Journal of Obesity & Weight Loss Category: Medical

Type: Research Article

Chocolate Consumption and Health Beliefs and its Relation to BMI in College Students

*Corresponding Author(s):

Charles PlatkinNutrition And Food Science Program, School Of Urban Public Health, Hunter College, City University Of New York School Of Public Health, Silberman Building, 2180 Third Avenue RM 528, New York, NY 10035, United States

Ming-Chin Yeh

Nutrition And Food Science Program, School Of Urban Public Health, Hunter College, City University Of New York School Of Public Health, Ilberman Bldg, 2180 Third Avenue, RM 614, New York, NY 10035, United States

Tel:+1 2123967776,

Email:myeh@hunter.cuny.edu

Received Date: Nov 06, 2015

Accepted Date: Jan 06, 2016

Published Date: Jan 21, 2016

Abstract

Objective: To evaluate chocolate consumption, its association with Body Mass Index (BMI), and the relationship between health beliefs about chocolate and its consumption in college students.

Methods: In 2013, a paper and electronic survey was conducted to assess personal health information, type of chocolate consumed, its typical serving size, and frequency of consumption. A series of statements pertaining to chocolate consumption and health was assessed using a five-point Likert scale. The survey was conducted between May 1 and August 5, 2013 and recruited participants from a multi-ethnic population of students and employees of an urban college.

Results: Participants (n=553) were 66.7% female, mean age of 23.75 years (SD=7.40) and a mean BMI of 23.61 (SD=5.11). Milk chocolate was consumed by 40% of participants and 28.4% consumed dark chocolate. Most respondents ate a small-medium or medium-large serving size of chocolate (66.8%) and consumed chocolate several times a week (48.9%). A significant association was observed with milk chocolate consumed in large serving sizes, whereas dark chocolate was consumed in small serving sizes (p=0.001). In comparison to males, females were more likely to have consumed dark chocolate (p<0.001) and in smaller servings sizes (p<.001). Racial/ethnic differences were observed with Whites consuming more dark chocolate and other racial/ethnic groups consuming more milk chocolate (p<0.001), while African-Americans and Asians consumed larger serving sizes (p=0.013). Most respondents agreed with a statement that dark chocolate is the healthiest chocolate (74.1%), this belief was stronger among females as compared to males (p<.001). While most chocolate health beliefs were similar between genders and racial and ethnic groups, males, African-Americans, and Hispanics held stronger beliefs that all chocolate is good for one’s health (p<.05). BMI was not associated with chocolate consumption nor was health beliefs about chocolate.

Conclusion: Our findings showed that this group of college-aged students tended to consume milk chocolate most commonly. Racial/ethnic and gender differences were observed in consumption and general health beliefs of chocolate. No association was observed between BMI and type of chocolate consumption, or between BMI and chocolate health beliefs.

Methods: In 2013, a paper and electronic survey was conducted to assess personal health information, type of chocolate consumed, its typical serving size, and frequency of consumption. A series of statements pertaining to chocolate consumption and health was assessed using a five-point Likert scale. The survey was conducted between May 1 and August 5, 2013 and recruited participants from a multi-ethnic population of students and employees of an urban college.

Results: Participants (n=553) were 66.7% female, mean age of 23.75 years (SD=7.40) and a mean BMI of 23.61 (SD=5.11). Milk chocolate was consumed by 40% of participants and 28.4% consumed dark chocolate. Most respondents ate a small-medium or medium-large serving size of chocolate (66.8%) and consumed chocolate several times a week (48.9%). A significant association was observed with milk chocolate consumed in large serving sizes, whereas dark chocolate was consumed in small serving sizes (p=0.001). In comparison to males, females were more likely to have consumed dark chocolate (p<0.001) and in smaller servings sizes (p<.001). Racial/ethnic differences were observed with Whites consuming more dark chocolate and other racial/ethnic groups consuming more milk chocolate (p<0.001), while African-Americans and Asians consumed larger serving sizes (p=0.013). Most respondents agreed with a statement that dark chocolate is the healthiest chocolate (74.1%), this belief was stronger among females as compared to males (p<.001). While most chocolate health beliefs were similar between genders and racial and ethnic groups, males, African-Americans, and Hispanics held stronger beliefs that all chocolate is good for one’s health (p<.05). BMI was not associated with chocolate consumption nor was health beliefs about chocolate.

Conclusion: Our findings showed that this group of college-aged students tended to consume milk chocolate most commonly. Racial/ethnic and gender differences were observed in consumption and general health beliefs of chocolate. No association was observed between BMI and type of chocolate consumption, or between BMI and chocolate health beliefs.

INTRODUCTION

Since 1980, the worldwide prevalence of overweight and obesity has almost doubled [1]. Overweight and obesity has been attributed to 3.4 million deaths per year worldwide [2] and an increased risk of chronic diseases [1]. As a result, much attention has been paid to prevention mechanisms, including increasing physical activity and adequate nutrition. The impact of dietary components, such as chocolate products, on body weight and health status is being actively researched.

