Inactivation of Type I IFN Jak-STAT Pathway in EBV Latency

*Corresponding Author(s):

Ling WangDepartment Of Internal Medicine, Center Of Excellence For Inflammation, Infectious Diseases And Immunity, Quillen College Of Medicine, East Tennessee State University, Tennessee, United States

Tel:+1 4234398063,

Fax:+1 4234397010

Email:wangl3@etsu.edu

Abstract

Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) latent infection is associated with a variety of lymphomas and carcinomas. Interferon (IFN) Regulatory Factors (IRFs) are a family of transcription factors, among which IRF7 is the “master” regulator of type I IFNs (IFN-I) that defends against invading viruses. Robust IFN-I responses require a positive feedback loop between IRF7 and IFN-I. In recent years, we have discovered that IRF7 is significantly induced and activated by the principal EBV oncoprotein--Latent Membrane Protein 1 (LMP1); however, IRF7 fails to trigger robust IFN-I responses in EBV latency. We believe this intriguing finding is critical for EBV latency and oncogenesis, yet the underlying mechanism of this paradoxical phenomenon remains unclear. It is well known that tyrosine phosphorylation of most components of the IFN-I Jak-STAT pathway is essential for its signaling transduction. Thus, we have performed phosphotyrosine proteomics. We have found that the IFN-I Jak-STAT pathway is inactive due to the attenuated STAT2 activity, whereas the IFN-II Jak-STAT pathway is constitutively active, in EBV latency. We further confirmed these results by immunoblotting. This pilot study provides valuable information for the critical question regarding how the IRF7-mediated IFN-I response is evaded by EBV in its latency, and will prompt us to elucidate the underlying mechanisms.

INTRODUCTION

Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) is of increasing medical importance as it is the etiologic agent in various lymphomas and carcinomas [1-2]. It is now generally accepted that EBV causes, modifies, or contributes to the genesis of more malignancies than any other tumor virus does [3].

The Interferon Regulatory Factor (IRF) family of transcription factors plays pivotal roles in the regulation of multiple facets of host defense system, among which IRF7 is the “master” regulator of type I Interferon (IFN-I) response to pathogenic infection [4]. Robust IFN-I response during infection requires a positive feedback loop between IRF7 and IFN-I [5-6]. Aberrant production of IFN-I, however, is associated with autoimmune disorders and malignancies [7-9]. Thus, tight regulation of IRF7 is important in balancing the appropriate immune response to clear invading pathogens while preventing immune-mediated pathogenesis [10].

IFNs exert their functions through induction of IFN-Stimulated Genes (ISGs) via Jak-STAT pathways [11-13]. The IFN-I Jak-STAT pathway comprises of IFNAR1/2, Jak1, Tyk2, STAT1/2, and IRF9 [14]. Following IFN-I binding to IFNARs, signaling via protein kinases leads to tyrosine phosphorylation and activation of IFNAR1 at Y466 [15], Tyk2(Y1054/Y1055) and Jak1(Y1034/Y1035), and then to that of STAT1(Y701) and STAT2(Y690 and S287) [16]. The phosphorylated STAT1/2 then dimerize and associate with IRF9 to form a complex termed interferon-stimulated gene factor 3 (ISGF3). ISGF3 translocates to the nucleus and binds to the IFN Stimulated Response Element (ISRE) to activate the transcription of ISGs [12,17-19]. In type II IFN (IFNγ) Jak-STAT pathway, Jak2 is auto phosphorylated at Y1007/Y1008 in response to IFNγ, and STAT1 is phosphorylated at both Y701 and S727. Phosphorylated STAT1 then forms a homodimer termed IFNγ-Activated Factor (GAF), which migrates into the nucleus and binds to the IFNγ-Activated Sequence (GAS) to transactivate the target ISGs.

Recent studies have shown that the IFN-I Jak-STAT signaling pathway plays a dual role in viral infection. At the early stage of infection, robust IFN-I response leads to a potent antiviral activity; meanwhile, it facilitates the establishment and maintenance of persistent infection by inducing the immune exhaustion program [20-21]. Therefore, regulation of IFN signaling is pivotal for persistent viruses, as the outcomes not only shape the immune response to infection and contribute to the establishment of persistent infection, but also affect aspects of host cell proliferation and malignancy. Notably, resistance to IFN-mediated antiviral treatment of malignancies is a problematic clinical issue, for which the underlying mechanism is not fully understood [22-24]. Indeed, viruses have developed diverse strategies to counteract IFN (IFN-I and-II) Jak-STAT signaling pathways [25-28]. However, only limited regulators for the Jak-STAT pathways in mammalians have been discovered including the SOCS, SHP, and PIAS families [29-32], primarily due to the lack of the application of high throughput screen strategies. Most of these regulators were originally identified in Drosophila [30].

