Quality of Life of Patients with Extra-Ocular Retinoblastoma in Abidjan

*Corresponding Author(s):

Diomandé GFDepartment Of Ophthalmology, Center Hospital University Of Bouaké, Cote D'Ivoire

Tel:+225 46804233/03123230,

Email:diomandgosse@ymail.com

Abstract

Introduction: The objective of this study is to contribute to the assessment of the quality of children’s life with extra-ocular retinoblastoma in the ophthalmology and pediatric departments at the University Hospital Center of Treichville.

Materials and methods: This was a retrospective and cross-sectional descriptive study of 45 patients aged 0 to 15 years with extra-ocular retinoblastoma with histopathological and/or CT scan diagnosis. It took place jointly in the onco-ophthalmology, onco-pediatric and histopathology departments at the University Hospital Center of Treichville for a period of 4 years. Data have been collected from consultation registers and patient follow-up records. Some patients were seen again for further examination. The socio-demographic and clinical characteristics before the consultation have been studied. The quality of life has been assessed thanks to QUALIN questionnaire for children from 0 to 3 years old and AUQUEI questionnaire for children from 4 to 12 years old. The analysis is based on the clinical and socio-characteristics, the para-clinical examinations and the treatments carried out in the admission services.

Results: The mean age was 35.5 months. On admission, 43 eyes (96%) were at stage E and 2 eyes (4%) at stage D. Exophthalmos was the main motive for consultation (95.6%). Metastases were present mainly to the optic nerve in 37 patients (90.2%). Enucleation was performed in 42.2% of cases, chemotherapy in 75.6% of cases against only 4.4% for radiotherapy.

Discussion: In our study, poor quality of life was found in 80% of cases. The child’s well being is influenced by the inaccessibility to adequate care, the low socio-economic level, the lack of awareness of the population at the origin of the ignorance of retinoblastoma’s signs at the beginning stage.

Conclusion: Extra-ocular retinoblastoma has a significant impact on children’ well being and their families. This condition poses a real public health problem like most neoplastic conditions, hence the importance of public awareness and psychosocial care for children and their respective families.

Keywords

Retinoblastoma; Extra-ocular; Quality of life; Abidjan; Child

Introduction

Retinoblastoma is a malignant tumor of early childhood (0 to 5 years) developed at the expense of young cells of the retina. It is a genetic disease due to the bi-allelic inactivation of the RB1 gene which is a suppressor gene and located at the level of chromosome 13 [1]. Retinoblastoma is a scarce but serious and curable pathology. Untreated or treated late, it progresses to extra-ocular retinoblastoma which is a progression of the tumor outside the eyeball, affecting the surrounding tissues or other more distant anatomical regions. It is a metastatic complication of the tumor whose most frequent sites of damage are: the bone, the bone marrow, the regional, pretragal, cervical lymph nodes and the central nervous system in the form of meningeal damage under arachnoid or more rarely intra-parenchymal [2,3]. Apart from its functional and vital prognosis, extra-ocular retinoblastoma also has a significant impact on affected patients’ life quality. According to the World Health Organization, quality of life is an individual’s perception of their place in life, in the context of the culture and value system in which they live, in relation to their goals, expectations, norms and concerns. Indeed, quality of life is a very broad concept that goes beyond that of living conditions and refers to human fulfillment, happiness, environmental health, life satisfaction and the general well-being of a society. Thus, for a child, the quality of life is above all to be and do ¨like the others¨. This cannot apply to young children and infants, for whom the notion of quality of life is generally confused with that of parents. Moreover, a child’s life quality is compromised in chronic and neoplastic pathologies, in particular extra-ocular retinoblastoma. The impact on visual acuity, the aesthetic damage, the length and heaviness of the management of this condition constitute for the affected child and his entourage, important factors of psychological stress and social disturbances. At the national level, no study has yet been carried out on the impact of extra-ocular retinoblastoma on affected patients’ life quality. It is in this context that we are therefore carrying out this work, the objective of which is to contribute to the assessment of children well-being with extra-ocular retinoblastoma in the ophthalmology and pediatric departments in collaboration with the histopathologists of Treichville’s University Hospital Center in order to improve their living conditions.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Our study was carried out jointly in the onco-ophthalmology, pediatric oncology and histopathology departments at the University Hospital Center of Treichville. It covered all the cases of extra-ocular retinoblastoma collected in the aforementioned departments.

