Older Men’s Experience of Weight Loss and Weight Loss Maintenance Interventions: Qualitative Findings from the Lighten Up Plus Trial

*Corresponding Author(s):

Manbinder S SidhuInstitute Of Applied Health Research, University Of Birmingham, Edgbaston, Birmingham, B15 2TT, United Kingdom

Tel:+44 01214147895,

Email:m.s.sidhu@bham.ac.uk

Abstract

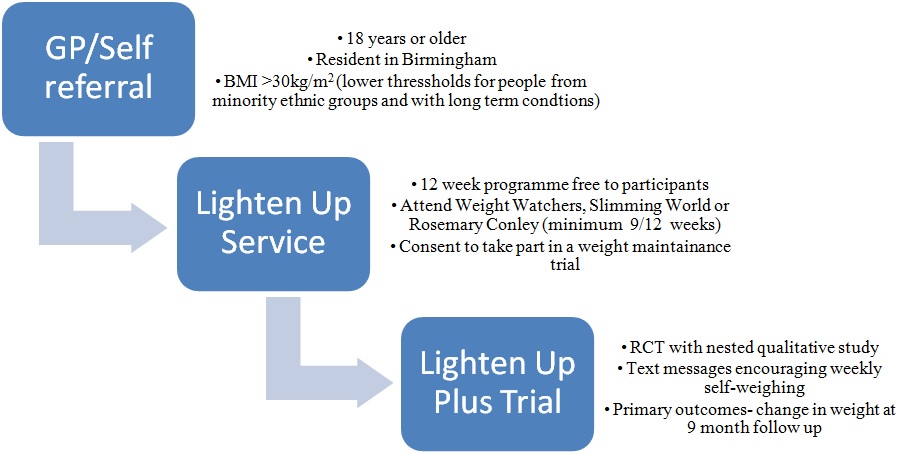

Study design: A qualitative study using semi-structured interviews nested within a Randomised Controlled Trial (RCT) delivered in the United Kingdom (UK).

Methods: Ten semi-structured interviews were completed with male participants who had completed a funded 12 week commercial weight loss programme and opted to receive continued weight management support as part of a subsequent RCT. A topic guide was used to explore attitudes about barriers and facilitators to weight management, experience of attending a commercial weight loss programme, and current strategies for maintenance. Thematic analysis was used with a constant comparison approach.

Results: Although there was little apprehension prior to attending commercial weight loss programmes, once present men felt uncomfortable and ostracised for being a minority where content and design was felt to be better suited for female attendees. Text based support was easy to use to prevent weight regain. The texts were generic and men wanted more personalisation. Participants were aware of the wider public health discourse around obesity and felt motivated to use weight management strategies, such as self-weighing, to manage their weight. Nevertheless, men required external support to encourage long term weight management.

Conclusion: Overweight and obese older men face potential conflicts when deciding to attend weight loss programmes and the nature of support they wish to receive post attendance. Men did not reject the idea of receiving text messages as a form of support, but felt it distinctly lacked personalisation compared to the face-to-face, weekly, support of being part of a group. The design, delivery and application of text based support to prevent weight regain for overweight and obese men require greater personalisation to provide long term weight management support.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Men remain a significant minority when attending weight loss programmes with high levels of attrition [8,9]; only 10% of 29326 referral courses to Weight Watchers by the National Health Service (NHS) were for men [10]. Although literature is limited on men’s experiences of attending weight loss programmes [9], many cite that content and promoted weight loss strategies, such as dieting, are better suited to women, while men demonstrate a greater preference to discuss associated health concerns [11]. Several interventions have tried to address male needs [12,13]. The SHED-IT [12] and FFIT [13] programmes were designed for male participants only, delivered in workplaces and football grounds respectively.