Chocolate consumption and health status

In recent years, chocolate-related research, especially in regards to the health benefits of dark chocolate, has grown in popularity [3-6]. Although most research highlights the benefits of chocolate consumption, it is important to note the difference between commercially available chocolates. Chocolate, a processed form of cocoa beans derived from the seeds of Theobroma cacao, is a suspension of sugar, cocoa, and/or milk solids in a continuous fat phase, which is categorized primarily into white, milk or dark chocolate that differ on a spectrum of chocolate liquor [7]. White chocolate has no chocolate liquor, dark chocolate has the most chocolate liquor, and milk chocolate varies in between [8]. Additionally, chocolate is a rich source of polyphenols, such catechins, and flavonol glycosides [9], as well as a source of minerals and compounds like methylxanthines that add to its health-promoting properties [10,11].

There have been many studies indicating the cardiovascular benefits associated with consumption of dark chocolate and its flavonoids. In a randomized controlled crossover trial, Faridi et al., [4] examined the cardio protective effects of solid dark chocolate and liquid cocoa and found that its consumption improved endothelial function and decreased blood pressure in overweight adults. Similarly, other studies have demonstrated that consuming 50 g of dark chocolate significantly improved endothelial function, increased nitric oxide levels, and decreased superoxide anion production [5,6]. In a related study pertaining to cardiovascular health, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) family heart study found an inverse association between the frequency of chocolate consumption and the calcified atherosclerotic plaque in the coronary arteries [3]. Furthermore, meta-analyses of studies have found that dark chocolate and cocoa beverages decreased systolic blood pressure by 2.77 to 4.5 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure by 2.20 to 2.50 mmHg [12,13].

Cocoa and its polyphenols have been shown to prevent or slow down the progression of cancer by diminishing intracellular reactive oxygen species production, enhance the activity of endogenous antioxidant enzymes, act as a radical scavengers, prevent oxidative damage to DNA, inhibit inflammatory mediators, and induce apoptosis in cancer cells [14]. For instance, cocoa was shown to be chemo protective as it induced antioxidant enzymes and suppressed the expression of inflammatory mediators in a mouse model of colitis-associated cancer cells [15]. Another study found that a polyphenolic cocoa extract had an antioxidant effect at the molecular level by over expressing a gene, CYP1A1, in breast cancer cells which is important in metabolizing xenobiotics, carcinogens, and estrogen [16].

There is some evidence that dark chocolate may help with body fat or body weight. For example, an animal study found that mice that were fed a high-fat diet supplemented with an equivalent reasonable human dose of cocoa had a lower increase in fat mass compared to the high-fat control group [17]. In another study examining the anti-obesity effects of cocoa in rats found that cocoa decreased body weight gain and the weight of white adipose tissue [18].

Although there have been an abundance of research focusing on the health contributions of chocolate, it is important to note that not all varieties offer the same benefits. Milk chocolate and, especially, white chocolate are higher in fat, calories, and added sugars in comparison to dark chocolate, thus may reduce healthful effects. A prospective cohort study found a dose-dependent relationship between chocolate-candy consumption and weight gain in women with each additional 1 oz serving per month associated with an average weight gain of 0.92 kg in the three-year study period [19]. Furthermore, there is also research that addresses its potential adverse contributions to health. A study of older women aged 70-85 years of age that examined the relationship between chocolate consumption and bone density and strength found that a higher frequency of consumption was associated with lower bone density and strength [20].

Due to the controversy and inconsistencies in prior research, a study that assesses the relationship between BMI and chocolate consumption, differentiating between different types, is warranted. In addition, the study will explore if health beliefs affect chocolate consumption and BMI. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine such relationship. The objectives of this study will be to evaluate: 1) chocolate consumption in college students, 2) their association with BMI, 3) the relationship between health beliefs about chocolate and their consumption.

There have been many studies indicating the cardiovascular benefits associated with consumption of dark chocolate and its flavonoids. In a randomized controlled crossover trial, Faridi et al., [4] examined the cardio protective effects of solid dark chocolate and liquid cocoa and found that its consumption improved endothelial function and decreased blood pressure in overweight adults. Similarly, other studies have demonstrated that consuming 50 g of dark chocolate significantly improved endothelial function, increased nitric oxide levels, and decreased superoxide anion production [5,6]. In a related study pertaining to cardiovascular health, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) family heart study found an inverse association between the frequency of chocolate consumption and the calcified atherosclerotic plaque in the coronary arteries [3]. Furthermore, meta-analyses of studies have found that dark chocolate and cocoa beverages decreased systolic blood pressure by 2.77 to 4.5 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure by 2.20 to 2.50 mmHg [12,13].

Cocoa and its polyphenols have been shown to prevent or slow down the progression of cancer by diminishing intracellular reactive oxygen species production, enhance the activity of endogenous antioxidant enzymes, act as a radical scavengers, prevent oxidative damage to DNA, inhibit inflammatory mediators, and induce apoptosis in cancer cells [14]. For instance, cocoa was shown to be chemo protective as it induced antioxidant enzymes and suppressed the expression of inflammatory mediators in a mouse model of colitis-associated cancer cells [15]. Another study found that a polyphenolic cocoa extract had an antioxidant effect at the molecular level by over expressing a gene, CYP1A1, in breast cancer cells which is important in metabolizing xenobiotics, carcinogens, and estrogen [16].

