Narrative Medicine, Intensive Care and Burn Out

*Corresponding Author(s):

Enzo PrimeranoDepartment Of Anesthesia And Intensive Care, Polyclinic Of Monza, Monza, Italy

Tel:+39 338 5838446,

Email:enzoprim@alice.it

Abstract

Introduction: Narrative Medicine puts the individual at the centre of the therapeutic relationship. It is a powerful tool to improve the collaboration between the patient and those who care for them. In addition narrative medicine, which is based on specific communication skills, allows healthcare professionals to reflect on the meaning of their profession. Intensive care unit is a department with strong relational pressures. This pression influences the actions of the professionals involved. The source of stress affects the way it is managed. One of the fields of application of narrative medicine is the assessment of perceived stress by health professionals. The purpose of our study was to investigate the well-being of healthcare staff in intensive care through a narrative approach.

Materials and methods: The study was based on the voluntary participation of healthcare staff in two multi- purpose intensive therapies. Each subject had to write a fairy tale on a semi-structured basis anonymously. The structure of fairy tale was created with a particular focus on themes that could highlight burn out phenomena. The stories were read by two separate contacts who then confronted each other by analyzing clusters. In the end, the results were presented to all those who participated.

Results: We collected thirty-eight stories. All the stories followed the date track. They were full of details, colors and characters. At the beginning of the stories they talked about separation but gradually they arrive at a respectful coexistence. The words and the recurring feelings were analyzed generating a cloud. The common trace was the positive propensity for the future. When we presented our results emerged a good match between the descriptions reported and the emotions that had been described. All participants were available to carry out further projects of narrative medicine.

Conclusions: Intensive care doctors and nurses work in difficult, often conflicting environments. Despite their continued exposure to emotional conflicts, they may have difficulty expressing their feelings. This is an additional risk to develop burnout.

Narrative medicine becomes a new model for reflecting on their profession and learning to talk about their inner world. Narrative medicine becomes a therapeutic act and often correlates with other forms of expression that help to recompose the painful fragments of a disease on oneself and on the relationship with the outside world.

Keywords

Burnout; Intensive care; Narrative medicine

INTRODUCTION

Rita Charon called “narrative medicine” that part of applied medicine that integrates evidence based medicine with respect to the human side of the patient. Doctor and patient are the two sides of the same coin because they are united by the treatment process. However, the patient is often considered a puzzle of objective data, devoid of his individuality and needs. Narration offers the possibility of contextualizing clinical data. We could therefore define narrative medicine as “reinforced” medicine. The ultimate goal of narrative medicine is to improve the effectiveness of the interpersonal relationship and, therefore, treatment. Narrative skills can also be applied in the relationship with colleagues [1]. Narrative Medicine is a tool helpful to improve the relationship of care by placing the person at the center of every health act. It directly involves patients and healthcare professionals, risk managers and all those involved in “producing” health.

The narrative, as a fundamental element in the care processes is added and integrates with the qualitative data collected by evidence based medicine, in order to ensure a global therapeutic therapeutic approach and truly oriented to the organization of care. The patient through the narrative is told and/or written in its complexity. He no longer reports only his symptoms but talks about his/her emotions, lifestyle, social context and values. Patient lays out his views on the disease and the pathway to care that has involved him, positive or negative, giving health professionals the opportunity to modify processes and procedures for really taking care of him/her.

Narrative medicine is an intervention methodology based on a specific communicative competence [1-3]. It allows us to amplify our relational, clinical and organizational skills [4]. In this way it helps all health professionals to carefully welcome the experiences of people who live with the disease and those who care for them [5-6]. Storytelling is the fundamental tool for understanding and integrating the different views of those involved in the treatment process [7-11]. Narrative competence is necessary to listen to meanings and to respond with tools other than drug therapy alone. Narrative medicine provokes reflection. It requires a specific professionalism and creates a relationship of trust between doctor and patient without which no therapy can be effective. It is a medicine focused on the sick person, useful to health professionals to reflect on the meaning of their profession.