Whilst many studies have focused on interventions for weight loss, fewer focus on preventing weight regain and supporting weight loss maintenance in the medium to long term [14,15]. A systematic review by Dombrowski et al., concluded interventions targeting diet and physical activity in combination are effective in reducing weight regain after receiving treatment for weight loss at 12 months [16]. Specifically, research has indicated that self-weighing may be a useful method of self-monitoring for both weight loss and maintenance [17,18]. Services have been designed to support men and encourage participation in weight loss maintenance programmes; these include, but not limited to, men only groups, online material, or even pharmacist based services; yet these can be expensive, time consuming or difficult to attend due to employment commitments. A systematic review of the use of text messaging to achieve behaviour change in disease prevention and disease management has reported it as an effective tool for behaviour change [19]. We hypothesised that a technological approach to weight loss maintenance might be attractive to men, as it requires limited time and effort, while messages can prompt self-weighing in privacy as existing literature has shown men to be reluctant to be weighed in front of others owing to stigma [20].

In this study, we discuss findings from semi-structured interviews conducted with older men invited to take part in a text message weight management RCT after attending a commercial weight loss programme for 12-weeks. We focus on content and interactions with group members and facilitators of the commercial sessions, as well as views about the design, delivery and application of a text message maintenance programme that encouraged regular self-weighing. As a result, our findings add to the existing literature on men’s weight management, and whether low-cost methods, such as text messaging to promote self-weighing, are acceptable to prevent weight regain following a weight loss programme.

METHODS

Study design

| What is the Lighten Up Plus trial? | Lighten Up Plus was an RCT with participants who completed their initial weight loss programme randomly allocated to one of two weight loss maintenance programmes. |

| Who was eligible for the Lighten Up Plus trial? | Adults aged 18 years or over, who attended a minimum 9 out of 12 weeks of either Weight Watchers, Slimming World or Rosemary Conley, had been objectively weighed within the previous 2 weeks, had access to scales to weigh self, and access to a phone line (mobile or land-line). Those unable to understand English or women known to be pregnant were excluded. |

| What interventions did the Lighten Up Plus comparison groups receive? |

Usual care received a telephone conversation about weight maintenance with a member of the call centre staff plus an information sheet with tips for preventing weight regain.

|

| Could the intervention group withdraw? | Participants could withdraw from receiving text messages by replying stop. Participants could withdraw from the trial at any time. |

Access and recruitment

Sampling

| Participant | Ethnicity | Age | Occupation/employment | Past weight loss attempt | Trial group | *Pre BMI | *Post BMI |

| PT1 | White British | 76 | Retired skilled manual | Yes | Text | 36.23 | 33.46 |

| PT2 | White British | 79 | Retired skilled manual worker | Yes | Usual care | *29.14 | 28.06 |

| PT3 | White British | 67 | Semi-retired skilled manual | Yes | Text | 33.11 | 31.02 |

| PT4 | Black British | 65 | Retired professional | No | Text | *29.8 | 27.93 |

| PT5 | White British | 50 | Full time professional | Yes | Usual care | 34.15 | 31.25 |

| PT6 | White British | 62 | Semi-retired skilled manual | Yes | Text | 53.86 | 45.89 |

| PT7 | White British | 65 | Retired | Yes | Text | 41.72 | 34.21 |

| PT8 | White British | 65 | Full time semi-skilled | Yes | Usual care | 36.77 | 36.48 |

| PT9 | White British | 55 | Full time skilled | Yes | Usual care | 35.02 | 32.32 |

| PT10 | Asian British | 42 | Self-employed professional | No | Usual care | 34.53 | 32.87 |

Data collection

Interviews were completed in participant’s homes or place that was convenient to participants. Transcription was completed by OA or an external transcription company. All interviews were audio-taped and transcribed verbatim. Interviews ceased when no new concepts/themes were emerging. Participants were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time and assured that their personal details would be kept confidential. All participants were given a numerical identifier to ensure anonymity.

Statement of ethical approval

Data analysis

FINDINGS

Attending commercial weight loss programmes

“I went to a (commercial slimming group) session but I didn't feel particularly that it was going to work for me. Whether it was just that individual group, I don’t know but it didn’t feel right for me...I went to another group and that actually had a male consultant PT5.”

Predominantly, men felt that content delivered across commercial programmes was better suited to meet the perceived needs of women such as dieting and meal planning; however, men failed to describe how programmes could be better tailored:

“It was more content, I think. It was the way they were describing the meal sizes and things like that. I don’t think it was - it was more aimed towards the women losing weight in the way things were said as well PT8.”