All patients aged 0 to 15 years, received and cared for in the various departments, for extra-ocular retinoblastoma with histopathological and/or computed tomography confirmation were included.

Methods

We carried out a retrospective and cross-sectional descriptive study over 4 years on the files of patients treated from January 2013 to December 2017. The data have been collected on a standardized survey form on which a number of orders have been assigned to each patient. The survey forms have been completed by a team trained for this purpose.

In the onco-ophthalmology and onco-paediatrics departments, data was collected from patients’ follow-up records and consultation registers. Some patients were seen again for further examination. The variables studied concerned socio-demographic characteristics (gender, age, living place of patients), clinical characteristics (consultation time, treatments carried out before the consultation in our department) and treatments carried out in the departments.

Confirmation of the diagnosis has been provided by histopathological study of the enucleation and/or biopsy specimen. The analysis of the quality of life has been assessed thanks to the QUALIN questionnaire for children aged 0 to 3 years and the AUQUEI questionnaire for children aged 4 to 12 years [4]. These methods of assessing the quality of life consist in the development of questionnaires intended for parents and pediatricians for children from one year to three years old.

The different items used (0= completely false; 1= somewhat false; 2= true and false at the same time; 3= I don't know; 4= somewhat true; 5= absolutely true) resulting in a classification.

Very poor quality of life: 0 to 34

Poor quality of life: 35 to 67

Average quality of life: 68 to 102

Good quality of life: 103 to 136

As for AUQUEI Questionnaire intended for children aged 4 to 12, it follows in chronological order from the previous one, addressing children aged 4 to 12 directly. This method collects the child's point of view about various areas of everyday life and also during specific conditions (hospitalization).

The response levels are 4 in number, and are represented by faces annotated on a figure shown to the child who must, for each question, tick the face corresponding best to his feelings. Data analysis and processing were performed using Fisher, Word 2010, EPI info 7.2.0.1 and Excel 2007 tests.

For the realization of this study, we have obtained the written agreement of the various heads of department concerned as well as of the Medical and Scientific Direction of the University Hospital Center. Furthermore, we have no conflict of interest in carrying out this study.

Results

Epidemiological characteristics

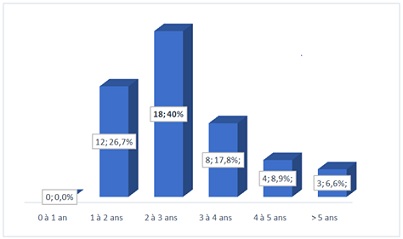

Our work identified 45 cases of extra-ocular retinoblastoma during the study period. The annual hospital frequency was evaluated at 9 cases per year. The mean age of patients at the time of diagnosis is 35.5 months with extremes ranging from 22 months to 166 months with an average time to diagnosis of 12.2 months (ranging from 4 to 48 months). The age group from 1 to 5 years was the most represented with 42 patients (93.4%). The age groups are distributed in figure 1. A peak frequency is found between 2 and 3 years with 18 patients or 40%. There was a male predominance with a sex ratio of 1.4. The average patient follow-up was 6.5 months with the extremes ranging from 02 weeks to 13 months. Most of patients lived outside Abidjan, i.e. 29 patients (64.44%). Parents employed in the informal sector predominated, i.e. 26 fathers (57.8%) and 16 mothers out of 45 (35.6%). We also found a high proportion of mothers with no profession, 17 cases (37.8%). We observed only 8 civil servant fathers (17.8%) for 2 civil servant mothers (4.4%) and 3 fathers (6.6%) for 2 mothers (4.4%) working in the private sector (table 1). Patients residing outside Abidjan had recourse, before admission, to medical treatment in 1 case against 9 for those in Abidjan and traditional treatment in 24 cases against 6 for residents in Abidjan. 30 patients (67%) out of 45 used traditional treatment.