To understand how EBV evades IRF7-mediated IFN-I response in its latency, in this study, we have performed phosphotyrosine proteomics, and found that IFN-I Jak-STAT pathway is impaired due to attenuated STAT2 activity. Our results also suggest that several other Jak-STAT pathways, including IFN-II Jak-STAT pathway, are active in EBV latency.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines

DG75 (EBV-), Akata (Type I), Namalwa (Type I), Daudi (Type 3 without LMP1), IB4 (Type 3 LCL), P3HR1 (Type 3 without LMP1), and JiJoye (Type 3) cells are human B cell lines. These cells were cultured in RPMI1640 medium plus 10% FBS and antibiotics. All cell culture supplies were purchased from Life Technologies.

Phosphotyrosine proteomics

Global profiling of tyrosine phosphorylation associated with EBV infection was performed by cell signaling technology. Whole cell lysates from IB4 were digested, and phosphorylated peptides were enriched with IgG control or the antibody p-Tyr-100 (Catalog # 8954) that recognizes the motif XyX. LTQ-Orbitrap-Velos LC-MS/MS was performed, and MS/MS spectra were evaluated against Homo sapiens FASTA database (NCBI), using SEQUEST 3G and the SORCERER 2 platform from Sage-N Research (v4.0, Milpitas CA), with a 5% default false positive rate to filter the results. Duplicate runs have been performed.

Immunoblotting

Cells were lysed with NP40 lysis buffer, and cell lysates were subjected to immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. Signals were detected with an Enhanced Chemiluminescence (ECL) kit following the manufacturer’s protocol (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Phospho-STAT1(Y701) (catalog # 9171), Phospho-STAT2(Y690) (catalog# 4441), and STAT1(catalog # 9172) antibodies were purchased from cell signaling technology. LMP1 antibody (CS1-4) was from Dako. IRF7 (catalog# SC-74472), STAT2 (catalog # SC-476), and GAPDH antibodies were from Santa Cruz.

Results And Discussion

Tyrosine phosphorylation of almost all the components in both the IFN-I/II Jak-STAT pathways including IFN receptors, Jaks, Tyk2, and STATs is necessary for signaling transduction upon IFN stimulation. Thus, phosphotyrosine proteomics is a powerful tool to detect the activity of Jak-STAT pathways [16]. To check if the IFN-I and IFN-II Jak-STAT pathways are deregulated in EBV latent infection, we have taken phosphotyrosine proteomics to profile global tyrosine phosphorylation in the EBV-transformed lymphoblastoid cell line IB4. As shown in table 1, we detected activating tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT1(Y701) and Jak1(Y1034/Y1035) (for both IFN-I and IFN-II pathways), as well as IFNGR1(Y304) and Jak2(Y1007/Y1008) (for IFN-II pathway only). However, activating tyrosine phosphorylation of the other three components in the IFN-I JAK-STAT pathway, including IFNAR1(Y466), STAT (Y690) or Tyk2(Y1054/Y1055), were not detected. Although IFNGR1(Y304) has not yet been documented to be required for activating the IFN-II signaling, it has been frequently detected in cancers by Mass spectrometry. In addition, our results show that STAT3, STAT4, and STAT5 are also active in EBV latency. These results suggest that the IFN-I Jak-STAT pathway is inactive, but the IFN-II Jak-STAT pathway and probably a few other Jak-STAT pathways are constitutively active, in EBV latency.