Paramount to attending commercial programmes was interactions with other group members and the nature of discussions that took place. Gender dictated the nature of the topics discussed with group members, where losing weight by dieting to improve physical appearance appeared to be of greater importance to female attendees. Moreover, some male participants initially felt singled out from the group:

“I suppose there was a bit of embarrassment about being the male in a largely female dominated group PT5”

Evidently, men wanted to attend weight management programmes with other men to create a sense of ‘camaraderie’:

“The fact that I was one of only a couple of men [okay] I was, it’s disheartening PT10”

Clearly, men found it difficult to adapt to their minority status within group sessions. Nevertheless, many were able to build personal, friendly, and comfortable relationships with other members of the group (male and female) along with facilitators. The use of humour was used to mask the initial embarrassment of attending the programme [28]:

“cos we used to have a laugh and a joke (smiling) PT2”

For many, the continued support given by group members and facilitators provided motivation to continue with weight loss:

“It’s like you get an applaud from the group so that’s the supporting part coming in for your weight loss and even if you’ve put weight on, you still turn up PT5”

Acceptability of the design and delivery of text messages

“Just a simple question ‘What is your weight today?’ Straight forward. And I sent back what it was [weight reading], PT1.”

Sending a weekly request by text message gave participants greater control over when they chose to weigh themselves compared to group meetings. For men, the process of losing or managing their weight was a private dilemma; therefore, receiving text messages felt unobtrusive:

“I probably found it better as a text only because you can reply at your convenience whereas when they used to come through I used to be with friends or you know......it could have been an inconvenient time to take a personal call PT6.”

Yet, many participants encountered technical problems using the text messaging service with reminders sometimes received before the initial request:

“I didn’t have much of a problem as such. It’s just that texting was out of sync PT4.”

The primary drawback was the lack of personalisation. Men expressed a preference for face-to-face communication or what was described a ‘human’ approach. Furthermore, text messages failed to encourage men to make behavioural changes which led many to withdraw:

“If you hadn’t lost any weight or up a pound or whatever they would say ‘Oh, just keep trying and probably drink more water’ and I did that for about two months probably and I was getting nowhere and I thought this is a waste of time. So I just stopped PT3.”

As a result, the impersonal and detached nature of the text messaging service and the text messages left participants disenchanted with the service. Many made comparisons with commercial weight loss programmes, where they were receiving group support and weighed weekly with a facilitator.

Weight maintenance strategies

“I just be naughty and say well today I am just going to have an ‘all sins day’ and I just eat what I want as much as I want PT4.”

Nevertheless, men demonstrated a greater knowledge of dietary control with regard to purchasing reduced fat food products, reading nutritional labels, and calorie counting:

“I sort of study the labels when I buy things in supermarkets. I try and control my calorie intake on a daily basis PT7.”

Technology and interactive sources were used, giving men access to a larger of pool of information that could be personalised to support weight management. Men were able to use social media applications and websites to support better lifestyle management through online groups/forums for moral encouragement:

“I am on a close group on Facebook with members from [commercial slimming group] and if ever you are stuck for a recipe or...I mean I go on every night and see what other people are eating PT6.”

Men varied in their frequency of self-weighing without reminders from the text message intervention; those who continued to attend commercial programmes self-weighed less and preferred to receive support from the facilitator, while others who regularly self-weighed could make changes to their diet readily:

“I never used to weigh myself other than [commercial slimming group] because your scales can be totally different PT6.”

“I used to weigh myself at least weekly [okay] in fact I used to put the weight in my diary so that way I could see if I was putting on weight and if anything that was the strategy I’d compare it week by week PT10.”

Environmental considerations

“One glass of wine is fine and another wine is better and one drink is okay, it’s good for your heart or something, then it’s no, no none of that, it’s terrible mixed messages PT10.”

Issues regarding personal control over lifestyle choices were discussed; notably, men recognised the need for external support to lose weight or change their lifestyle, although they needed to take initial steps to lose weight:

“Sometimes the individual has to have a hard look at themselves and say ‘Right, what are you going to do about it?’ before the NHS starts to come on board PT5.”

