summer can be attributed wetter conditions, high temperature and high humidity (spring, autumn) that contribute to higher moisture retention, while drier conditions and low temperatures (summer) help retain higher moisture levels. Different flowering plants in each season produce nectar with varying water content, influencing the composition of royal jelly. Spring and autumn florals often have more moisture-rich nectar than summer florals. The present study is in line with studies by Garcia-Amoedo and Almeida-Muradian [46], conducted physicochemical analysis of fresh RJ were 67.58 per cent. Sereia et al. [43], reported an average range of moisture at 66.23- 67.81 per cent from royal jelly in A. mellifera. Nabas et al. [44], also reported moisture content to be 61.5±0.25 per cent. Kausar et al. [47], also reported that the total moisture content in fresh royal jelly at 60 per cent. In present studies, the results showed no significant variation in Total Soluble Solids (TSS) present in royal jelly across the seasons, as supported by a p-value of 0.739 (p>0.05). The TSS was relatively consistent with mean 35 per cent, recorded at 36.00 per cent, 35.67 per cent and 33.33 per cent in spring, summer and autumn, respectively. Tiwari [45], found the moisture content and solids content royal jelly at 64.35-68.57 per cent and 31.43-35.65 per cent. The mean moisture content obtained in royal jelly samples was 65.33 per cent, which is significantly higher than the average moisture content reported by Zhang et al. [30], for fresh RJ samples, which was 53.3 per cent. Sabatini et al. [9], reported that the moisture content in royal jelly typically ranges between 60 per cent and 70 per cent. The analysis showed significant variations in ash content across the seasons (p<0.05). The mean ash content in royal jelly samples were 2.00±0.00 in spring, 2.12±0.00 in summer and 2.01±0.00 in autumn, with an overall mean of 2.04. These results suggest that seasonal variations had a statistically significant impact on ash content, with the highest ash content recorded during the summer season. Nabas et al. [44], reported 1.10±0.05 per cent ash content in royal jelly. Kausar and More [47], also reported 1.22 per cent ash content in fresh royal jelly.

Lipid and Protein Content

The statistical analysis revealed no significant difference in lipid content (p>0.05) and the content varied as 7.50 per cent in spring and summer to 6.87 per cent in Autumn. Protein content demonstrated a significant difference across the seasons (p < 0.05). The significantly highest protein content was recorded in summer (17.49%), followed by spring (17.12%) and autumn (16.00%) with mean 16.87 per cent. This study indicated that seasonal factors significantly influenced protein levels with summer conditions potentially favoring higher protein levels accumulation in royal jelly samples. The mean value obtained was 16.87 per cent, which is consistent with the findings of Lercker et al. [48], who reported an average crude protein content of 17 per cent in fresh royal jelly samples. Shahidi & Zhong [49], highlighted that variations in protein content among different royal jelly samples may be linked to its antioxidant activity. Determining changes in protein content is an effective way to assess the quality of royal jelly.

Protein content (%) showed a significant seasonal variation (p=0.036), with higher protein content in Summer. No significant differences were found for ash content, carbohydrates, DPPH, flavonoids, lipids, moisture content, phenol, TSS and pH across the seasons. It may be concluded that the only parameter showing a significant seasonal difference is protein where summer has higher values compared to spring and autumn.

Carbohydrate Content

Carbohydrate levels remained relatively consistent across the three seasons, as evidenced by the lack of statistical significance (p>0.05). While there was a slight decrease in carbohydrate content from spring (9.14%) to summer (8.77%) and autumn with mean of 8.96 per cent these differences were not statistically meaningful. The stability in carbohydrate levels suggests that seasonal variations had a negligible effect on carbohydrate content in the samples. Overall, the findings highlight a significant seasonal influence on protein content, while lipid and carbohydrate levels remained largely unaffected by seasonal changes.

