Surgical Periodontal Treatment: A Case Report

*Corresponding Author(s):

Maurizio SerafiniVia Caduti Sul Lavoro, 37 – 66100 CHIETI, Italy

Email:serafinidrmaurizio@gmail.com

Abstract

Periodontal disease affects patient's health worsening people's quality of life. This clinical case reports the treatment of a 45 years old patient with periodontitis including open flap debridement in first and fourth quadrant and laser treatment on second quadrant. Periodontal treatment improves patient's quality of life when possible without extracting periodontally compromised teeth. Prevention and treatment are aimed at controlling the bacterial biofilm and other risk factors, arresting progression of periodontal disease and restoring lost tooth support.

Keywords

Bacterial plaque; Calculus; Gingivitis; Laser therapy; Open flap debridement; Oral hygiene; Periodontitis; Periodontal support maintenance therapy; Surgical periodontal therapy

Introduction

Periodontal diseases comprise a wide range of inflammatory conditions that affect the supporting structures of the tooth (gingiva, bone and periodontal ligament), which can result in tooth loss and contribute to systemic inflammation. They are strictly related to life style, they are caused by bacteria and their clinical course is influenced by many topical and systemic factors. Periodontal disease includes gingivitis and periodontitis.

Gingivitis

Gingivitis is an inflammatory condition of the gingival tissue restricted to the soft-tissue area of the gingival epithelium and connective tissue and it is a reversible condition if treated.

In the latest International Workshop for a Classification of Periodontal Disease and Condition in 2017, gingival diseases have been classified as follow [1-7]:

Gingivitis Dental Biofilm induced:

- Associated with dental biofilm alone;

- Mediated by systemic or local risk factors such as diabetes mellitus, leukemia, HIV (Figures 1&2);

- Drug influenced gingival enlargement such as anticonvulsant agent (phenytoin), immunosuppressant agents (cyclosporine A), calcium channel blockers (nifedipine), anticoagulants, oral contraceptive agents and others.

The metabolites of these drugs induce fibroblasts proliferation. The result is an imbalance between synthesis and degradation of extracellular matrix.

Figure 1: Dysmetabolic gingivitis hypertrophic associated with dental biofilm and calculus.

Figure 1: Dysmetabolic gingivitis hypertrophic associated with dental biofilm and calculus.

Figure 2: Dysmetabolic gingivitis hypertrophic associated with dental biofilm and calculus.

Figure 2: Dysmetabolic gingivitis hypertrophic associated with dental biofilm and calculus.

Gingivitis non-dental biofilm induced:

- Genetic/developmental disorders such as hereditary gingival fibromatosis;

- Specific infections;

- Inflammatory and immune conditions with oral manifestation such as lichen planus, pemphigoid, lupus erythematosus (Figures 3-6);

- Reactive processes;

- Neoplasms;

- Endocrine, nutritional, and metabolic disease during pregnancy, menstruation and puberty or due to a deficiency of vitamin C;

- Traumatic Lesions accidental or iatrogenic;

- Gingival pigmentation.

Smoke weakens immune system by decreasing gingival blood flow and epithelial changes.

Figures 3-6: Desquamative gingivitis.

Figures 3-6: Desquamative gingivitis.

The main cause is bacterial plaque accumulation around gingival sulcus.

Bacterial plaque is a complex community of bacteria that forms on any surface that is exposed to fluids in the mouth; communication of bacteria within the biofilm allows for production of byproducts; dense, non-calcified, highly organized; firmly adherent to the teeth or other hard materials within the mouth; cannot be washed off by salivary or water flow.

The bacteria more associated with the etiology of gingivitis include species of Streptococcus (mutans, salivarius, mitis, oralis, sanguinis, gordonii,etc), Fusobacterium, Actinomyces, Veillonella, Treponema and others [8].

Pathophysiologically, periodontal disease undergoes four different stages that were first described by Page and Schroeder in 1976 [2]. Gingivitis has been divided into initial, early and established stages, while periodontitis is the advanced stage.

- Initial lesion: characterized by exudative inflammatory response, raised gingival fluid flow, migration of neutrophils from the blood vessel of the connective tissue to the gingival sulcus. This stage occurs within four days of plaque accumulation. There is a destruction of collagen caused by collagenase and other enzymes secreted by neutrophils. Inflammatory infiltrate of the connective tissue is about 5% to 10% [3].