The narrative, however, is not only “to and from” the patient but also towards the operators. Health organizations themselves can use this powerful tool to improve internal communication between professionals, accompany organizational changes, and reduce work-related stress. For example, storytelling can provide useful indicators of burn out risk perception. Burn out is a looming spectrum especially in Intensive Care Units (ICU). ICU is a department with its peculiarities. Organizational and relational pressures influence the actions of all professional figures involved. Their work well- being therefore depends on how they deal with the stress they are subjected to. Stress is a subjective phenomenon that arises when an individual feels obliged to respond to a situation he is unable to deal with. The source of stress affects the way it is managed. One of the fields of application of narrative medicine is the assessment of perceived stress by health professionals [12-13]. The purpose of our study was to investigate the well-being of healthcare staff (doctors and nurses) in intensive care through a narrative approach. The purpose of the research was not to determine the actual context of events but to explore how individuals gave meaning to the events themselves [14-15]. The primary objective was to focus on the current situation of well-being of the staff involved in the study. We wanted to know how people perceived their needs and expectations related to intensive care working. The secondary objective was to identify, where present, individual or common elements of difficulty and / or aggregation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study, which is part of a larger project, was based on the voluntary participation of healthcare staff working in intensive care. The first step was to present the project to the operators involved in two units of two different hospitals. In a four-hour session, the principles of narrative medicine were presented through audiovisual material made available to anyone who requested it. We described the versatility of narrative medicine feasible in different contexts related to the doctor-patient relationship. Particular attention was paid to the applicability of the narrative to enforce aggregation of medical- nursing team and the prevention of burn out.

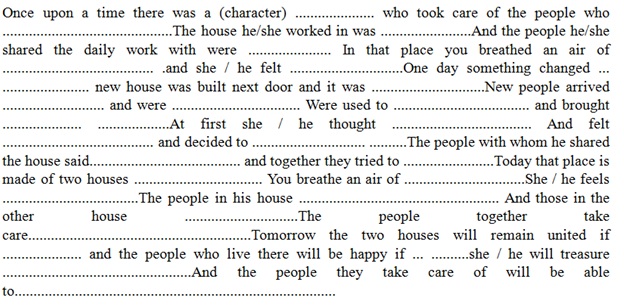

We gave each one a semi-structured written paper in the form of a fairy tale to be completed freely as desired (Figure 1). The creation of the fairy tale track was implemented by experts in narrative medicine, medical and otherwise. The track was based on the imposed construction of a new house next to that of the narrator and the arrival of its inhabitants. The structure of fairy tale was created with a particular focus on themes that could highlight burn out phenomena. The choice of the semi-structured track served to overcome the white page block of operators not prone to writing as a form of storytelling.

Figure 1: A new house next to mine.

Figure 1: A new house next to mine.

A written consent was obtained by those involved in the project and a list was created with the number of participants and their working age. All subjects had a week to complete their story. The completed fairy tales were placed in an anonymous container. At the end of the collection the stories were read by two separate contacts who then confronted each other. The readers were expert on narrative medicine. The information on the stories was integrated by analyzing clusters. We collected recurrent words or expressions to study the narrative content of the stories. We used word clouds because, in our opinion, they are an excellent support. In fact, they allow you to immediately view the key concepts. They develop visual learning and allow analysis of the linguistic and communicative strategies used in the texts. In the end, the results were presented to all those who participated.

RESULTS

We collected thirty-eight stories in a data grid showing the average working age and gender of the participants (27 women/11 men; average working age 15 years of which at least 7 in critical area). All the stories followed the date track. All were full of details, painstaking descriptions, colors and characters. The initial description of the two houses represented separate realities.

The construction of the new house was represented as the breaking of a well- established routine through the arrival of a diversity seen with suspicion at least at the beginning.