There is some evidence that dark chocolate may help with body fat or body weight. For example, an animal study found that mice that were fed a high-fat diet supplemented with an equivalent reasonable human dose of cocoa had a lower increase in fat mass compared to the high-fat control group [17]. In another study examining the anti-obesity effects of cocoa in rats found that cocoa decreased body weight gain and the weight of white adipose tissue [18].

Although there have been an abundance of research focusing on the health contributions of chocolate, it is important to note that not all varieties offer the same benefits. Milk chocolate and, especially, white chocolate are higher in fat, calories, and added sugars in comparison to dark chocolate, thus may reduce healthful effects. A prospective cohort study found a dose-dependent relationship between chocolate-candy consumption and weight gain in women with each additional 1 oz serving per month associated with an average weight gain of 0.92 kg in the three-year study period [19]. Furthermore, there is also research that addresses its potential adverse contributions to health. A study of older women aged 70-85 years of age that examined the relationship between chocolate consumption and bone density and strength found that a higher frequency of consumption was associated with lower bone density and strength [20].

Due to the controversy and inconsistencies in prior research, a study that assesses the relationship between BMI and chocolate consumption, differentiating between different types, is warranted. In addition, the study will explore if health beliefs affect chocolate consumption and BMI. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine such relationship. The objectives of this study will be to evaluate: 1) chocolate consumption in college students, 2) their association with BMI, 3) the relationship between health beliefs about chocolate and their consumption.

METHODOLOGY

Study design and survey development

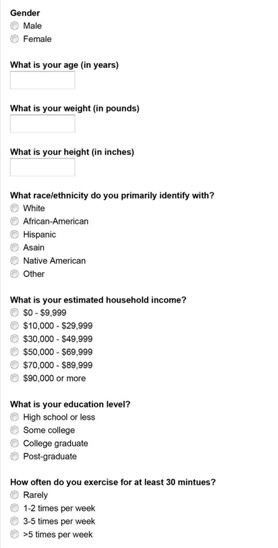

The Institutional Review Board for the protection of human participants in research at Hunter College, City University of New York approved the protocol for this study, which was conducted in 2013. Survey questions were developed based primarily on prior studies [21-23]. Prior to data collection, a pilot test of 30 participants was conducted to assess the survey quality. Minimal changes were made to the survey, mainly in regards to wording of questions. For example, since some responses identified more than one ethnicity, a “mixed ethnicity” choice was added. The survey was designed to assess personal health information, chocolate consumption and chocolate health beliefs. The survey was divided into three separate sections:

Individual characteristics and attributes

Questions in this section included age, sex, ethnicity, height and weight, household income and health-seeking behavior questions such as smoking status, degree of physical activity and self-perceived healthy eating habits. Self-reported height and weight were used to calculate BMI.

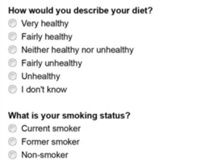

Chocolate consumption and health beliefs

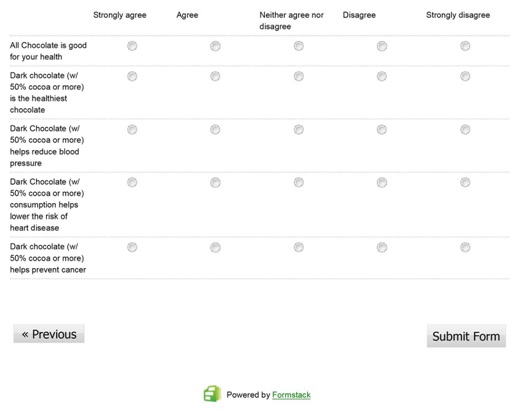

Questions in this section pertained to type of chocolate consumed (i.e., milk chocolate, dark chocolate, white chocolate or any type), typical serving size based on pictures provided, frequency of consumption, and which chocolate-containing foods are consumed (i.e., candy, cake, ice cream, etc.). This was followed by a series of statements pertaining to chocolate consumption and health assessed by a five-point Likert scale ranging from strongly agrees to strongly disagree.

Data collection

The survey was conducted between May 1 and August 5, 2013 and recruited participants from a multi-ethnic population of students and employees of an urban college in New York City. Research assistants approached students and employees in the dining area and halls to complete a paper survey and verbal consent was obtained from each participant. In addition, an online version of the survey (Appendix 1), was created using Formstack (www.formstack.com), a website dedicated to form creation and online data collection tool. A link to the survey and consent form was distributed to students using listserv emails to different academic departments within the college.

Statistical analysis

General descriptive statistics (Mean/SD and percentages) were used to describe the sample and assess chocolate consumption. Chi-square tests were conducted to test for differences in chocolate consumption between males and females and race/ethnic groups (White, African-American, Hispanic, Asian, and Other/Mixed). Pair wise comparisons were conducted using chi-square goodness-of-fit tests. Differences in five chocolate health beliefs assessed were evaluated using chi-square test for categorical outcomes (agree/strongly agree vs. neither agree nor disagree vs. disagree/strongly disagree). Results from these analyses were then confirmed using Mann-Whitney U and Kruskal-Wallis tests for the original 5-Likert scales.