| Component | Intensity | Tyrosine Site | Peptide identified |

| IFNGR1 | 274,598 | 304 | Y*VSLITSYQPFSLEK |

| IFNGR1 | 280,266 | 304; 311 | Y*VSLITSY*QPFSLEK |

| STAT1 | 584,201 | 701 | EAPEPMELDGPKGTGY*IK |

| STAT3 | 433,965 | 539; 539; 539 | LLGPGVNY*SGCQITWAK |

| STAT3 | 33,177 | 704 | YCRPESQEHPEADPGAAPY*LK |

| STAT3 | 80,391 | 705; 705 | YCRPESQEHPEADPGSAAPY*LK |

| STAT4 | 1,522,430 | 693 | GDKGY*VPSVFIPISTIR |

| STAT5A | 101,007 | 683 | LGDLSYLIYVFPDRPKDEVFSKYY*TPVLAK |

| STAT5A,B | 1,938,120 | 694; 699 | AVDGY*VKPQIK |

| STAT6 | 468,441 | 829 | LLLEGQGESGGGSLGAQPLLQPSHY*GQSGISM#SHMDLR |

| JAK1 | 159,479 | 1030; 1035 | AIET*DKEYY*TVKDDRDSPVFWYAPECLM#QSK |

| JAK1 | 433,328 | 1030; 1048 | AIET*DKEYYTVKDDRDSPVFWY*APECLM#QSK |

| JAK1 | 584,795 | 1034 | AIETDKEY*YTVKDDRDSPVFWYAPECLMQSK |

| JAK1 | 159,479 | 1034; 1035 | AIETDKEY*Y*TVKDDRDSPVFWYAPECLM#QSK |

| JAK1 | 159,479 | 1034; 1043 | AIETDKEY*YTVKDDRDS*PVFWYAPECLM#QSK |

| JAK1 | 72,091 | 1035 | AIETDKEYY*TVKDDRDSPVFWYAPECLM#QSK |

| JAK1 | 73,514 | 598 | THIY*SGTLM#DYKDDEGTSEEK |

| JAK2 | 114,887 | 1007 | VLPQDKEY*YKVKEPGESPIFWYAPESLTESK |

| JAK2 | 62,639 | 1008 | VLPQDKEYY*K |

| JAK2 | 271,716 | 570 | REVGDY*GQLHETEVLLK |

Table 1: Deregulated activity of the Jak-STAT pathway components in EBV latency program III

Asterisks (*) indicate that the left Y is phosphorylated; pound signs (#) indicate oxidized methionine. Sites with underlined fonts indicate that the sites are responsible for activation of the corresponding components.

Consistent with our findings, EBV LMP1 has been shown to negatively regulate Tyk2 phosphorylation and the IFN-I signaling [33], and to activate STAT3 and -5 in EBV latency [34-35]. It has also been reported that Jak1, STAT1 and STAT3, but not STAT2 and STAT5, are constitutively tyrosine phosphorylated in LCL cells derived from PTLD patients [36], and STAT3 has also been reported to be constitutively active in EBV-associated immune competent patients [37]. STAT1 and Jak3 phosphorylation and activation are triggered by LMP1 [38]. However, Jak3 phosphorylation was not detected in our MS high throughput analysis.

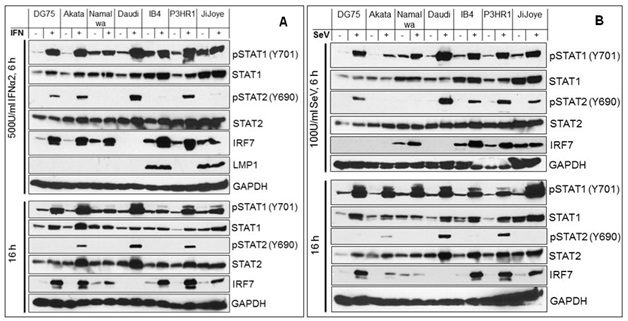

To verify the deregulation of the IFN-I Jak-STAT pathway in EBV latency, we analyzed its downstream STAT1/2 activity in EBV- and EBV+ cell lines with different latency states, including DG75 (EBV-), Akata (Type I), Namalwa (Type I), Daudi (Type 3 without LMP1), IB4 (Type 3 LCL), P3HR1 (Type 3 without LMP1), and JiJoye (Type 3) cells, in response to IFN treatment or Sendai Virus (SeV) infection (Figure 1). Phosphorylation of STAT1/2 was probed with specific phospho antibodies. The levels of STAT1 and p-STAT1 are constitutively high in cell lines with LMP1 (IB4 and JiJoye), but p-STAT2 is not readily detected in all tested cell lines (Figure 1). After 6 h of treatments, STAT2 activity is still barely detectable (Figure 1A) or significantly lower (Figure 1B) in IB4 and Jijoye cells which express high levels of LMP1. Similar results were obtained for shorter time treatments (40 min, data not shown). Namalwa is a special cell line which resembles IB4 and JiJoye in response to IFN and SeV treatments. In all other EBV-positive cell lines (except Namalwa) that do not express LMP1, STAT2 activity is readily detected after treatments. In all cell lines, STAT1 activity is still robust after the prolonged treatments (16 h), but STAT2 activity is only detected in Akata, Daudi and P3HR1 that do not express LMP1 (Figure 1). This finding is consistent with a previous report, in which STAT2 activity is detected in Daudi cells [39]. As a target gene induced by IFN-I Jak-STAT, IRF7 is generally higher in LMP1-negative cells after prolonged treatment with IFN, except IB4 (Figure 1). These observations suggest that STAT2 activity is repressed in EBV latency, and that LMP1 plays a key role in this event.