DPPH, Phenol and Flavonoids Content

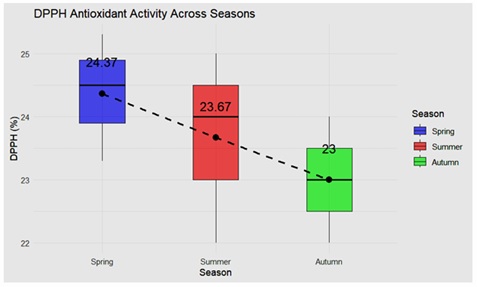

The result (p>0.05) indicated no significant difference in DPPH antioxidant activity across spring, summer and autumn with mean DPPH content of 23.68% (Figures 1 & 2). The recorded values showed a slight decrease, from 24.37 per cent in spring to 23.67 per cent in summer and 23.00 per cent in autumn. Despite this minor variation, the changes were not statistically significant, suggesting that seasonal factors had a negligible impact on antioxidant activity as measured by DPPH (Table 2). Phenolic content also showed no significant variation across the seasons, with a p-value of 0.978 (p>0.05). The phenolic content values remained fairly stable with mean 20.69μg/mg, recorded at 20.40μg/mg in spring, 20.67μg/mg in summer, and 21.00μg/mg in autumn. These results indicate that the phenolic content of the samples was consistent across seasonal changes. The analysis revealed no significant difference in flavonoid content across the seasons, as evidenced by a p-value of 0.983 (p>0.05) with a mean value of 1.38μg/mg. Flavonoid content values were consistent, recorded at 1.37μg/mg in spring, 1.40μg/mg in summer, and 1.36μg/mg in autumn. This suggests that flavonoid levels were unaffected by seasonal variation. In summary, the findings demonstrate that DPPH antioxidant activity, phenolic content, and flavonoid content remained relatively stable across the three seasons, with no statistically significant differences observed. This indicates a high degree of consistency in these biochemical parameters irrespective of seasonal changes. Nabas et al. [44], reported similar content of total phenolics 23.3±0.92μg/mg RJ, total flavonoids 1.28±0.09μg/mg RJ. Kazemi et al. [34], also found the similar amounts of phenols (22.98±0.34µg/mg for commercial and 21.99±0.41µg/mg for raw).

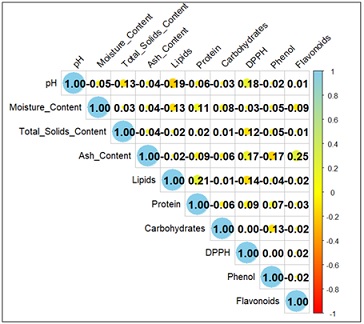

Figure 1: Correlation analysis of physicochemical and bioactive properties of royal jelly from A. mellifera.

Figure 1: Correlation analysis of physicochemical and bioactive properties of royal jelly from A. mellifera.

Note: In the correlation heatmap, the color gradient, Blue: Represents strong positive correlations (closer to +1). A value near +1 means that as one parameter increases, the other also increases proportionally. White: Represents no correlation (value around 0). This indicates no linear relationship between the parameters. Red: Represents strong negative correlations (closer to -1). A value near -1 means that as one parameter increases, the other decreases proportionally.

Figure 2: DPPH full form content in royal jelly.

|

S. No. |

Micronutrient |

Concentration (ppm/g) |

|

1 |

Iron (Fe) |

0.786 ppm |

|

2 |

Magnesium (Mg) |

645.800 ppm |

|

3 |

Zinc (Zn) |

0.351 ppm |

Table 2: Micronutrient concentration in royal jelly from A. mellifera.

Micronutrients

In present studies, the mean micronutrients concentration in royal jelly recorded in iron (Fe) was 0.786ppm/gm, 645.800ppm/gm in magnesium (Mg) and for zinc (Zn) it was 0.351ppm/gm (Table 3). However, other micronutrients (Cr, Cu, Ni and Mn) were also estimated but no record was found. Stocker et al. [50], and Balkansan et al. [51], reported much lower Ca, Mg, Fe and Zn levels in royal jelly. Tiwari [45], reported 58.85mg/100g (Ca), 57.24mg/100g (Mg), 0.28mg/100g (Fe), and 6.26mg/100g (Zn) that aligned with the findings of Bogdanov et al. [16]. The present study reported that micronutrient variations are likely influenced by seasonal changes and botanical sources. These differences highlight the essential role of micronutrients in biomedical functions making mineral analysis crucial for assessing royal jelly quality.

|

Parameter (% by mass) |

ISO Permissible Limit |

|

Moisture |

62-68.5 |

|

10-hydroxy-2-decenoic acid |

1.4 |

|

Protein |

11-18 |

|

Total sugar |

7-18 |

|

Glucose |

2-9 |

|

Total lipid |

2-8 |

Table 3: Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) imposed International Organization for Standardization (ISO) standard for royal jelly in India (2019).

Correlation Analysis of Physicochemical and Bioactive Properties in Royal Jelly

The correlation heatmap (Figure 1) visualizes the relationships between various physicochemical and bioactive parameters of royal jelly. Parameters like pH, moisture content, total solids content and others showed strong positive correlations within their groups (diagonal micronutrients with values of 1, as expected). Ash content represented a moderate positive correlation with phenol (0.25) suggesting a potential link between mineral content and phenolic compounds. Weak correlations (close to 0) were also observed between lipids and DPPH (-0.04) or phenol and flavonoids (-0.02). These indicated minimal relationships or independence between the respective parameters. Similarly, carbohydrates exhibit negative correlations with some bioactive properties like DPPH (-0.17) and phenol (-0.09), indicating a potential inverse relationship. Hence it is interpreted that the correlations between physicochemical properties and bioactive properties may not directly influence each other significantly. Whereas, the moderate positive correlations between ash content and phenol may imply that certain micronutrient components contribute to antioxidant or bioactive properties as well.