Lastly, linear and logistic regressions were conducted to test for associations between BMI index and BMI categories and chocolate consumption and chocolate health beliefs. All analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, version 12, SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, 2004). Significance was judged as p<.05 and analyses were not adjusted for inflated Type I error due to testing multiple hypotheses.

Lastly, linear and logistic regressions were conducted to test for associations between BMI index and BMI categories and chocolate consumption and chocolate health beliefs. All analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, version 12, SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, 2004). Significance was judged as p<.05 and analyses were not adjusted for inflated Type I error due to testing multiple hypotheses.

RESULTS

Sample description

The sample was representative of current college undergraduate students [24] (Table 1). Of the respondents, 66.7% were female. The mean age was 23.75 years (SD=7.40). Most identified themselves as White (35.3%), followed by Asian (22.8%), Hispanic (19.4%), other/mixed (14.1%) and African American (8.3%). The mean BMI was 23.61 (SD=5.11). The majority of respondents were of normal BMI (66.1%), 17.1% were overweight, and 9.60% were obese. Most respondents described their diet as healthy (57.0%) and reported exercising at least 1 times a week (64.6%).

| Characteristic | n | M (SD) or % |

| Age | 551 | 23.75 (7.40) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 182 | 32.7 |

| Female | 371 | 66.7 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | 195 | 35.3 |

| African-American | 46 | 8.3 |

| Asian | 126 | 22.8 |

| Hispanic | 107 | 19.4 |

| Other/Mixed | 78 | 14.1 |

| Household Income | ||

| $0 - $29,999 | 174 | 32.8 |

| $30,000 - $49,999 | 126 | 23.8 |

| $50,000 - $69,999 | 80 | 15.1 |

| $70,000 or more | 150 | 28.3 |

| Education Level | ||

| Some college | 365 | 66 |

| College graduate | 188 | 34 |

| BMI | 519 | 23.61 (5.11) |

| Underweight (BMI<18.5) | 37 | 7.1 |

| Normal (18.5≤BMI≤24.9) | 343 | 66.1 |

| Overweight(25≤BMI≤29.9) | 89 | 17.1 |

| Obese(MBI ≥30) | 50 | 9.6 |

| Smoking Status | ||

| Non smoker | 443 | 79.7 |

| Former smoker | 60 | 10.8 |

| Current smoker | 51 | 9.2 |

| Exercise | ||

| Rarely | 130 | 35.4 |

| 1-2 times per week | 102 | 27.8 |

| 3 or more times per week | 135 | 36.8 |

| Diet | ||

| Healthy | 306 | 57 |

| Neither healthy nor unhealthy | 146 | 27.2 |

| Unhealthy | 85 | 15.8 |

Chocolate consumption

About 40% of the respondents reported consuming milk chocolate, followed by dark chocolate (28.4%, with the vast majority consuming dark chocolate with cocoa level of over 50%), and any type of chocolate (28.6%). Most respondents (66.8%) typically ate a small-medium or a medium-large size of chocolate and 48.9% consumed chocolate several times a week (Table 2). There was a statistically significant association between the type of chocolate consumed and serving size (χ2(6, N=442)= 21.50, p=0.001), with milk chocolate more often consumed in large serving sizes as compared to dark chocolate (23.4% vs. 12.3%). Majority of respondents reported consuming multiple products containing chocolate (72.3%), most often candies and cookies.

| Overall n=494 | Male n=182 | Female n=371 | White n=195 | White n=195 | Hispanic n=107 | Asian n=126 | Other/ Mixed n=78 | |||

| % | % | % | p-valuec | % | % | % | % | % | p-valued | |

| Don’t eat chocolate | 7.3 | 8 | 6.7 | 0.128 | 3.8 | 17.8 | 5.5 | 10.8 | 5.7 | 0.369 |

| Type of chocolate usually consumed | <.001 | <.001 | ||||||||

| Milk chocolate | 43 | 43.8 | 45.2 | 35.7 | 71.4 | 53 | 40.7 | 50 | ||

| Dark chocolatea | 28.4 | 18.5 | 34.4 | 40.9 | 11.4 | 21.7 | 31.4 | 15.6 | ||

| Any typeb | 28.6 | 37.7 | 20.4 | 23.4 | 17.1 | 25.3 | 27.9 | 34.4 | ||

| Typical serving size | <.001 | 0.013 | ||||||||

| Small | 14.6 | 10 | 17 | 18.9 | 18.9 | 12.8 | 11 | 9.1 | ||

| Small-medium | 40.8 | 33.3 | 44.4 | 45.7 | 27 | 41.9 | 28.6 | 53 | ||

| Medium-large | 26 | 30 | 23.9 | 22.9 | 32.4 | 23.3 | 35.2 | 19.7 | ||

| Large | 18.6 | 26.7 | 14.7 | 12.6 | 21.6 | 22.1 | 25.3 | 18.2 | ||

| Frequency of chocolate eating | 0.585 | 0.081 | ||||||||

| Daily | 4 | 4 | 3.6 | 3.5 | 2.8 | 5.8 | 0 | 9.1 | ||

| Several times a week | 48.9 | 45.6 | 50.8 | 53.8 | 38.9 | 46.5 | 53.3 | 39.4 | ||

| Rarely | 47.1 | 50.3 | 45.5 | 42.8 | 58.3 | 47.7 | 46.7 | 51.5 |

aDark chocolate includes dark chocolate with 50% cocoa or more and less than 50% cocoa

bIncludes White chocolate

c, dp-values for gender differences and race/ethnic differences were based on bivariate 2x2 χ² tests. Pair wise comparisons for race/gender differences were assessed using the χ² goodness-of-fit tests. Significant differences (p < .05) are bolded.