All participants recognised the importance of continued support from attending commercial weight management programmes. The weight loss experienced in the first 12-weeks of attending commercial programmes had encouraged men to continue after the free consultation period had ended:

“I wanted to carry on, don’t think at the moment I will be confident enough to stop going to [commercial slimming group], that I would be able to maintain weight loss so as far as I’m concerned, I will be going for quite some time PT6.”

However, the primary barrier to continued attendance was the cost of commercial providers:

“I mean it would be lovely if [commercial slimming group] is paid for by the NHS but I can’t see that happening PT6.”

Notably, participants supported the need for commercial providers to help with weight management, and other than the cost, found them well suited to address their needs of building confidence, continued motivation, and group provision.

DISCUSSION

Our sample demonstrated a distinct awareness of wider social and cultural discourses surrounding older men attending weight loss programmes. Men acknowledged they were entering a feminine space whereby their minority status could only be addressed with the presence of more men. This highlights the importance of the ‘relationships’ aspect of the programme, particularly the interaction between participants and programme deliverers. In contrast to existing published literature [9,12], many men in our sample reported discomfort attending mixed gender programmes i.e., feeling isolated, unable to relate with female attendees with regard to weight management, and desiring greater male camaraderie. These findings support the trend that men continue to be under represented in commercial weight loss programmes [6] and cite a preference for all-male groups [9,12] which can be effective [29]. Feelings of discomfort led to men choosing not to attend their allocated programme. However, the presence of humour encouraged men to build relationships with other members of the groups and facilitators [30]. Nevertheless, these views are specific to our older male sample, who may hold stronger objections to sharing health spaces with women. In comparison to a qualitative study exploring men’s views on weight loss (mean age 37 years), older men in our sample were more likely to identify socio-environmental factors as barriers to successful weight management rather than a lack of knowledge [23,31].

The men in our sample acknowledged the importance of continued support to maintain weight loss. There appeared little or no issue with using the messaging service; registering, understanding requests, and replying to messages with a weight reading. Issues arose with the design and delivery of the service; in particular, participants received reminder text messages before the initial request for their weight, probably due to poor mobile signals. Consequently, the successfulness of encouraging participants to self-weigh was dependent upon mobile signal connectivity-ensuring the correct message was sent and received at the designated time. Yet, men showed a willingness to continue monitoring their weight-related behaviour, albeit continuing to attend weight loss providers to weigh themselves.

Our findings differ from existing literature, with men contextualising their own eating and lifestyle behaviour in light of wider cultural, social and political considerations about obesity as well as the level of personal choice they exercised. Conversely, there was recognition that ‘choices’ were the product of individual preferences combined with knowledge and provision from the NHS and/or commercial providers. Though, all recognised the need for continued weight management support.

Strengths and limitations

Policy recommendations

CONCLUSION

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

FUNDING

REFERENCES

- Butland B, Jebb S, Kopelman P, McPherson K, Thomas S, et al. (2007) Tackling Obesities: Future Choices-Project report. (2ndedn), Government Office for Science, London, UK.

- Health and Social Care Information Centre (2013) Health Survey for England. Health and Social Care Information Centre, UK.

- Health and Social Care Information Centre (2010) Health Survey for England - 2009, Health and lifestyles. Health and Social Care Information Centre, UK.

- Health and Social Care Information Centre (2012) Adult anthropometric measures, overweight and obesity. Health Survey for England 2012 1: 1-39.

- Government Office for Science Department of Health (2007) Foresight project looking at how we can respond to rising levels of obesity in the UK. In: Tackling Obesities: Future Choices. Government Office for Science and Department of Health, UK.

- Robertson C, Archibald D, Avenell A, Douglas F, Hoddinott P, et al. (2014) Systematic reviews of and integrated report on the quantitative, qualitative and economic evidence base for the management of obesity in men. Health Technol Assess 18: 1-424.

- Beardsworth A, Bryman A, Keil T, Goode J, Haslam C, et al. (2002) Women, men and food: the significance of gender for nutritional attitudes and choices. British Food Journal 104: 470-491.

- Leishman J (2007) Working with men in groups - experience from a weight management programme in Scotland. In: White A, Pettifer M (eds.). Hazardous Waist: Tackling Male Weight Problems. Radcliffe Publishing, UK. Pg: 75-86.