Figure 1: Distribution of patients by age group.

Figure 1: Distribution of patients by age group.

|

|

Parents |

|

|

Occupation |

Father |

Mother |

|

Civil servant |

8 (17.8%) |

2 (4.4%) |

|

Informal sector |

26 (57.8%) |

16 (35.6%) |

|

Private sector |

3 (6.6%) |

2 (4.4%) |

|

Pupil/students |

0 |

1 (2.2%) |

|

No occupation |

1 (2.2%) |

17 (37.8%) |

|

Total |

38 (100%) |

38 (100%) |

Table 1: Repartition by parent’s profession.

Clinical aspects

The distribution according to the international ABC classification showed that on admission, most of patients were in the very advanced stages of the disease, i.e. 43 cases (96%) at stage E and 2 cases (4%) at stage D. 45 patients, 41 (91.1%) had retinoblastoma extension to the optic nerve with at least one metastatic location.

Therapeutic aspects

Patients living outside Abidjan used, before admission, medical treatment in 1 case against 9 for those in Abidjan and traditional treatment in 24 cases against 6 for residents in Abidjan. Enucleation was performed in 19 cases (42.2%). Chemotherapy was performed in 34 patients (75.6%) according to different modalities: neoadjuvant in 5 patients (11.1%), adjuvant in 3 patients (6.7%) and palliative in 19 patients (42.2%) However, 7 patients (15.6%) received mixed adjuvant and neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Only 2 patients (4.4%) received treatment with adjuvant radiotherapy.

Child’s life quality

Poor quality of life was found in 36 cases (80%) for 02 cases of average quality of life and 7 undefined cases. The proportion of poor quality of life was identical (50%) in both sexes. It was in significant proportion in 24 patients (66.7%) living outside Abidjan against 12 (33.3%) living in Abidjan. At the end of the follow-up, we listed 7 patients lost to follow-up out of 45.

All children with an age below 36 months have a greater poor quality of life at 72.2%. An average quality of life was also found in some patients aged 3 years and over (Table 2, Figure 2).

|

Quality of life |

||||

|

Age range (Months) |

Good |

Average |

Bad |

Not mentioned |

|

12 to 24 |

0 |

0 |

12 (33.3%) |

0 |

|

25 to 36 |

0 |

0 |

14 (38.9%) |

4 (57.1%) |

|

37 to 49 |

0 |

0 |

6 (16.6%) |

2 (28.6%) |

|

49 to 60 |

0 |

2 (100%) |

2 (5.6%) |

0 |

|

> 60 |

0 |

0 |

2 (5.6%) |

1 (14.3%) |

|

Total |

0 |

2 (100%) |

36 (100%) |

7 (100%) |

Table 2: Distribution of quality of life by age.

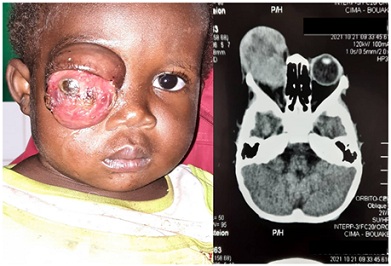

Figure 2: Unilateral retinoblastoma in a 3-year-old girl in the onco-ophthalmology department of the University Hospital of Treichville.

Figure 2: Unilateral retinoblastoma in a 3-year-old girl in the onco-ophthalmology department of the University Hospital of Treichville.

Quality of life was low in patients who received enucleation combined with chemotherapy and radiotherapy. All patients who received no treatment and those who underwent enucleation alone had a poor quality of life.

The 36 (100%) children in stage E had a poor quality of life and the 02 patients in stage D had an average quality of life. Concerning the poor quality of life, patients who received chemotherapy alone represented the highest proportion, i.e. 61.1%, followed by those who received the combination of chemotherapy and enucleation, i.e. 27.8%.