bIncludes White chocolate

c, dp-values for gender differences and race/ethnic differences were based on bivariate 2x2 χ² tests. Pair wise comparisons for race/gender differences were assessed using the χ² goodness-of-fit tests. Significant differences (p < .05) are bolded.

Females were significantly more likely to consume dark chocolate (34.4% vs. 18.5%) and less likely to choose any type of chocolate (20.4% vs. 37.7%) than males (χ²(2, N=440)= 19.60, p<0.001). Likewise, females consumed smaller servings of chocolate overall (small/small-medium serving size 61.4% vs. 43.3%, χ²(3, N=456)= 15.59, p<.001). Chocolate preferences also differed by race/ethnicity, with Whites consuming significantly more dark chocolate than African Americans, Hispanic and Other/Mixed (40.9% vs. 11.4%, 21.7% and 15.6%, respectively; χ²(4, N=129)= 106.23, p<0.001). Milk chocolate consumption was significantly associated with being African-American (71.4% vs. 35.7% for Whites, 53.0% for Hispanics, 50.0% for Other/Mixed and 40.7% for Asians; χ2(4, N=197)= 19.52, p<0.001). In addition, African-Americans and Asians reported consuming generally larger serving sizes (χ²(12, N=455)= 25.33, p=0.013) (Table 2). There was no association between chocolate type, serving size or chocolate consumption frequency and respondent’s BMI.

Health beliefs about chocolate and chocolate consumption

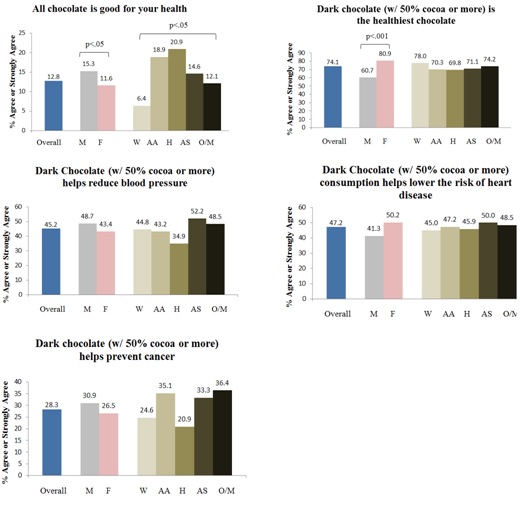

Overall, most respondents agreed with a statement that dark chocolate (with 50% cocoa or more) is the healthiest chocolate (74.1%). About half of respondents reported a belief that dark chocolate (w/ 50% cocoa or more) helps reduce blood pressure (45.7%) and dark chocolate (w/ 50% cocoa or more) consumption helps lower the risk of heart disease (47.2%). Thirteen percent of respondents thought that all chocolate are good for one’s health and 28.3% endorsed a statement that dark chocolate (with 50% cocoa or more) helps prevent cancer.

Chocolate health beliefs regarding blood pressure, heart disease, and cancer were similar among females and males and racial/ethnic groups (Figure 1). However, males, African-Americans, and Hispanics reported a stronger belief that all chocolate is good for your health (χ²(2, N=451)= 8.99, p=0.011 and χ²(8, N=450)= 21.91, p=0.005, respectively) (Figure 1). In addition, women were significantly more likely to agree that dark chocolate (with 50% cocoa or more) is the healthiest chocolate (χ²(2, N=453)= 21.44, p<0.001). There were no differences in chocolate health beliefs and neither chocolate consumption patterns nor respondent’s BMI.

Chocolate health beliefs regarding blood pressure, heart disease, and cancer were similar among females and males and racial/ethnic groups (Figure 1). However, males, African-Americans, and Hispanics reported a stronger belief that all chocolate is good for your health (χ²(2, N=451)= 8.99, p=0.011 and χ²(8, N=450)= 21.91, p=0.005, respectively) (Figure 1). In addition, women were significantly more likely to agree that dark chocolate (with 50% cocoa or more) is the healthiest chocolate (χ²(2, N=453)= 21.44, p<0.001). There were no differences in chocolate health beliefs and neither chocolate consumption patterns nor respondent’s BMI.

Figure 1: Beliefs about chocolate overall and by gender and race/ethnicity.

Note: M=Male; F=Female; W=White; AA=African-American; H=Hispanic; AS=Asian; O/M=Other/Mixed; Gender differences and race/ethnic differences were based on bivariate 2x2 χ² tests.