“One day something changed. The administration built a new house. The new building was built on two floors; the external facades were all white with brown shutters while each internal wall was painted in a different color as if to represent a rainbow”.

“He, observing the way of working of the colleagues of the neighboring house and afraid that his team could lose their harmony, decided to build a wall of red bricks on the border between two buildings to prevent relations between the two groups”.

Forced cohabitation, however, led to collaboration.

“His staff, however, absolutely did not agree on his choice. All together they tried to make him understand that it was important to break down that wall to share his professional method with others with reference, above all, to the solution of the related problems”.

The inhabitants of the two houses eventually overcame the mistrust described in all the stories. They learned to help each other and integrate while maintaining their individuality. This highlighted the maturity of professionals in dealing with an imposed and unwanted change.

The words, the emotions, the recurring feelings of today and the future perspectives were reported in a cloud (Figure 2). Word clouds are based on the principle of comparison and contrast. They develop collaborative thinking and creativity. The integration of adjectives, nouns or verbs that describe the atmosphere and the expectations that we have assumed size and form proportional to the frequency with which they appear in the text. The emotions found mainly were fear, sadness, irritation, loneliness, expectation and security. Recurring words were: work, respect, freedom, diversity and landmark.

Figure 2: Recurring words were: work, respect, freedom, diversity and landmark.

Figure 2: Recurring words were: work, respect, freedom, diversity and landmark.

Also present were the contrasting pairings: silence-noise, cold-hot, small-large, young- old. All the narratives brought back the words vitality and vivacity. The common trace was the positive propensity for the future. A possible future based on complicity born of an imposition. A complicity that cannot, however, is disregarded by respect for the individual.

The results therefore highlighted, in our opinion, an acute perception of stress but also an ability to adapt to it. This is probably due to a working maturity that has acted more on experience than on despair. The presentation of the results to the participants was approved, all identified in the descriptions reported. A good match emerged between the descriptions reported and the emotions that had been described. In addition, all participants were available to carry out further projects of narrative medicine.

CONCLUSION

Intensive care doctors and nurses work in difficult, often conflicting environments. They are subject to external and internal pressures [16]. Despite their continued exposure to emotional conflicts, they may have difficulty expressing their feelings. Narrative medicine is attentive to the person in its entirety. It has a holistic approach typical of unconventional medicines.

Stories told and written provide an opportunity to contextualize clinical data and allow people to read their own story with the eyes of others.

This emotional change creates a plurality of perspectives, often lacking today. We chose the fairy tale as a form of storytelling because, unlike the legend, it tells the everyday.

Daily life that can be mixed with the unusual is creating a virtual world. Anyone who writes a fairy tale can exorcise their own difficulties by mystifying them with their own imagination. So, those who read or listen, find themselves in the shoes of one of the characters who are provided with a solution by the narrator. The narrative gives the opportunity to have a different view, increasing their power of reflection.

The stories told describe an imaginary narrative centered on a track that, in the variety described, has preserved its structure. The narrative approach has allowed professionals to share feelings and opinions without superstructures except their own imagination. The analysis of the written texts allowed us to understand the culture of the subjects involved their values and their needs. Passions, personal and professional projects emerged [17-19]. In addition, anonymity has facilitated the outsourcing of deep emotions through the narration of a fairy tale. The time devoted to writing was time reserved for the unconscious export of one's own experience. Narrative medicine becomes a new model for reflecting on the profession of care, medicine and nursing, to obtain a relationship of trust that many scientific literature recognizes as an essential element for the success of treatment. In this way, professionals learn to talk about their inner world. Narrative medicine becomes a therapeutic act and often correlates with other forms of expression that help to recompose the painful fragments of a disease on oneself and on the relationship with the outside world. Storytelling has proven to be a useful tool for expressing oneself and confronting others. Proof of the fact that it represents a very strong form of communication. However, it is difficult to fit into the usual study and analysis patterns. Narrative medicine is an extraordinary tool for analysis and measurement as words have a “specific weight”. The challenge is to find criteria, methods, and tools to measure them. The limit to overcome is not to consider the narrative only words and poetry.