Discussion

The average age of our patients was 35.5 months with extremes of 22 months to 166 months. This average age is consistent with those of Berété in Abidjan and Togo in Mali who respectively found an average age of 54.6 months and 50 months for a consultation and diagnosis time of more than 12 months [5,6]. The long delay in consultation would explain the late age of diagnosis of retinoblastoma as well as the high number of extra ocular forms in underdeveloped countries. Thus Selistre in Brazil, with a relatively short diagnostic delay (5.4 months), had an earlier mean age of diagnosis (18.1 months) for extra-ocular forms [7]. Shorter delays were noted in the USA and Tunisia where Brutos and Chebbi [8,9] found 2.5 months (0 to 22 months) and 5.6 months (0 to 30 months) respectively. This finding shows that in low-income countries, the diagnosis of retinoblastoma is made at a late stage.

Extra ocular retinoblastoma has had a significant impact on the quality of life of children and their families. Indeed, the socio-economic conditions of the parents of the patients remain modest in several African studies.

We listed 57.8% of fathers and 35.6% of mothers of patients working in the informal sector with only 17.8% of fathers working as civil servants and 37.8% of mothers being unemployed. Our study reveals a socio-economic level that was generally low. Unfavorable socio-economic conditions were also noted in Niger by Abba who specified that 94.7% of patients had a low socio-economic level [10]. The association of the low socio-economic level of our patients with the lack of medical coverage is all factors that would contribute to increased use of traditional healers.

Poor quality of life was found in 80% of cases in our study. This could be explained by the low socio-economic level of the populations in Côte d'Ivoire. Our study showed high percentages of fathers working in the informal sector (57.8%), mothers with no profession (37.8%). Only 17.8% of fathers and 4.4% of mothers were civil servants. This socio-professional situation in our work reflects the low financial income of the parents. Thus, access to care becomes difficult to achieve due to the high cost of treatment, the cost of the management of an extra-orbital form would be estimated at 917,635.26 Francs CFA or 1349.85 Euros [11] according to the work of Lukamba et al. The median cost of treatment for retinoblastoma would be 1,216,365 CFA Francs ($1,954) per patient [12]. The quality of life of the child is therefore influenced by the inaccessibility to adequate care. In addition, in our study, patients residing outside Abidjan had the highest frequency of poor quality of life 66.7% compared to those residing in Abidjan 33.3%. This poor quality of life among children living outside Abidjan is due to the low socio-economic level, the distance from specialized health centers, ignorance of retinoblastoma’s signs at the onset stage, linked to the lack of awareness of the population and the lack of awareness at their level.

Our patients aged less than 36 months (3 years) at diagnosis had a higher frequency of poor quality of life compared to those aged between 36 to 60 months (3 to 5 years). It was respectively at 72.2% and 22.2%. On the other hand, patients older than 60 months (5 years) had a poor quality of life at 5.6%. The severity of the disease being linked to the age of onset would explain the high percentage of poor quality of life in the youngest.

Our series found poor quality of life in identical proportions in both sexes (50%).

This result would reflect that gender is therefore not a criterion for measuring the quality of life of a patient suffering from retinoblastoma. Most of patients were seen at very advanced stages of the disease, at stage E in 96% of cases and 4% at stage D. This predominance of stage E was also noted by Parrilla-Vallejo et al. [13] in a recent clinical study carried out in Spain on retinoblastoma. As in our series, Lukusa et al. noted that 90% of their patients were diagnosed at the metastases stage. Our patients underwent unilateral enucleation in 42.2% of cases. The low enucleation score in our study could be explained by the refusal of the patients, the unavailability of the operating room, the high rate of loss of sight with 15.6% and the too advanced stage of the disease.

Also the socio-cultural problems related to the loss of an eye, poverty and the misinformation of the parents would be at the origin of the long delays between the moment of the diagnosis and the acceptance of the surgical act. Enucleation and chemotherapy are the therapeutic methods used in developing countries, particularly in black Africa, due to the still too late diagnosis and especially the insufficiency of the technical platform.