DISCUSSION

Chocolate consumption, chocolate health beliefs, and BMI

The majority of participants consumed milk chocolate, followed by dark chocolate, in small-medium to medium-large servings several times a week. We found an association between types of chocolate consumed and serving size; dark chocolate was consumed in smaller servings compared to other types of chocolate, while milk chocolate was consumed in larger serving sizes. Randomized crossover trials have found that dark chocolate in smaller servings can be more satiating than milk chocolate and curb sweet cravings longer [25,26]. Moreover, another study found that smelling or ingesting 30 g of dark chocolate suppresses the appetite through the involvement of decreased ghrelin, the hunger hormone [27]. However, dark chocolate’s effect on satiety might be a function of its intense flavor from its high cocoa content and high fat content that increases gastrointestinal transit time [28].

Women have been reported to have more cravings for chocolate and are more likely to choose chocolate as a “comfort food” compared to men [29]. In this study, females were found to be significantly more likely to consume dark chocolate and in smaller servings. Contrastingly, a randomized controlled study that examined the psychoactive effects of tasting chocolate and the components to desire more consumption revealed that more men than women desired to consume more chocolate in spite of men’s lower chocolate craving and liking scores [30]. On the other hand, a cross-sectional study of undergraduate psychology students found no gender differences in chocolate consumption [31].

We also observed significant differences in chocolate consumption among racial/ethnic groups. Dark chocolate consumption was greater among Whites and milk chocolate consumption greater among other racial/ethnic groups with Asians and African-Americans consuming the largest sizes. Milk chocolate is known to be considerably sweeter and less bitter than dark chocolate. Although there may be many factors to explain this finding, a study that examined sucrose preferences reported racial/ethnic differences with African-Americans preferring solutions with higher concentrations of sucrose compared to Whites [32].

We found that most participants believed that dark chocolate to be the healthiest choice, to help reduce blood pressure, and to lower the risk of heart disease. And overall, chocolate health beliefs did not differ between participants in most statements. However, this study did find gender and racial differences concerning chocolate’s health beliefs with males, African-Americans, and Hispanics reporting a stronger belief in all chocolate being good for one’s health and with females agreeing that dark chocolate is the healthiest choice. Our findings contradict the suggestion that chocolate, treated as a treat, has limited credibility of any health claims among its participants [33].

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the relationship between the type of chocolate consumption or chocolate health beliefs and BMI. We found that neither chocolate consumption nor type of chocolate is correlated to BMI category. The relationship between chocolate consumption and BMI in the current literature, however, is mixed. A meta-analysis found no significant relationship between BMI and flavonoid-rich cocoa in 11 short-term studies [34]. Cross-sectional surveys have found those who consumed chocolate at higher frequencies had lower levels of BMI [35-37]. However, those authors did mention BMI-confounding factors such as physical activity [35,36]. A prospective study yielded a significant dose-response association between chocolate intake and BMI over time, but their cross-sectional analysis found an inverse association between chocolate intake and BMI [38].

Women have been reported to have more cravings for chocolate and are more likely to choose chocolate as a “comfort food” compared to men [29]. In this study, females were found to be significantly more likely to consume dark chocolate and in smaller servings. Contrastingly, a randomized controlled study that examined the psychoactive effects of tasting chocolate and the components to desire more consumption revealed that more men than women desired to consume more chocolate in spite of men’s lower chocolate craving and liking scores [30]. On the other hand, a cross-sectional study of undergraduate psychology students found no gender differences in chocolate consumption [31].

We also observed significant differences in chocolate consumption among racial/ethnic groups. Dark chocolate consumption was greater among Whites and milk chocolate consumption greater among other racial/ethnic groups with Asians and African-Americans consuming the largest sizes. Milk chocolate is known to be considerably sweeter and less bitter than dark chocolate. Although there may be many factors to explain this finding, a study that examined sucrose preferences reported racial/ethnic differences with African-Americans preferring solutions with higher concentrations of sucrose compared to Whites [32].

We found that most participants believed that dark chocolate to be the healthiest choice, to help reduce blood pressure, and to lower the risk of heart disease. And overall, chocolate health beliefs did not differ between participants in most statements. However, this study did find gender and racial differences concerning chocolate’s health beliefs with males, African-Americans, and Hispanics reporting a stronger belief in all chocolate being good for one’s health and with females agreeing that dark chocolate is the healthiest choice. Our findings contradict the suggestion that chocolate, treated as a treat, has limited credibility of any health claims among its participants [33].

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the relationship between the type of chocolate consumption or chocolate health beliefs and BMI. We found that neither chocolate consumption nor type of chocolate is correlated to BMI category. The relationship between chocolate consumption and BMI in the current literature, however, is mixed. A meta-analysis found no significant relationship between BMI and flavonoid-rich cocoa in 11 short-term studies [34]. Cross-sectional surveys have found those who consumed chocolate at higher frequencies had lower levels of BMI [35-37]. However, those authors did mention BMI-confounding factors such as physical activity [35,36]. A prospective study yielded a significant dose-response association between chocolate intake and BMI over time, but their cross-sectional analysis found an inverse association between chocolate intake and BMI [38].