- Early lesion: usually after one week from plaque deposition clinical signs as redness and bleeding appear. The predominant inflammatory cells in this stage are lymphocytes (75%) and macrophages. Inflammatory infiltration ranges from 5% to 15% and loss of collagens reaches 60-70%.

- Established lesion: predominant cells are plasma cells and B-lymphocytes. Collagenolytic activity increases. This stage can remain stable for months, years, or progress to a more destructive lesion.

- Many local factors can increase plaque accumulation such as crowding, malocclusion, dental prosthesis, tooth eruption, due to which plaque removal and oral hygiene can become difficult.

Gum normal clinical features

- Color pale or coral pink

- Texture “orange peel” surface

- consistency firm and resilient to displacement (Figure 7)

Figure 7: Healthy gum.

Figure 7: Healthy gum.

Gingivitis clinical features

- Gingival color from shiny red to bluish

- Gingival contour presents swelling and enlargement

- Possible presence of exudate

- Increased sulcular temperature

- Bleeding upon gentle probing or when brushing or flossing

Calculus

Calcified or mineralized microbial plaque; hard, tenacious mass that forms on tooth surfaces and on dental prosthesis.

Consists of 70-90% inorganic salts including amorphous calcium phosphate, dicalcium phosphate dihydrate, octacalcium phosphate, whitlockite and hydroxyapatite. The organic part consists of proteins, carbohydrates and a minor lipid fraction.

The rough and hardened surface provides an ideal surface for further plaque formation so it plays a main role in periodontal disease. If not removed, supragingival calculus extends to subgingival calculus along the root surface, acting as an irritant to the periodontal tissues, distending the periodontal pocket wall and inhibits the ingress of polymorphonuclear leukocytes [9].

Its formation is facilitated if there are conditions that obstacle an efficient oral hygiene such as crowded teeth, not fitted dental prosthesis, etc.

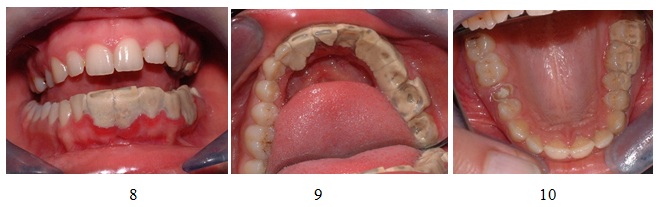

Initially it appears yellowish and easy to remove, by time it absorbs pigments from food, tobacco, drinks, blood and becomes darker and more adherent to tooth surface (Figures 8-12).

Figures 8-10: Calculus clinical appearance.

Figures 8-10: Calculus clinical appearance.

Figures 11,12: Clinical appearance after calculus removal.

Figures 11,12: Clinical appearance after calculus removal.

Treatment

Includes combination of meticulous self-care by individuals, elimination of negative behaviors such as smoking, control of systemic diseases and periodic periodontal maintenance of natural dentition.

The first goal of treating gingivitis is to reduce inflammation by removing dental plaque deposits and calculus including scaling and root planning. According to the severity of the condition, topical and/or systemic antimicrobial agents and antibiotics can be prescribed.

Periodontitis

Periodontitis is a chronic multifactorial inflammatory disease associated with dysbiotic plaque biofilms and characterized by the progressive destruction of the tooth supporting apparatus [4]. Three are the main findings in periodontitis:

- Loss of periodontal tissue support, manifested through clinical attachment loss and radiographically assessed alveolar bone loss

- Presence of periodontal pocketing

- Gingival bleeding.

The new classification from the 2017 World Workshop on Periodontal and Perimplant Disease and Condition identifies three forms of periodontitis [1-7]:

- Periodontitis

- Necrotising periodontitis

- Periodontitis as a direct manifestation of systemic diseases.