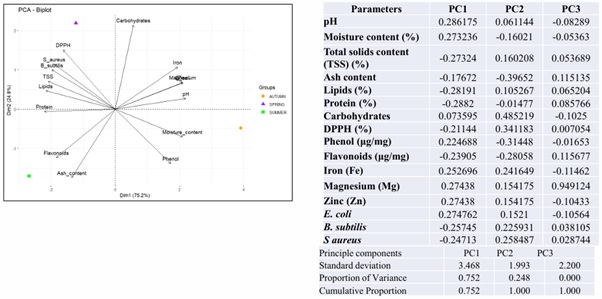

Principle Component Analysis (PCA)

PCA is a key chemometric tool in food science research [52], that reduces data dimensionality by transforming correlated variables into uncorrelated principal components. It enables visual differentiation and grouping of samples. In this study, multivariate PCA was applied to analyse the physicochemical properties of royal jelly from A. mellifera in Himachal Pradesh. PC1 has the highest standard deviation (3.468) followed by PC3 (2.20) and PC2 (1.993) that suggests that PC1 has the most variation in the data. The cumulative proportion for PC1 is 0.752, which means it accounts for 75.2% of the total variance, it is 1.000 for PC2 and PC3 meaning PC1 and PC2 together explain 100% of the variance (Figure 3).

Figure 3: The principal component analysis (PCA) biplot visualizes the contribution and relationship of different variables in two principal components: Dimension 1 (PC1) explains 75.2% of the total variance, indicating it captures most of the variability in the dataset. Dimension 2 (PC2) explains 24.8% of the total variance contributing additional but lesser variation. Together, these two dimensions account for 100% of the variability, making this a strong summarization of the dataset. Variables pointing in the same direction are positively correlated (pH and moisture, phenol, Mg, Zn, Fe), at opposite directions are negatively correlated and at right angles are independent.

Figure 3: The principal component analysis (PCA) biplot visualizes the contribution and relationship of different variables in two principal components: Dimension 1 (PC1) explains 75.2% of the total variance, indicating it captures most of the variability in the dataset. Dimension 2 (PC2) explains 24.8% of the total variance contributing additional but lesser variation. Together, these two dimensions account for 100% of the variability, making this a strong summarization of the dataset. Variables pointing in the same direction are positively correlated (pH and moisture, phenol, Mg, Zn, Fe), at opposite directions are negatively correlated and at right angles are independent.

Note:

- Autumn (in orange circle) that is located towards the right, indicating its link with high moisture content, phenol, iron, magnesium, and pH.

- Spring (purple triangle) is located at the top, suggesting a strong correlation with DPPH (antioxidant activity).

- Summer (green square) is on the left side and aligns with high flavonoid and ash content.

The principal component analysis (PCA) biplot (Figure 3) visualizes the contribution and relationship of different variables in two principal components. It revealed that strongly contributing variables like moisture, phenol, and pH have high positive loadings on PC1, indicating they are highly correlated with this dimension. Flavonoids have a strong negative contribution, meaning they are negatively associated with PC1. The carbohydrates and DPPH contribute significantly to PC2, suggesting that they explain variations distinct from PC1. TSS, lipids and protein are clustered near the origin, suggesting lower contributions to both components. It is found that moisture, phenol, and pH are the most dominant factors influencing the first principal component. Carbohydrates and DPPH uniquely contribute to the second principal component. Flavonoids are inversely related to the main contributors of PC1.

Seasonal differences in the biochemical makeup of samples are successfully distinguished using PCA. Higher levels of moisture, minerals, and phenol content are characteristics of autumn. Antioxidants are abundant in the spring (DPPH).

Higher levels of ash and flavonoids are associated with summer. Strong clustering in the sample suggests that biochemical characteristics vary with the season.

UHPLC-Based Profiling and Elemental Analysis of Royal Jelly

The protein content of the royal jelly sample was 24.91g/100g (as measured by the SLS/CH/STP-16 method), indicating a substantial nutritional value. The sample analysis by UHPLC revealed that among various phenolic compounds and flavonoids, caffeic acid, ferulic acid and gallic acid were quantified at 0.92mg/L, 1.60mg/L and 1.10mg/L, respectively. However, no detection of Apigenin and riboflavin (vitamin B2) was found in the sample (Table 4).