Words have concrete connotations, words make things happen. Words can go the same way as drugs in biochemical pathways [20]. Burn out management is not a thing of the humanization of care. It also concerns the humanization of the operator, the optimization of available resources, both human and economic. Our study was based on a not very large sample and used a qualitative approach. The results, however, suggest that the narrative approach may be an effective and relatively simple means of studying the perceptions of healthcare professionals working in intensive care.

REFERENCES

- Primerano E, Alampi D (2019) Narrative medicine in intensive care. J Anesth Clin Care 6: 43.

- Charon R (2013) Narrative medicine: caring for the sick is a work of art. JAAPA 26: 8.

- Zaharias G (2018) What is narrative-based medicine? Can Fam Physician 64: 176-180.

- Zaharias G (2018) Learning narrative-based medicine skills: Narrative-based medicine 3. Can Fam Physician 64: 352-356.

- Fioretti C, Mazzocco K, Riva S, Oliveri S, Masiero M, et al. (2016) Research studies on patient’s illness experience using the Narrative Medicine approach: a systematic review. BMJ Open 6: 011220.

- Rosti G (2017) Role of narrative-based medicine in proper patient assessment. Support Care Cancer 25: 3-6.

- Huang CD, Liao KC, Chung FT, Tseng HM, Fang JT, et al. (2017) Different perceptions of narrative medicine between Western and Chinese medicine students. BMC Med Educ 17: 85.

- Muneeb A, Jawaid H, Khalid N, Mian A (2017) The Art of Healing through Narrative Medicine in Clinical Practice: A Reflection. Perm J 21: 13-17.

- Barbieri GL, Bennati S, Capretto S, Ghinelli B, Vecchi C (2016) Imagination in narrative medicine: A case study in a children’s hospital in Italy. J Child Health Care 20: 419-427.

- Mahr G (2015) Narrative medicine and decision-making capacity. J Eval Clin Pract 21: 503-507.

- Kohn JB (2016) Stories to Tell: Conducting a Nutrition Assessment with the Use of Narrative Medicine. J Acad Nutr Diet 116: 10-14.

- Winkel AF, Feldman N, Moss H, Jakalow H, Simon J, et al. (2016) Narrative Medicine Workshops for Obstetrics and Gynecology Residents and Association With Burnout Measures. Obstet Gynecol 128: 27-33.

- Chen PJ, Huang CD, Yeh SJ (2017) Impact of a narrative medicine programme on healthcare providers’ empathy scores over time. BMC Med Educ 17: 108.

- Charon R (2001) The patient-physician relationship. Narrative medicine: a model for empathy, reflection, profession, and trust. JAMA 286: 1897-1902.

- Lewis B (2016) Mindfulness, Mysticism, and Narrative Medicine. J Med Humanit 37: 401-417.

- Vanstone M, Toledo F, Clarke F, Boyle A, Giacomini M, et al. (2016) Narrative medicine and death in the ICU: word clouds as a visual legacy. BMJ Support Palliat Care 001179.

- Saberi-Movahed AS, Waqar S, Salha A (2018) Perspectives on narrative medicine. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 13: 875-877.

- Charon R ( 2007) What to do with stories: the sciences of narrative medicine. Can Fam Physician 53: 1265-1267.

- Charon R (2004) Narrative and medicine. N Engl J Med 350: 862-864.

- Benedetti F (2018) Hope is a drug by Fabrizio Benedetti, Mondadori, Milan, Italy.

Citation: Alampi D, Primerano E (2020) Narrative Medicine, Intensive Care and Burn Out. J Anesth Clin Care 7: 48.

Copyright: © 2020 Daniela Alampi, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.