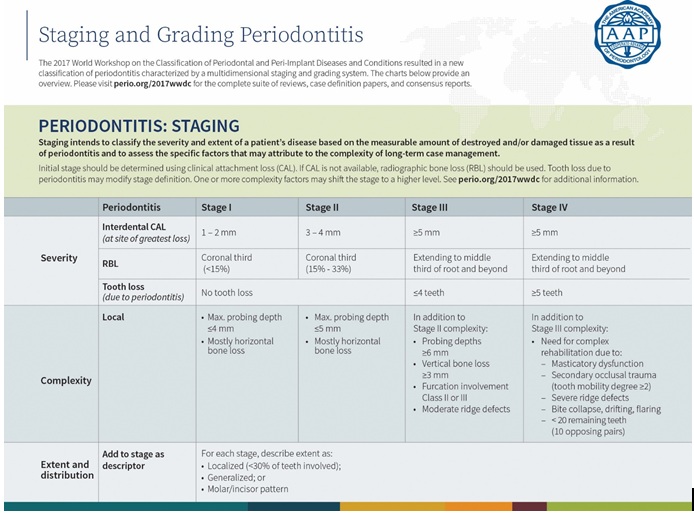

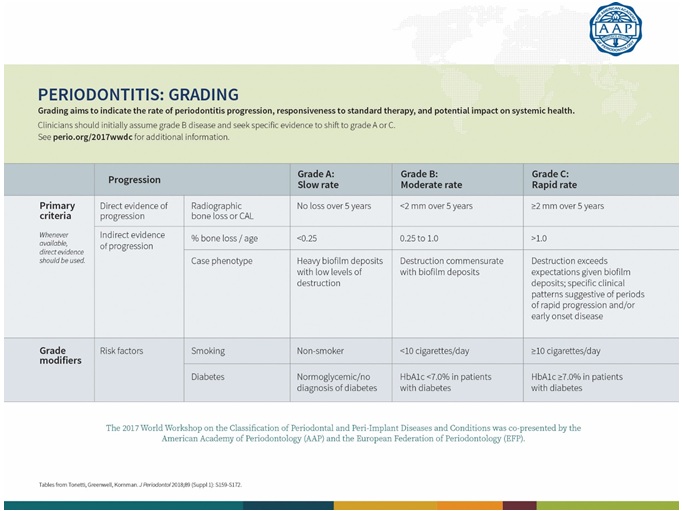

A multidimensional system of stages and grades has been devised to further describe the different manifestation of periodontitis in individual cases. Stages describe the severity and the extent of the disease; grades describe the likely rate of progression (Tables 1&2).

Table 1: Periodontitis Staging.

Table 1: Periodontitis Staging.

Table 2: Periodontitis Grading.

Table 2: Periodontitis Grading.

Pathophysiologically, periodontitis is defined by Page and Shroeder as the advanced stage [2], characterized by attachment loss that is irreversible. The inflammatory changes and the bacterial infection starts affecting the supporting tissues of the teeth and the surrounding structures resulting in their destruction and may eventually result in tooth loss. Plasma cells predominate and junctional epithelium converts in pocket epithelium with a denser inflammatory infiltrate. Subgingival biofilm includes Porphyromonas gingivalis, Aggregatibacter actinomycetecomitans, Tannarella forsythia, Treponema denticola and others Gram – bacteria that cause chronic inflammatory immune response [5]. The evolution of this inflammatory response culminates in the destruction of periodontal tissues.

Treatment

- Patient education, training in oral hygiene and counseling on control of risk factors

- Removal of supragingival and subgingival bacterial plaque and calculus by periodontal scaling and root planning

- Chemotherapeutic agents through local or systemic delivery

- Resective procedures to facilitate effective oral hygiene

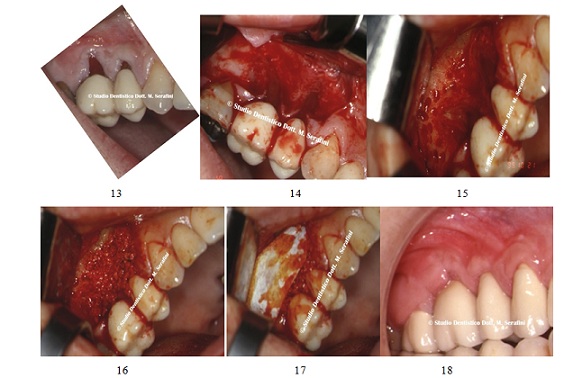

- Periodontal regenerative procedures (Figures 13-18)

- Periodontal plastic surgery

- Occlusal therapy

- Preprosthetic periodontal procedures

- Selective extraction of hopless teeth

- Periodontal laser therapy

Figures 13-18: Bone regeneration surgery.

Figures 13-18: Bone regeneration surgery.