|

S. No |

Test Parameters |

Unit |

Test Method |

Result |

|

1 |

Caffeic |

mg/L |

By UHPLC |

0.92 |

|

2 |

Protein |

g/100g |

SLS/CH/STP - 16 |

24.91 |

|

3 |

Ferulic |

mg/L |

By UHPLC |

1.60 |

|

4 |

Gallic |

mg/L |

By UHPLC |

1.10 |

|

5 |

Apigenin |

mg/L |

By UHPLC |

ND |

|

6 |

Quercetin |

mg/L |

By UHPLC |

0.33 |

|

7 |

Chrysin |

mg/L |

By UHPLC |

1.39 |

|

8 |

Hesperetin |

mg/L |

By UHPLC |

1.96 |

|

9 |

Vitamin B2 |

mg/L |

By UHPLC |

ND |

|

10 |

Vitamin C |

mg/L |

By UHPLC |

1.27 |

|

Mineral Count |

||||

|

11 |

Iron |

mg/kg |

SLS/CH/STP - 02 |

19.68 |

|

12 |

Copper |

mg/kg |

SLS/CH/STP - 02 |

5.37 |

|

13 |

Sodium |

mg/kg |

SLS/CH/STP - 02 |

98.88 |

|

14 |

Calcium |

mg/kg |

SLS/CH/STP - 02 |

630.04 |

|

15 |

Magnesium |

mg/kg |

SLS/CH/STP - 02 |

235.93 |

|

16 |

Potassium |

mg/kg |

SLS/CH/STP - 02 |

2938.92 |

Table 4: UHPLC-based profiling and elemental analysis of royal jelly.

Among flavonoid compounds, quercetin, chrysin and hesperidin were detected at concentrations of 0.33mg/L, 1.39mg/L and 1.96mg/L, respectively. The ascorbic acid (Vitamin C) was present at a concentration of 1.27mg/L (Table 4).

Royal jelly consists of flavanones (hesperidin), flavones (chrysin) and flavonols (quercetin), polyphenols including caffeic acid and ferulic acid are well-known antimicrobial agents that compromise bacterial cell walls and alter membrane permeability. Their ability to destabilize membranes has been demonstrated across both E. coli and S. aureus. Phenolic acids, including caffeic acid play a crucial role in antimicrobial activity and antioxidant capacity [53]. Gallic acid (1.10mg/L) exerts antimicrobial activity via oxidative stress induction; efficacy has been validated especially against Gram-positive bacteria, including S. aureus and B. subtilis [54]. These of chemical components found in royal jelly exhibit several pharmacological properties, including antibacterial, antiaging, antiallergic, anticancer, antidiabetic, anti inflammatory, immunomodulatory and neuroprotective effects. Chrysin, in particular, has been shown to impede S. aureus and E. coli growth by attenuating quorum sensing. Vitamin C (1.27mg/L) may enhance bacterial membrane damage and promote ROS-mediated cellular damage, augmenting the ground-level phenolic activity [55].

The analysis of mineral content indicated that potassium was the predominant mineral, with a concentration of 2938.92mg/kg, followed by calcium (630.04mg/kg), magnesium (235.93mg/kg) and sodium (98.88mg/kg) (Table 4). Among the trace elements, iron and copper were detected at 19.68mg/kg and 5.37mg/kg, respectively.

Copper plays a crucial role in catalyzing ROS generation, damaging bacterial proteins, membranes, and DNA. Its broad-spectrum bactericidal capacity against E. coli and S. aureus is well documented. Elevated levels of potassium, calcium, and magnesium may facilitate structural stability and proper function of antimicrobial peptides (e.g., royalisin, MRJPs) intrinsic to royal jelly [55].

Antibacterial Assay

The inhibitory effect of royal jelly concentrations (Table 5, Figures 4 & 5) against E. coli (NCTC 10418) in spring 2024 revealed no significant variations in zone of inhibition. The 50 per cent concentration showed a minimum 10.33±0.33mm zone of inhibition, whereas 100 per cent concentration showed 11.33±0.33mm zone of inhibition compared to positive control i.e. 12.17mm. Similarly, in summer season, significant variations were recorded for the zone of inhibition in royal jelly concentrations. It was maximum for positive control (12.17mm), which was statistically at par with 100 per cent concentration of royal jelly (10.67±0.67mm), which was further at par with zone of inhibition for 50 per cent royal jelly concentration (9.67±0.33mm). During autumn season, the zone of inhibition was significantly maximum in the positive control (12.17mm) with statistically similar zone of inhibition in 100 per cent (12.00±0.58mm) royal jelly concentration, whereas a significantly minimum zone of inhibition was recorded in 50 per cent concentration of royal jelly (8.33±0.33mm).

|

Pathogen |

Escherichia coli (NCTC 10418) |

Bacillus subtilis (ATCC 6633) |

Staphylococcus aureus (NCTC 3750) |

||||||

|

Seasons Concentration (%) |

Spring |

Summer |

Autumn |

Spring |

Summer |

Autumn |

Spring |

Summer |

Autumn |

|

50 |

10.33±0.33 mm |

9.67±0.33 mm |

8.33±0.33 mm |

23.00±1.53 mm |

18.33±1.67 mm |

15.00±0.00 mm |

13.00±0.00 mm |

12.67±0.33 mm |

12.33±0.33 mm |

|

100 |

11.33±0.33 mm |

10.67±0.67 mm |

12.00±0.58 mm |

26.33±0.88 mm |

24.67±0.33 mm |

20.00±0.00 mm |

20.33±0.33 mm |

20.00±0.00 mm |

19.33±0.33 mm |

|

Positive control (Tetracycline) |

12.17mm |

25.00mm |

23.50mm |

||||||

|

CD(0.05) |

NS |

1.66 |

1.52 |

NS |

3.46 |

0.68 |

0.69 |

1.36 |

0.96 |

|

Negative control (sterile water) |

No zone of inhibition |

||||||||

Table 5: Inhibitory effect of royal jelly against selected pathogens across spring, summer and autumn season.