- Gray CM, Anderson AS, Clarke AM, Dalziel A, Hunt K, et al. (2009) Addressing male obesity: an evaluation of a group-based weight management intervention for Scottish men. J Mens Health 6: 70-81.

- Ahern AL, Olson AD, Aston LM, Jebb SA (2011) Weight Watchers on prescription: an observational study of weight change among adults referred to Weight Watchers by the NHS. BMC Public Health 11: 434.

- Sabinsky MS, Toft U, Raben A, Holm L (2007) Overweight men’s motivations and perceived barriers towards weight loss. Eur J Clin Nutr 61: 526-531.

- Morgan PJ, Lubans DR, Collins CE, Warren JM, Callister R (2011) 12-Month outcomes and process evaluation of the SHED-IT RCT: an internet-based weight loss program targeting men. Obesity 19: 142-151.

- Gray CM, Hunt K, Mutrie N, Anderson AS, Treweek S, et al. (2011) Can the draw of professional football clubs help promote weight loss in overweight and obese men? A feasibility study of the Football Fans in Training programme delivered through the Scottish Premier League. J Epidemiol Community Health 65: 37-38.

- McLean N, Griffin S, Toney K, Hardeman W (2003) Family involvement in weight control, weight maintenance and weight-loss interventions: a systematic review of randomised trials. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 27: 987-1005.

- Young MD, Morgan PJ, Plotnikoff RC, Callister R, Collins CE (2012) Effectiveness of male-only weight loss and weight loss maintenance interventions: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Obes Rev 13: 393-408.

- Dombrowski SU, Knittle K, Avenell A, Araújo-Soares V, Sniehotta FF (2014) Long term maintenance of weight loss with non-surgical interventions in obese adults: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 348: 2646.

- Burke LE, Wang J, Sevick MA (2011) Self-monitoring in weight loss: a systematic review of the literature. J Am Diet Assoc 111: 92-102.

- vanWormer JJ, French SA, Pereira MA, Welsh EM (2008) The impact of regular self-weighing on weight management: a systematic literature review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 5: 54.

- Cole-Lewis H, Kershaw T (2010) Text messaging as a tool for behavior change in disease prevention and management. Epidemiol Rev 32: 56-69.

- Ogden J, Evans C (1996) The problem with weighing: effects on mood, self-esteem and body image. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 20: 272-277.

- Denzin, NK, Lincoln YS (1994) Handbook of qualitative research. Sage Publications, London, UK.

- Salsbury J, Spencer CH, Wiggins J, Dyson L, du Plessis J et al. (2009) Weight-loss results for 2200 male patients with a BMI>29kg /m2 following the LighterLife Programme in 2008. ECO 2009, 17th European Congress on Obesity, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

- Morgan PJ, Warren JM, Lubans DR, Collins CE, Callister R (2011) Engaging men in weight loss: Experiences of men who participated in the male only SHED-IT pilot study. Obes Res Clin Pract 5: 169-266.

- Johnson F, Wardle J (2011) The association between weight loss and engagement with a web-based food and exercise diary in a commercial weight loss programme: a retrospective analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 8: 83.

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG (1985) Naturalistic inquiry. SAGE Publications, Beverly Hills, California, USA.

- Boyatzis R (1998) Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development, SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, California, USA.

- Saldana J (2009) The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researcher. Sage Publications, London, UK.

- Gillon E (2003) Can men talk about problems with weight? The therapeutic implications of a discourse analytic study. Counsell Psychother Res 3: 25-32.

- McFarlane G, Rennie J (2006) Appendix 2: The Bloke’s Weight – Men’s Weight Management Group Arbroath, March-May 2006. Angus Weight Management Project, Arbroath, Scotland.

- de Souza P, Ciclitira KE (2005) Men and dieting: a qualitative analysis. J Health Psychol 10: 793-804.

- Rolls BJ, Fedoroff IC, Guthrie JF (1991) Gender differences in eating behavior and body weight regulation. Health Psychol 10: 133-142.