Case Report

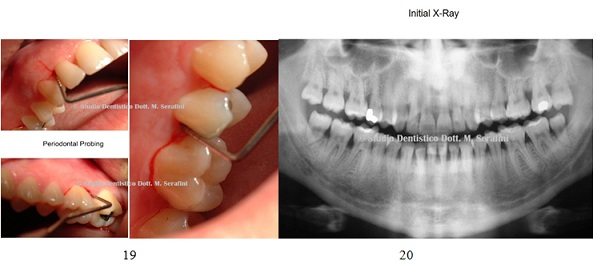

45 years old female patient in good general health and good clinical records presents complaining severe gingival bleeding, halitosis, diffuse pain and sensitive teeth.

The initial examination revealed gingival bleeding and deep probing pocket depth.

X-ray showed horizontal bone defect (Figures 19&20). Figures 19, 20: Periodontal Probing and initial X-ray.

Figures 19, 20: Periodontal Probing and initial X-ray.

The treatment chosen for first and fourth quadrants is an open flap debridement and for the second quadrant a laser irradiation.

Antibiotics was prescribed (amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 1 g two times a day for one week) and 2% chlorexidine solution twice daily.

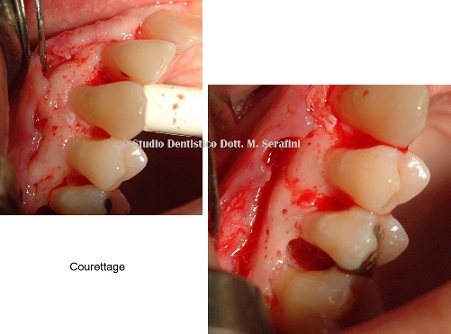

After one week a full thickness flap was raised (Figure 21) on first quadrant region and the granulation tissue and subgingival calculus were removed using curette Gracey and ultrasonic scaler to achieve the smoother root (Figure 22).

Figure 21: Flap raised.

Figure 21: Flap raised.

Figure 22: Courettage.

Figure 22: Courettage.

Animal bone graft mixed with rifampicin was then applied on the defects and the flap sutured. X-ray control was taken after surgery (Figures 23-25).

Figures 23-25: Bone graft, sutures and X-ray postoperative.

Figures 23-25: Bone graft, sutures and X-ray postoperative.

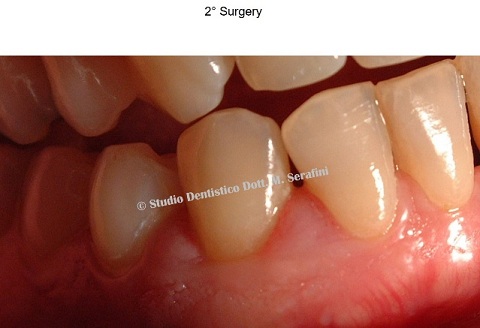

The patient was recalled after 15 days to remove sutures and the clinical examination revealed good healing of soft tissue (Figure 26).

Figure 26: 15 days control.

Figure 26: 15 days control.

After two months, the fourth quadrant was treated after antibiotic therapy (amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 1 g for one week) (Figure 27). Figure 27: Clinical examination.

Figure 27: Clinical examination.

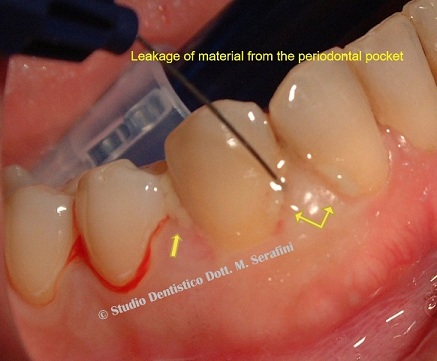

While infiltrating anesthetic, exudate extruded from periodontal pockets as shown in figure 28.

Figure 28: Exudate extruding from periodontal pocket.

Figure 28: Exudate extruding from periodontal pocket.

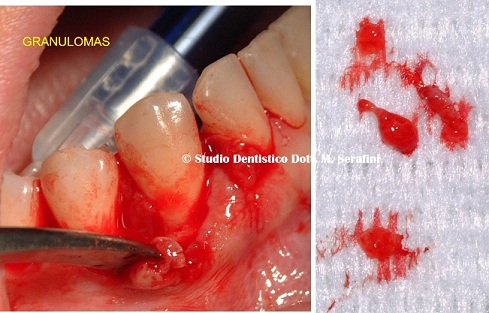

A full thickness flap was raised to perform scaling and root planning and remove all granulating tissue (Figure 29).