Note: ± denotes standard error

Figure 4: Steps in antibacterial activity assessment. a: Pure bacterial culture; b,c: Swabbing of bacterial culture evenly onto the agar plate; d: Making of wells (5mm) using sterile tip in the agar; e: Royal jelly sample (100% and 50% diluted); f: Pipetting of royal jelly samples, Positive control (Tetracycline) and negative control (sterile water) into the wells; g: Measurement of zone of inhibition (in mm) after 48 hours of incubation at 37°C.

Figure 4: Steps in antibacterial activity assessment. a: Pure bacterial culture; b,c: Swabbing of bacterial culture evenly onto the agar plate; d: Making of wells (5mm) using sterile tip in the agar; e: Royal jelly sample (100% and 50% diluted); f: Pipetting of royal jelly samples, Positive control (Tetracycline) and negative control (sterile water) into the wells; g: Measurement of zone of inhibition (in mm) after 48 hours of incubation at 37°C.

Figure 5: Inhibitory effect of 50% and 100% Royal Jelly (RJ) concentrations against Escherichia coli (NCTC 10418) (A,B,C), Staphylococcus aureus (NCTC 3750) (D,E,F) and Bacillus subtilis (ATCC 6633) ((G,H,I) in spring (A,B,C) summer (D,E,F) and autumn (G,H,I) TE: Tetracycline (Positive control) ; NC: Negative control (sterile water).

Figure 5: Inhibitory effect of 50% and 100% Royal Jelly (RJ) concentrations against Escherichia coli (NCTC 10418) (A,B,C), Staphylococcus aureus (NCTC 3750) (D,E,F) and Bacillus subtilis (ATCC 6633) ((G,H,I) in spring (A,B,C) summer (D,E,F) and autumn (G,H,I) TE: Tetracycline (Positive control) ; NC: Negative control (sterile water).

The results of inhibitory effect of royal jelly concentrations against B. subtilis (ATCC 6633) in spring season of 2024 revealed no significant variations in zone of inhibition, but detected that zone of inhibition was maximum for 100 per cent (26.33±0.88mm) concentrations of royal jelly as compared to 50 per cent concentration (23.00±1.53mm) and positive control (25.00mm). However, during summer season significant variations have been recorded for inhibitory effect for royal jelly with maximum zone of inhibition for positive control (25.00mm) which was statistically similar to 100 per cent royal jelly concentration (24.67±0.33mm) while significantly minimum for 50 per cent concentration (18.33±1.67mm). During autumn season the significant variations recorded were varied as positive control (25.00mm) followed by 100 per cent (20.00±0.00mm) concentration and significantly minimum for 50 per cent concentration (15.00±0.00mm).

The data analysis on inhibitory effect of royal jelly concentrations against S. aureus (NCTC 3750) in spring season of 2024 revealed significant variations from maximum zone of inhibition in positive control (23.50mm) followed by 20.33±0.33mm in 100 per cent and 13.00±0.00mm in 50 per cent royal jelly concentration. During summer and autumn seasons, the zone of inhibition varied from 23.50mm in positive control, 20.00±0.00mm and 19.33±0.33, 12.67±0.33 and 12.33±0.33 in 100 per cent and 50 per cent concentrations of royal jelly, respectively.