LIMITATIONS

Findings from this study are limited to urban, young college students and extrapolation of the results to the rest of the US population is limited. Furthermore, there is a chance of misreporting of chocolate consumption by participants that may have biased associations. Food recalls can be subject to variation in recalling in certain food items such as a snack items like chocolate, respondents more likely to omit than add food items, and over- or underestimate portion sizes [39]. Although some studies have shown that the self-reported body weight and heights of young adults tend to be fairly accurate [40,41], another limitation can be the possibility of underestimation of self-reported weight and overestimation of height [42,43]. Another limitation of the study can be the lack of accurate labeling of polyphenols in commercial chocolate to determine the true relationship between chocolate and health or BMI. Lastly, there may be relevant confounding factors, such as energy intake or physical activity, which may be responsible for the relationship between chocolate consumption with BMI.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, majority of the participants consumed milk chocolate in larger serving sizes, followed by dark chocolate in smaller serving sizes. The gender and racial/ethnic differences observed was dark chocolate consumption being significantly greater among Whites and females. Participants tended to disagree with chocolate health belief statements, but males, African-Americans, and Hispanics believed strongly all chocolate is good for one’s health, while females believed dark chocolate is the healthiest. There was no association between BMI and type of chocolate consumption, or between BMI and chocolate health beliefs. Further research should take steps to control confounding factors, such as physical activity or energy intake, to confirm whether the type of chocolate consumption and BMI are not related.

REFERENCES

- World Health Organization (2014) Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2014. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, Danaei G, Shibuya K, et al. (2012) A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990-2010: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet 380: 2224-2260.

- Djoussé L, Hopkins PN, Arnett DK, Pankow JS, Borecki I, et al. (2011) Chocolate consumption is inversely associated with calcified atherosclerotic plaque in the coronary arteries: The NHLBI family heart study. Clin Nutr 30: 38-43.

- Faridi Z, Njike VY, Dutta S, Ali A, Katz DL (2008) Acute dark chocolate and cocoa ingestion and endothelial function: a randomized controlled crossover trial. Am J Clin Nutr 88: 58-63.

- Nanetti L, Raffaelli F, Tranquilli AL, Fiorini R, Mazzanti L, et al. (2012) Effect of consumption of dark chocolate on oxidative stress in lipoproteins and platelets in women and in men. Appetite 58: 400-405.

- Nogueira LdP, Knibel MP, Torres MRSG, Neto JFN, Sanjuliani AF (2012) Consumption of high-polyphenol dark chocolate improves endothelial function in individuals with stage 1 hypertension and excess body weight. International Journal of Hypertension 2012: 1-9.

- Afoakwa EO, Paterson A, Fowler M (2007) Factors influencing rheological and textural qualities in chocolate-a review. Trends in Food Science & Technology 18: 290-298.

- US Food and Drug Administration. (2015) Cacao Products. In: Food for human consumption, Food and Drug Administration, Food and Drugs. CFR - Code of Federal Regulations Title 21, Department Of Health And Human Services, US Food and Drug Administration, USA.

- Wollgast J, Anklam E (2000) Review on polyphenols in Theobroma cacao: Changes in composition during the manufacture of chocolate and methodology for identification and quantification. Food Research International 33: 423-447.

- 1Jalil AM, Ismail A (2008) Polyphenols in cocoa and cocoa products: is there a link between antioxidant properties and health? Molecules 13: 2190-2219.

- Torres-Moreno M, Torrescasana E, Salas-Salvadó J, Blanch C (2015) Nutritional composition and fatty acids profile in cocoa beans and chocolates with different geographical origin and processing conditions. Food Chemistry 166: 125-132.

- Desch S, Schmidt J, Kobler D, Sonnabend M, Eitel I, et al. (2010) Effect of cocoa products on blood pressure: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Hypertens 23: 97-103.

- Ried K, Sullivan TR, Fakler P, Frank OR, Stocks NP (2012) Effect of cocoa on blood pressure. Cochrane, London, UK.

- Martin MA, Goya L, Ramos S (2013) Potential for preventive effects of cocoa and cocoa polyphenols in cancer. Food Chem Toxicol 56: 336-351.

- Pandurangan AK, Saadatdoust Z, Hamzah H, Ismail A (2015) Dietary cocoa protects against colitis-associated cancer by activating the Nrf2/Keap1 pathway. BioFactors 41: 1-14.

- Oleaga C, García M, Solé A, Ciudad CJ, Izquierdo-Pulido M, et al. (2012) CYP1A1 is overexpressed upon incubation of breast cancer cells with a polyphenolic cocoa extract. Eur J Nutr 51: 465-476.

- Dorenkott MR, Griffin LE, Goodrich KM, Thompson-Witrick KA, Fundaro G, et al. (2014) Oligomeric cocoa procyanidins possess enhanced bioactivity compared to monomeric and polymeric cocoa procyanidins for preventing the development of obesity, insulin resistance, and impaired glucose tolerance during high-fat feeding. J Agric Food Chem 62: 2216-2227.

- Matsui N, Ito R, Nishimura E, Yoshikawa M, Kato M, et al. (2005) Ingested cocoa can prevent high-fat diet-induced obesity by regulating the expression of genes for fatty acid metabolism. Nutrition 21: 594-601.