Figure 29: Open flap debridement.

Figure 29: Open flap debridement.

Animal bone graft mixed with calcium sulfate was placed on periodontal defects and sutured. Xray was taken after surgery (Figures 30&31).

Figures 30,31: Bone graft and X-ray postoperative

Figures 30,31: Bone graft and X-ray postoperative

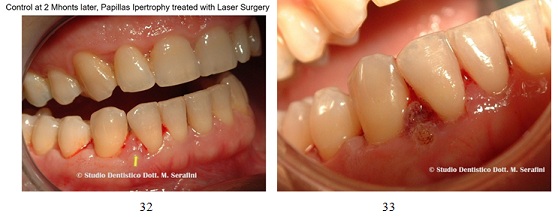

After two months an hyperthrofic interdental papilla between tooth 43 and 44 was treated with a 940 nm diode laser (Figures 32&33).

Figures 32,33: Diode laser treatment.

Figures 32,33: Diode laser treatment.

The second quadrant was treated with 940 nm diode laser with great reduction in gingival inflammation and less invasive postoperative recover for the patient (Figures 34-36).

Figures 34-36: Diode Laser treatment.

Figures 34-36: Diode Laser treatment.

Discussion

The aim of periodontal therapy is to preserve natural teeth, to maintain and improve periodontal health, comfort, esthetics and function. Surgical therapy gives better access for removal of etiological factors reduces probing depth and the goal is to regenerate periodontal tissue lost due to periodontitis. A study by Heitz-Mayfield et al., [6] suggested that chronic periodontitis with pocket depth more than 5 mm, open flap debridement gain clinical attachment level significantly than scaling and root planning only. Judgments regarding treatments must be made by the clinician in light of all the circumstances presented by the individual patient, always based on the latest guidelines. Patient, on the other hand, has to fully understand and be acknowledged that even the best successful periodontal treatment will recur if there is not a periodontal maintenance therapy.

Conclusion

Success on treating this patient responds to several key elements: first of all patient’s education and active participation in his treatment. Surgeon's ability is also fundamental for a successful outcome. Diode laser can be safely and effectively used as an adjunct to the treatment with decreasing of gingival inflammation.

References

- Caton JG, Armitage G, Tonetti MS, Chapple ILC, Jepsen S, et al. (2018) A new classification scheme for periodontal and peri-implant diseases and conditions- introduction and key changes from the 1999 classification. J periodontol89:1-8.

- Page RC, Schroeder HE (1976) Pathogenesis of inflammatory periodontal disease. A summary of current work. Lab Invest34:235-249.

- Page RC (1986) Gingivitis. J Clin Periodontol13:345-359.

- Tonetti MS, Greenwell H, Kornmann KS (2018) Staging and grading of periodontitis: Framework and proposal of a new classification and case definition. Journal of Periodontol89: 159-172. DOI:10.1002/JPER.18-0006.

- Mira A, Simon-Soro A, Curtis MA (2017)Role of microbial communities in the pathogenesis of periodontal diseases and caries. Journal of Clinical Periodontol44:23-38.

- Mayfield H, Trombelli L, Heitz F, Needleman I, Moles D (2002) A systematic review of the effect of surgical debridement vs non-surgical debridement for the treatment of chronic periodontitis.J Clin Periodontol29: 92-102.

- Papanou PN, Sanz M, Buduneli N, Dietrich T, Feres M, et al. (2018) Periodontitis: Consensus report of workgroup 2 of the Periodontal and Peri-implant Diseases and Conditions. J Clin Periodontol45: 162-170.

- Oringer RJ (2002) American Accademy of Periodontology Research, Science, and Therapy Committee: Modulation of the host response in periodontal therapy. J of Periodontol73:460-470.

- Aghanashini S, Puvvalla B, Mundinamane DB, Apoorva SM, Bhat D, et al. (2016) A comprehensive Review on Dental Calculus. J Health Sci Res 7:42-50.

Citation: Serafini M, Teodoro SD, Romondio L, Zagaria L (2022) Surgical Periodontal Treatment: A Case Report. J Stem Cell Res Dev Ther 8: 090.

Copyright: © 2022 Maurizio Serafini, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.