The present study is in correspondence with the fact that has been reported that royal jelly has a powerful antibiotic effect against E. coli, Salmonella, Proteus, B. subtilis and S. aureus bacteria. The present study reported 11.33±0.33mm, (26.33±0.88mm) and 20.33±0.33mm in 100 per cent zone of inhibition in E. coli, Bacillus subtilis and S. aureus, respectively. Similar results have been reported in a study by Oncul et al. [56], on antimicrobial effects of royal jelly sample (100%) on S. aureus, with an inhibition zone of 21.00±1.10mm marking the strongest effect observed against this bacterium and S. aureus is known for its rapid resistance to antibiotics, which complicates the treatment of hospital and community-acquired infections. The undiluted royal jelly sample created an inhibition zone of 14.7±0.6mm on S. aureus, 5.7±0.6mm on P. aeruginosa, 9.7±0.6mm on E. coli [57,58], at a concentration of 15mg/ml, RJ caused the largest inhibition zones: 25mm against B. subtilis and 22mm against S. aureus. According to Nath et al. [59], the antibacterial properties of Royal Jelly (RJ) from A. cerana exhibited the highest activity against B. subtilis (25mm inhibition zone at 100μg/ml), followed by E. coli (22mm) while S. aureus showed no response at any concentration. Ogur and Daya [60], also reported that 100 per cent concentration (undiluted royal jelly) exhibited the highest antimicrobial activity. Royal Jelly (RJ) has demonstrated significant antibacterial properties against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Studies have shown RJ's effectiveness against a range of bacterial pathogens, such as S. aureus, E. coli, B. cereus, P. aeruginosa and L. monocytogenes [58,61]. Notably, RJ exhibits stronger activity against Gram-positive bacteria, as demonstrated in various studies where inhibition zones were larger for organisms like B. subtilis and S. aureus [59,62]. Geographic origin, concentration and the type of RJ also play critical roles in its antimicrobial efficacy. For example, RJ from mountain regions demonstrated superior antibacterial activity against E. coli and P. aeruginosa [58,62]. Several studies have explored the potential of RJ as an alternative or complementary antimicrobial agent. For instance, Oncul et al. [56], reported potent activity of RJ against S. aureus (inhibition zone of 21.00±1.10mm) at 100 per cent and 50 per cent concentrations. Similarly, Garcia et al. [57], highlighted the variation in RJ activity against multiple bacterial strains, with inhibition zones ranging from 5.7mm to 20.7mm depending on the bacterial species and RJ concentration. Other research corroborated these findings, emphasizing the variability in antimicrobial activity due to genetic and environmental factors influencing RJ composition [63,64].

Conclusion

Moderate positive correlations between specific parameters like ash content and phenol suggest a possible link between nutrient content and antioxidant activity. Comparative studies also revealed that RJ's antibacterial potential rivals or complements standard antibiotics, making it a promising candidate for treating infections caused by antibiotic-resistant bacteria, particularly S. aureus and B. subtilis. The study highlights the therapeutic potential of RJ as a natural antimicrobial agent, particularly for managing Gram-positive bacterial infections with further research needed to explore its mechanisms of action and optimize its use in clinical settings. These findings emphasize the potential of royal jelly and probiotics as a functional food with antioxidant benefits. Thus, this study recommends that royal jelly from A. mellifera in Himachal Pradesh is well within the limit of FSSAI.

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful to the Indian Council of Agriculture Research, New Delhi, through the project coordinator, All India Coordinated Research Project on Honey bees and Pollinators (AICRP) & ICSSR for providing financial assistance.

References

- Pasupuleti VR, Sammugam L, Ramesh N, Gan SH (2017) Honey, propolis, and royal jelly: A comprehensive review of their biological actions and health benefits. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 1: 1259510.

- FSSAI (2019) Food Safety and Standard Authority of India.

- Chand B, Kumari I, Kumar R (2021) Evolution of apiculture, history and present scenario in honey. CRC Press, USA.

- Vazhacharickal PJ (2021) A review on health benefits and biological action of honey, propolis and royal jelly. Journal of Medicinal Plants Studies 9: 1-13.

- Molan PC (1999) Why honey is effective as a medicine. 1. Its use in modern medicine. Bee World 80: 80-92.

- Cherbuliez T (2013) Apitherapy-The use of honeybee products. In: Biotherapy-History, Principles and Practice. Springer, Netherlands.

- Kayshar MS, Jubayer MF, Mazumder MAR, Rahman A, Peter D, et al. (2024) Royal Jelly. In: Honey Bees, Beekeeping and Bee Products. CRC Press, USA.

- Hassanyar AK, Huang J, Nie H, Li Z, Hussain M, et al. (2023) The association between the hypopharyngeal glands and the molecular mechanism which honey bees secrete royal jelly. Journal of Apicultural Research 64: 281-296.

- Sabatini AG, Marcazzan GL, Caboni MF, Bogdanov S, Almeida-Muradian LBD (2009) Quality and standardisation of royal jelly. Journal of ApiProduct and ApiMedical Science 1: 1-6.

- Fujita T, Kozuka-Hata H, Ao-Kondo H, Kunieda T, Oyama M, et al. (2013) Proteomic analysis of the royal jelly and characterization of the functions of its derivation glands in the honeybee. Journal of Proteome Research 12: 404-411.

- Fratini F, Cilia G, Mancini S, Felicioli A (2016) Royal Jelly: An ancient remedy with remarkable antibacterial properties. Microbiological Research 192: 130-141.

- Eteraf-Oskouei T, Najafi M (2013) Traditional and modern uses of natural honey in human diseases: A review. Iranian Journal of Basic Medical Sciences 16: 731-742.

- Kataki MS, Rajkumari A, Kakoti BB (2019) Functional foods and nutraceuticals: An overview of the clinical outcomes and evidence-based archive. Nanotechnology, CRC Press, USA.

- Ramadan MF, Al-Ghamdi A (2012) Bioactive compounds and health-promoting properties of royal jelly: A review. Journal of Functional Foods 4: 39-52.