Figure 1: Attenuated IFN-I Jak-STAT pathway by targeting STAT2 activity in EBV latency.

We have provided preliminary observations here showing that EBV latent infection down regulates IFN-I Jak-STAT pathways, at least by attenuating STAT2 activity. We next will profile STAT2 regulators and evaluate the potential roles of selected regulators in EBV evasion of IRF7-mediated IFN-I response Deregulation of other Jak-STAT pathways also deserve further investigation in the setting of EBV latent infection.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the American Society of Hematology Scholar Award to SN, and in part by the NIH grant C06RR0306551. This publication is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the James H. Quillen Veterans Affairs Medical Center. The contents in this publication do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they do not have any competing interest.

REFERENCES

- Pagano JS, Blaser M, Buendia MA, Damania B, Khalili K, et al. (2004) Infectious agents and cancer: criteria for a causal relation. Semin Cancer Biol 14: 453-471.

- Angeletti PC, Zhang L, Wood C (2008) The viral etiology of AIDS-associated malignancies. Adv Pharmacol 56: 509-557.

- Sugden B (2014) Epstein-Barr virus: the path from association to causality for a ubiquitous human pathogen. PLoS Biol 12: 1001939.

- Honda K, Taniguchi T (2006) IRFs: master regulators of signalling by Toll-like receptors and cytosolic pattern-recognition receptors. Nat Rev Immunol 6: 644-658.

- Marié I, Durbin JE, Levy DE (1998) Differential viral induction of distinct interferon-alpha genes by positive feedback through interferon regulatory factor-7. EMBO J 17: 6660-6669.

- Sato M, Hata N, Asagiri M, Nakaya T, Taniguchi T, et al. (1998) Positive feedback regulation of type I IFN genes by the IFN-inducible transcription factor IRF-7. FEBS Lett 441: 106-110.

- Marshak-Rothstein A (2006) Toll-like receptors in systemic autoimmune disease. Nat Rev Immunol 6: 823-835.

- Borden EC, Sen GC, Uze G, Silverman RH, Ransohoff RM, et al. (2007) Interferons at age 50: past, current and future impact on biomedicine. Nat Rev Drug Discov 6: 975-990.

- Trinchieri G (2010) Type I interferon: friend or foe? J Exp Med 207: 2053-2063.

- Ning S, Pagano JS, Barber GN (2011) IRF7: activation, regulation, modification and function. Genes Immun 12: 399-414.

- González-Navajas JM, Lee J, David M, Raz E (2012) Immunomodulatory functions of type I interferons. Nat Rev Immunol 12: 125-135.

- Sadler AJ, Williams BR (2008) Interferon-inducible antiviral effectors. Nat Rev Immunol 8: 559-568.

- Stetson DB, Medzhitov R (2006) Type I interferons in host defense. Immunity 25: 373-381.

- Schindler C, Plumlee C (2008) Inteferons pen the JAK-STAT pathway. Semin Cell Dev Biol 19: 311-318.

- Carbone CJ, Zheng H, Bhattacharya S, Lewis JR, Reiter AM, et al. (2012) Protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B is a key regulator of IFNAR1 endocytosis and a target for antiviral therapies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 109: 19226-19231.

- Zheng H, Hu P, Quinn DF, Wang YK (2005) Phosphotyrosine proteomic study of interferonà signaling pathway using a combination of immunoprecipitation and immobilized metal affinity chromatography. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics 4: 721-730.

- Schoggins JW, Wilson SJ, Panis M, Murphy MY, Jones CT, et al. (2011) A diverse range of gene products are effectors of the type I interferon antiviral response. Nature 472: 481-485.