Chemotherapy performed in most of our patients 75.6% could be beneficial by prolonging the life of these. However, it influences the quality of life of patients because of these many side effects. The undesirable effects of chemotherapy are very diverse and are mainly manifested by digestive, hematological, cutaneous and skin appendages disorders. Thus, there was a high percentage of poor quality of life in patients who received chemotherapy alone, i.e. 97.2%. Although this therapy contributes significantly to the management of malignant tumors, in particular extra ocular retinoblastoma, the fact remains that it causes many inconveniences that hinder the patient's life quality.

Conclusion

Retinoblastoma is a malignant tumor of the retina whose life prognosis is still bleak in developing countries. Diagnosed late in most cases, it progresses outside the eyeball corresponding to its extra-ocular form making all the seriousness of this affection. To improve it, the awareness of the population and health personnel, both medical and paramedical, is essential. For, they must serve as the first relay between patients and specialists. Associated to these arguments we can quote the lack of social security for the poorest, the under-equipment of reception centers, which are all factors complicating the medical management of patients. This management requires multidisciplinary collaboration as well; the lack of onco-ophthalmologists, pediatric oncologists, child psychiatrists, ocularists and psychologists makes the task even more difficult.

References

- Desjardins L, Putterman M (1991) Tumors of the retina, Encycl Med chir (Elsevier Masson, Paris), Ophthalmology, 21249-A30.

- Shields CL, Shields JA, Baez KA, Cater J, De Potter PV (1993) Choroidal invasion of retinoblastoma: metastatic potential and clinical risk factors. Br J Ophthalmol 9: 544-548.

- Sant M, Capocaccia R, Badioni V; UROCARE Working Group (2001) Survival for retinoblastoma in Europe. Eur J Cancer 37: 730-735.

- Berete CR, Ouffoue G, Kouakou KS (2014) Evaluation of retinoblastoma at the University Hospital of Treichville from 1995 to 2012: retrospective study of 115 cases. Biomedical Africa 19: 12-20.

- Ravens-Siebere U, Auquier P, Siméoni MC (2006) Quality of life. Cofemer 2006:157-190.

- Boubacar T, Fatou S, Fousseyni T, Mariam S, Fatoumata DT, et al. (2010) A 30- month prospective study on the treatment of retinoblastoma in the Gabriel Toure Teaching Hospital. Br J Ophthalmol 94: 467-469.

- Selistre SG, Maestri MK, Santos-Sylva P, Schüler-Faccini L, Guimarães LSP, et al. (2016) Retinoblastoma in a pediatric moncology reference center in Southern Brazil. BMC Pediatrics 16: 2-9.

- Brutos JL, Abrahamson DH, Dunked IJ (2002) Delayed Diagnosis of Retinoblastoma: Analysis of Degree, Cause, and Potential Consequences. Pediatrics 109: 45.

- Chebbi A, Bouguila H, Boussaid S, Ben Aleya N, Zgholi H, et al. (2014) Clinical profile of retinoblastoma in Tunisia. J Fr Ophthalmol 237: 442-448.

- Abba KHY, Sylla F, Ali MH, Amza A (2016) The particularities of retinoblastoma in Niger. Eur Sci 12: 1857-7881.

- Dos Santos D (2015) Cost study on the management of retinoblastoma in Mali, GCCA.

- Lukamba RM, Yao JA, Kabesha TA, Budiongo AN, Monga BB, et al. (2018) Retinoblastoma in Sub-Saharan Africa: Case Studies of the Republic of Côte d’Ivoire and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Journal of Global Oncology 4: 1-8.

- Parrilla-Vallejo M, Perea-Pérez R, Relimpio-López I, Montero-de-Espinosa I, Rodríguez-de-la-Rúa E, et al. (2018)Retinoblastoma: the importance of early diagnosis. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol (Engl Ed) 9: 423-433.

Citation: Diomandé GF, Kouassi C, Sirima DM, Yao AJJ, Doumbia A, et al. (2022) Quality of Life of Patients with Extra-Ocular Retinoblastoma in Abidjan. J Ophthalmic Clin Res 9: 105.

Copyright: © 2022 Diomandé GF, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.