- Williams RL, Wood LG, Collins CE, Callister R (2015) Effectiveness of weight loss interventions--is there a difference between men and women: a systematic review. Obes Rev 16: 171-186

APPENDIX 1

Participants Name:

Date of birth:

Ethnicity:

Occupation/employment status:

The Lighten Up programme

How did you come to attend Lighten Up? (GP / practice nurse / health trainer / self-referral)

What prompted you to decide to try to lose weight at that particular point in time? (Personal intentions/goals; GP encouragement)

Can you tell me which commercial weight management programme you chose to attend as part of Lighten Up?

Why did you choose [Weight Watchers / Slimming World / Rosemary Conley]? (location, reputation, previous attendance, timing)

What was your experience of the programme? (if not offered, probe for feeling different/accepted if male or from a minority group)

Best and worst elements of the programme

What messages did you learn that have been most useful?

Did you carry on after the end of the free sessions?

In the past, what other attempts have you made, if any, to lose weight?

• Describe each method and what it involved

• Was it done in isolation or as part of a group (how was this decision reached?)

• It what ways was it successful or unsuccessful (weight-loss).

How long did you attend / keep it up for?

Did you manage to maintain the weight you lost?

Going back to Lighten Up, at the end of the programme did you feel you had the tools to keep up the weight loss?

What were your feelings about being offered help with weight maintenance from the Lighten Up facilitator (by phone at the end of the 12 week slimming group programme)?

You received a ‘Hints and Tips leaflet in the post - did you read it?

If no, was there any particular reason why not? (too wordy, looked like it was repeating things already knew)

If yes, did you learn anything useful from it?

Did you follow any of the weight maintenance strategies it suggested?

How did you get on with these?

Text-based support (not to be asked to usual care patients)

You are currently receiving (or offered the opportunity to receive) weekly texts to help manage your weight. What are your views about the text-based support you are receiving (offered)?

• In what ways was it useful/not useful

• Was the frequency sufficient

• Were the messages appropriate to your needs- if you could re-write the messages what would the messages say

• What are the issues associated with not sending weight scores by text- were there issues with the suitability of the system/personal issues with declaring weight scores

• What other types of information would you like to receive in text messages

Have you, at any time, accessed telephone support?

• If yes, what features were helpful; advice, just knowing that initial support was available

• Would you like to receive emotional support, peer support, counselling over the phone

Behaviour change: The role of society and culture

Can you tell me about someone you know (famous or otherwise) who you consider to be healthy and why you think they are healthy?

• Perceptions of body size

• What routine is followed to achieve this- diet, exercise

• What are the social/cultural interpretations, e.g. Black Caribbean, generally, prefer larger size

Tell me about your current diet?

• Only eating specific foods- cultural/religious requirements; eat at specific times- late in the evening, South Asian/Caribbean/African vs Western foods- which is healthier; does the family all eat the same food together; who cooks the food- female/males; who taught you to cook; alcohol consumption- male identity- particular foods/ practices for differing ethno-religious groups

Do you currently do any regular exercise?

• is it indoor/outdoor- how does the person’s weight influence the type of exercise undertaken; financial constraints, what is the area like in which the person lives in- are there recreational activities/facilities available

• what are the barriers to your exercising or doing more physical activity?

What other strategies are you using to manage your weight?

• Regular weighing, eating regularly, eating more slowly, avoiding distractions when eating (not in front of TV)

In your opinion, why is it important to maintain a healthy weight?

• Clinical risk

• Social attitudes towards people who are over-weight/obese- i.e., stigmatization e.g., fat, lazy

• Others adopting similar behaviours such as children

What aspects of your lifestyle or diet do you find difficult to change (if any) with regards to managing your weight? Why? (Barriers to change- beliefs)

How is your behaviour different/similar to other people?

• Age groups; men/women, ethnic groups, employed/unemployed

Views on services designed for weight-loss

What NHS services are you aware of to manage your weight? (only going to their GP/practice nurse- any other ‘tele-care’ based services)

What support or education would you like to achieve or maintain a healthy weight? (personalised approach; web-based support individual/group; given the opportunity to attend programme; more medical information- GP, lay person)

Citation: Sidhu MS, Aiyegbusi OL, Daley A, Jolly K (2016) Older Men’s Experience of Weight Loss and Weight Loss Maintenance Interventions: Qualitative Findings from the Lighten Up Plus Trial. J Obes Weight Loss 1: 003.

Copyright: © 2016 Manbinder S Sidhu, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.