- Buttstedt A, Muresan CI, Lilie H, Hause G, Ihling CH, et al. (2018) How honeybees defy gravity with royal jelly to raise queens. Current Biology 28: 1095-1100.

- Bogdanov S (2011) Royal jelly, bee brood: Composition, health, medicine: A review. Lipids 3: 8-19.

- Ramanathan ANKG, Nair AJ, Sugunan VS (2018) A review on Royal Jelly proteins and peptides. Journal of Functional Foods 44: 255-264.

- Miyata Y, Sakai H (2018) Anti-cancer and protective effects of royal jelly for therapy-induced toxicities in malignancies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 19: 3270.

- Kunugi H, Ali AM (2019) Royal jelly and its components promote healthy aging and longevity: from animal models to humans. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 20: 4662.

- Fontana R, Mendes MA, Souza BM, Konno K, César LMM, et al. (2004) Jelleines: A family of antimicrobial peptides from the royal jelly of honeybees (Apis mellifera). Peptides 25: 919-928.

- Bincoletto C, Eberlin S, Figueiredo CA, Luengo MB, Queiroz ML (2005) Effects produced by Royal Jelly on haematopoiesis: Relation with host resistance against Ehrlich ascites tumour challenge. International Immunopharmacology 5: 679-688.

- Kamakura M, Mitani N, Fukuda T, Fukushima M (2001) Antifatigue effect of fresh royal jelly in mice. Journal of Nutritional Science and Vitaminology 47: 394-401.

- Ahmad S, Campos MG, Fratini F, Altaye SZ, Li J (2020) New insights into the biological and pharmaceutical properties of royal jelly. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 21: 382.

- Detienne G, De Haes W, Ernst UR, Schoofs L, Temmerman L (2014) Royalactin extends lifespan of Caenorhabditis elegans through epidermal growth factor signalling. Experimental Gerontology 60: 129-135.

- Khazaei M, Ansarian A, Ghanbari E (2018) New findings on biological actions and clinical applications of royal jelly: A review. Journal of Dietary Supplements 15: 757-775.

- El-Guendouz S, Machado AM, Aazza S, Lyoussi B, Miguel MG, et al. (2020) Chemical characterization and biological properties of royal jelly samples from the Mediterranean area. Natural Product Communications 15: 1-13.

- Bilikova K, Krakova TK, Yamaguchi K, Yamaguchi Y (2015) Major royal jelly proteins as markers of authenticity and quality of honey. Archives of Industrial Hygiene and Toxicology 66: 259-267.

- Doolittle GM (1888) Scientific Queen Rearing as Practically Applied. Thomas G. Newman & Son, Chicago, USA.

- Kheyri H, Cribb BW, Reinhard J, Claudianos C, Merritt DJ (2012) Novel actin rings within the secretory cells of honeybee royal jelly glands. Cytoskeleton 69: 1032-1039.

- Zhang L, Fang Y, Li R, Feng M, Han B, et al. (2012) Towards posttranslational modification proteome of royal jelly. Journal of Proteomics 75: 5327-5341.

- Buttstedt A, Moritz RF, Erler S (2013) More than royal food-Major royal jelly protein genes in sexuals and workers of the honeybee Apis mellifera. Frontiers in Zoology 10: 72.

- Hu FL, Bíliková K, Casabianca H, Daniele G, Espindola FS, et al. (2019) Standard methods for Apis mellifera royal jelly research. Journal of Apicultural Research 58: 1-68.

- Horwitz W, Latimer G (2000) Association of Analytical Chemists (AOAC).

- Kazemi V, Eskafi M, Saeedi M, Manayi A, Hadjiakhoondi A (2019) Physicochemical properties of royal jelly and comparison of commercial with raw specimens. Jundishapur Journal of Natural Pharmaceutical Products 14: 64920.

- Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randakk RJ (1951) Protein measurement with Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem 193: 265-275.

- AOAC (1980) Official Methods of Analysis of the Analytical Chemists. Association of Official Analytical Chemists, USA.

- Biesaga M, Pyrzynska K (2013) Stability of bioactive polyphenols from honey during different extraction methods. Food Chemistry 136: 46-54.

- Pauliuc D, Dranca F, Oroian M (2020) Antioxidant activity, total phenolic content, individual phenolics and physicochemical parameters suitability for Romanian honey authentication. Foods 9: 306.

- Muresan CI, Mãrghitas LA, Dezmirean DS, Bobis O, Bonta V, et al. (2016) Quality Parameters for commercialized Royal Jelly. Bulletin of the University of Agricultural Sciences & Veterinary Medicine Cluj-Napoca. Animal Science & Biotechnologies

- Eshraghi S, Seifollahi F (2003) Antibacterial effects of royal jelly on different strains of bacteria. Iranian Journal of Public Health 32: 25-30.

- Lercker G (2003) Royal jelly: Composition, authenticity and adulteration. In: Proceedings of the Conference Strategies for the valorization of hive products. University of Molise, Campobasso.