- Schoggins JW (2014) Interferon-stimulated genes: roles in viral pathogenesis. Curr Opin Virol 6: 40-46

- MacMicking JD (2012) Interferon-inducible effector mechanisms in cell-autonomous immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 12: 367-382.

- Wilson EB, Yamada DH, Elsaesser H, Herskovitz J, Deng J, et al. (2013) Blockade of chronic type I interferon signaling to control persistent LCMV infection. Science 340: 202-207.

- Teijaro JR, Ng C, Lee AM, Sullivan BM, Sheehan KC, et al. (2013) Persistent LCMV infection is controlled by blockade of type I interferon signaling. Science 340: 207-211.

- Zhu H, Nelson DR, Crawford JM, Liu C (2005) Defective Jak-Stat activation in hepatoma cells is associated with hepatitis C viral IFN-alpha resistance. J Interferon Cytokine Res 25: 528-539.

- Ramos JC, Ruiz P Jr, Ratner L, Reis IM, Brites C, et al. (2007) IRF-4 and c-Rel expression in antiviral-resistant adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma. Blood 109: 3060-3068.

- Kiladjian JJ, Mesa RA, Hoffman R (2011) The renaissance of interferon therapy for the treatment of myeloid malignancies. Blood 117: 4706-4715.

- Bonjardim CA, Ferreira PC, Kroon EG (2009) Interferons: signaling, antiviral and viral evasion. Immunol Lett 122: 1-11.

- Haller O, Kochs G, Weber F (2006) The interferon response circuit: induction and suppression by pathogenic viruses. Virology 344: 119-130.

- Weber F, Haller O (2007) Viral suppression of the interferon system. Biochimie 89: 836-842.

- Taylor KE, Mossman KL (2013) Recent advances in understanding viral evasion of type I interferon. Immunology 138: 190-197.

- Shuai K, Liu B (2003) Regulation of JAK-STAT signalling in the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol 3: 900-911.

- Müller P, Boutros M, Zeidler MP (2008) Identification of JAK/STAT pathway regulators--insights from RNAi screens. Semin Cell Dev Biol 19: 360-369.

- Starr R, Hilton DJ (1999) Negative regulation of the JAK/STAT pathway. Bioessays 21: 47-52.

- Ivashkiv LB, Donlin LT (2014) Regulation of type I interferon responses. Nat Rev Immunol 14: 36-49.

- Geiger TR, Martin JM (2006) The Epstein-Barr virus-encoded LMP-1 oncoprotein negatively affects Tyk2 phosphorylation and interferon signaling in human B cells. J Virol 80: 11638-11650.

- Vaysberg M, Lambert SL, Krams SM, Martinez OM (2009) Activation of the JAK/STAT pathway in Epstein Barr Virus + -associated post transplant lymphoproliferative disease: Role of Interferon- g American Journal of Transplantation 9: 2292-2302.

- Chen H, Hutt-Fletcher L, Cao L, Hayward SD (2003) A positive autoregulatory loop of LMP1 expression and STAT activation in epithelial cells latently infected with Epstein-Barr virus. J Virol 77: 4139-4148.

- Nepomuceno RR, Snow AL, Robert BP, Krams SM, Martinez OM (2002) Constitutive activation of Jak/STAT proteins in Epstein-Barr virus-infected B-cell lines from patients with posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder. Transplantation 74: 396-402.

- Chen H, Lee JM, Zong Y, Borowitz M, Ng MH, et al. (2001) Linkage between STAT regulation and Epstein-Barr virus gene expression in tumors. J Virol 75: 2929-2937.

- Gires O, Kohlhuber F, Kilger E, Baumann M, Kieser A, et al. (1999) Latent membrane protein 1 of Epstein-Barr virus interacts with JAK3 and activates STAT proteins. EMBO J 18: 3064-3073.

- Salamon D, Adori M, Ujvari D, Wu L, Kis LL, et al. (2012) Latency type-dependent modulation of Epstein-Barr virus-encoded latent membrane protein 1 expression by type I interferons in B cells. J Virol 86: 4701-4707.

Citation: Citation: Ning S, Wang L (2016) Inactivation of Type I IFN Jak-STAT Pathway in EBV Latency. J Cancer Biol Treat 3: 009.

Copyright: © 2016 Shunbin Ning , et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.