- Greenberg JA, Manson JE, Buijsse B, Wang L, Allison MA, et al. (2015) Chocolate-candy consumption and 3-year weight gain among postmenopausal US women. Obesity (Silver Spring) 23: 677-683.

- Hodgson JM, Devine A, Burke V, Dick IM, Prince RL (2008) Chocolate consumption and bone density in older women. Am J Clin Nutr 87: 175-180.

- California Department of Public Health (2012) Compendium of surveys - For nutrition Education and Obesity Prevention. Research and Evaluation Section, Network for a Healthy California, California Department of Public Health, California, USA.

- Gámbaro A, Ellis AC (2012) Exploring consumer perception about the different types of chocolate. Braz J Food Technol 15: 317-324.

- Parmenter K, Wardle J (1999) Development of a general nutrition knowledge questionnaire for adults. Eur J Clin Nutr 53: 298-308.

- Hunter College (2012) Table 14: Undergraduate students profile, fall 2007 to fall 2012. Hunter College, New York, USA.

- Akyol A, Dasgin H, Ayaz A, Buyuktuncer Z, Besler HT (2014) β-Glucan and dark chocolate: a randomized crossover study on short-term satiety and energy intake. Nutrients 6: 3863-3877.

- Sørensen LB, Astrup A (2011) Eating dark and milk chocolate: a randomized crossover study of effects on appetite and energy intake. Nutr Diabetes 1: 21.

- Massolt ET, van Haard PM, Rehfeld JF, Posthuma EF, van der Veer E, et al. (2010) Appetite suppression through smelling of dark chocolate correlates with changes in ghrelin in young women. Regul Pept 161: 81-86.

- Farhat G, Drummond S, Fyfe L, Al-Dujaili EA (2014) Dark chocolate: An obesity paradox or a culprit for weight gain? Phytother Res 28: 791-797.

- Wansink B, Cheney MM, Chan N (2003) Exploring comfort food preferences across age and gender. Physiol Behav 79: 739-747.

- Nasser JA, Bradley LE, Leitzsch JB, Chohan O, Fasulo K, et al. (2011) Psychoactive effects of tasting chocolate and desire for more chocolate. Physiol Behav 104: 117-121.

- van Gucht D, Soetens B, Raes F, Griffith JW (2014) The attitudes to chocolate questionnaire. Psychometric properties and relationship with consumption, dieting, disinhibition and thought suppression. Appetite 76: 137-143.

- Pepino MY, Mennella JA (2005) Factors contributing to individual differences in sucrose preference. Chem Senses 1: 319-320.

- Lalor F, Kennedy J, Wall PG (2011) Impact of nutrition knowledge on behaviour towards health claims on foodstuffs. British Food Journal 113: 753-765.

- Shrime MG, Bauer SR, McDonald AC, Chowdhury NH, Coltart CE, et al. (2011) Flavonoid-rich cocoa consumption affects multiple cardiovascular risk factors in a meta-analysis of short-term studies. J Nutr 141: 1982-1988.

- Cuenca-García M, Ruiz JR, Ortega FB, Castillo MJ, HELENA study group (2014) Association between chocolate consumption and fatness in European adolescents. Nutrition 30: 236-239.

- Golomb BA, Koperski S, White HL (2012) Association between more frequent chocolate consumption and lower body mass index. Arch Intern Med 172: 519-521.

- Strandberg TE, Strandberg AY, Pitkälä K, Salomaa VV, Tilvis RS, et al. (2008) Chocolate, well-being and health among elderly men. Eur J Clin Nutr 62: 247-253.

- Greenberg JA, Buijsse B (2013) Habitual chocolate consumption may increase body weight in a dose-response manner. PLoS One 8: 70271.

- Serdula MK, Alexander MP, Scanlon KS, Bowman BA (2001) What are preschool children eating? A review of dietary assessment. Annu Rev Nutr 21: 475-498.

- Kuczmarski MF, Kuczmarski RJ, Najjar M (2001) Effects of age on validity of self-reported height, weight, and body mass index: Findings from the third national health and nutrition examination survey, 1988-1994. J Am Diet Assoc 101: 28-34.

- Quick V, Byrd-Bredbenner C, Shoff S, White AA, Lohse B, et al. (2015) Concordance of self-report and measured height and weight of college students. J Nutr Educ Behav 47: 94-98.

- Pursey K, Burrows TL, Stanwell P, Collins CE (2014) How accurate is web-based self-reported height, weight, and body mass index in young adults? J Med Internet Res 16: 4.

- Yoong SL, Carey ML, D’Este C, Sanson-Fisher RW (2013) Agreement between self-reported and measured weight and height collected in general practice patients: A prospective study. BMC Med Res Methodol 13: 13-38.

APPENDIX

Citation: Ming-Chin Yeh, Platkin C, Estrella P, MacShane C, Allinger D, et al. (2016) Chocolate Preferences and Its Relation to BMI and Health Status in College Students. J Obes Weight Loss 1: 004.

Copyright: © 2016 Charles Platkin, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Journal Highlights

© 2026, Copyrights Herald Scholarly Open Access. All Rights Reserved!