- Isidrov VA, Czyzewska V, Jankowsk M, Bakier S (2011) Determination of royal jelly acid in honey. Journal of Food Chemistry 124: 387- 391.

- Sereia MJ, Toledo VDAAD, Furlan AC, Faquinello P, Maia FMC, abd Wielewski, P (2013) Alternative sources of supplements for Africanized honeybees submitted to royal jelly production. Acta Scientiarum Animal Sciences 35: 165-171.

- Nabas ZM, Haddadin MS, Nazer IK (2014) The influence of royal jelly addition on the growth and production of short chain fatty acids of two different bacterial species isolated from infants in Jordan. Pakistan Journal of Nutrition 13: 43.

- Tiwari S (2018) Physico-chemical, biochemical and structural characterization of royal jelly and bee pollen of different floral origins.

- Garcia-Amoedo LH, Almeida-Muradian LBD (2007) Physicochemical composition of pure and adulterated royal jelly. Química Nova30: 257-259.

- Kausar SH, More VR (2019) Royal Jelly. Organoleptic characteristics and physicochemical properties. Lipids6: 20-24.

- Lercker G, Caboni MF, Vecchi MA, Sabatini AG, Nanetti A (1993) Characterization of the main constituents of royal jelly. Apicoltura 8: 27-37.

- Shahidi F, Zhong Y (2011) Revisiting the polar paradox theory: A critical overview. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 59: 3499-3504.

- Stocker A, Schramel P, Kettrup A, Bengsch E (2005) Trace and mineral elements in royal jelly and homeostatic effects. Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology 19: 183-189.

- Balkanska R, Mladenova E, Karadjova I (2017) Quantification of selected trace and mineral elements in royal jelly from Bulgaria by ICP-OES and etaas. Journal of Apicultural Science61: 223-232.

- Yu PQ (2005) Applications of hierarchical Cluster Analysis (CLA) and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) in feed structure and feed molecular chemistry research, using synchrotron-based Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) micro spectroscopy. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 53: 7115-7127.

- Niu Y, Wang K, Zheng S, Wang Y, Ren Q, et al. (2020) Antibacterial Effect of Caffeic Acid Phenethyl Ester on Cariogenic Bacteria and Streptococcus mutans Biofilms. Agents Chemother 64: 251.

- Nainu F, Masyita A, Bahar MA, Raihan M, Prova SR, et al. (2021) Pharmaceutical prospects of bee products: Special focus on anticancer, antibacterial, antiviral, and antiparasitic properties. Antibiotics10: 822.

- Bava R, Puteo C, Lombardi R, Garcea G, Lupia C, et al. (2025) Antimicrobial Properties of Hive Products and Their Potential Applications in Human and Veterinary Medicine. Antibiotics 14: 172.

- Oncul O, Erdemoglu A, Ozsoy MF, Altunay H, Ertem Z, et al. (2002) Nasal Staphylococcus aureus carriage in healthcare staff. Klimik Journal 15: 74-77.

- García MC, Finola MS, Marioli JM (2010) Antibacterial activity of Royal Jelly against bacteria capable of infecting cutaneous wounds. Journal of ApiProduct and ApiMedical Science 2: 93-99.

- Moselhy WA, Fawzy AM, Kamel AA (2013) An evaluation of the potent antimicrobial effects and unsaponifiable matter analysis of the royal jelly. Life Science Journal 10: 290-296.

- Nath, KGRA, Krishna SBA, Smrithi S, Nair, AJ, Sugunan VS (2019) Biochemical characterization and biological evaluation of royal jelly from Apis cerana. Journal of Food Technology and Food Chemistry 2: 101.

- Ogur S, Dayan Y (2022) Antimicrobial activities of natural honeys and royal jellys on some pathogenic bacteria. Balikesir Üniversitesi Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü Dergisi 24: 672-689.

- Boukraa L (2008) Additive activity of royal jelly and honey against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Alternative Medicine Review 13: 330-333.

- Mohammad F, Koohsari H, Ghaboos SH (2022) Antibacterial and antioxidant activity of royal jelly collected from geographical regions with different climates in the north of Iran. Bulgarian Journal of Veterinary Medicine 25: 397-410.

- Mierzejewski M (2014) The antimicrobial effects of royal jelly, propolis and honey against bacteria of clinical significance in comparison to three antibiotics. Coll Arts Sci Biol.

- Isla MI, Craig A, Ordoñez R, Zampini C, Sayago J, et al. (2011) Physico chemical and bioactive properties of honeys from Northwestern Argentina. LWT-Food Science and Technology 44: 1922-1930.

Citation: Bhatia S, Rana K, Devi S, Singh SJ (2025) Profiling and Bioactivity of Apis Mellifera Royal Jelly in Himachal Pradesh. HSOA J Food Sci Nutr 11: 228.

Copyright: © 2025 Simran Bhatia, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.