Smarter Interviewing: A Practical Look at Assessing Reliability and Truthfulness in Civil Litigation

*Corresponding Author(s):

Hugh KochChartered Psychologist, Cheltenham And Gloucester Nuffield Hospital, School Of Law, Stockholm University, Cheltenham, United Kingdom

Tel:+01242 263715,

Fax:+01242 528299

Email:hugh@hughkochassociates.co.uk

Abstract

Issues of assessing reliability and truthfulness are discussed in the context of forensic, judicial and clinical settings in relation to civil compensation cases. Theoretical and practical issues are described. The overall importance of congruent communications is stressed.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

In all social and professional contexts, humans communicate verbally and non-verbally in ways which at times are either unreliable or untruthful or both. In forensic and judicial settings, experts assessing claimant or offender behaviour attempt to categorise information given in terms of its reliability, validity and truthfulness [1]. Motivation to provide unreliable information can vary from social acceptability, reduction of actual or possible conflict, malicious or financial gain, or avoidance of punishment [2,3].

This article presents current thinking in the field of deception detection as applied to an anonymised case study relating to a recent civil compensation claim.

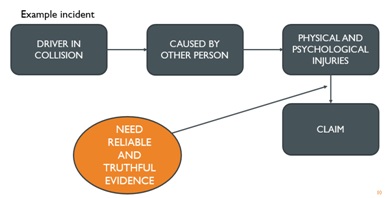

When compiling evidence in a civil claim for personal injury such as a Road Traffic Collision (RTC) (Figure 1), it is crucial that the expert witness is mindful of how reliable or truthful the evidence available is;

Figure 1: Reliable evidence in civil litigation.

Figure 1: Reliable evidence in civil litigation.

From a legal perspective, evidential reliability is based on the quality and extent of the available data (e.g., self-report, medical records), the inferences made, the precision of tests or questionnaires used, and the range of opinion. However, the most crucial data is that of the claimant’s self-report, obtained from the interview. This informs the key medico-legal answers of diagnosis, causation, duration and prognosis. For the expert’s opinion to be robust, fair and just, he/she must be aware of how reliable the self-report information is. These issues are discussed below in relation to an anonymised case study.

CASE STUDY

Mr Jones (31) lives in Exeter and works in the local council offices. He drives 10 miles each way to get to and from work.

He described having a significant RTC on the M5 where it meets the A38 Devon road. He stated that he was hit from behind and pushed into the central reservation, hitting another car. He has reported that he has developed traumatic stress, a fear of driving and subsequently had to have 6 months off work and is still off, due to both physical and psychological difficulties following the RTC.

ANONYMISED INTERVIEW

Mr Jones walks into the clinic room, holding his back and making grunting noises - he walks slightly stooped.

Q1: Where do you have pain?

A1: Er, umm, all over - all the time

Q2: How was your journey today?

A2: Traumatic - the train was packed, I couldn’t get a seat all the way. Then your directions sent me the wrong way.

Q3: Sorry about that. Have you got the questionnaire we sent you, please?

A3: Yes, but I haven’t completed it - I’m fed up of forms and anyway, most of it didn’t seem relevant.

Q4: Have you got any ID, please?

A4: No, why do you need that?

Q5: We have to ask all our clients for this. So, we’re here to talk about the Road Traffic Collision (RTC) in August, last year. I need to ask you several questions. Have you ever had a significant RTC before?

A5: (Pause for 5 seconds). No - I’m a good, careful driver.

Q6: Have you ever been to your GP, before the accident about any emotional problems, such as depression or anxiety?

A6: Uhrr-mm, no, not really.

Q7: Have you ever had any psychological or psychiatric care before the accident?

A7: (Look away before answering, then answer without looking at X.) (3 second pause). No, I don’t think so…

Q8: Excuse me asking, but have you ever had any problems with the police?

A8: (Shifting in chair, move legs) Why do you want to know?

Q9: I ask everyone background questions, and this is one of them, it’s important as it helps with our overall assessment.

A9: No, not really - nothing serious. (Blinking 3 times in rapid succession).

Q10: That sounds as if you have had some difficulties - can you explain a little more please?

A10: Well, five years ago, I got done for no insurance on my car. That’s not relevant to this, is it?

Q11: If I had met you just before this accident, how were you feeling?

A11: (Scratching his head a lot; pausing) just after the accident?

Q12: No just before.

A12: I was ok. (Pause). I had been a bit down at work and my GP had given me some sleeping tablets - I think it was then, or it might have been the year before - I can’t remember.

Q13: Ok, so tell me briefly about this accident - you were driving? Where was this? Did you have your seat belt on?

A13: Yes, I did - it was on the M5 where it meets the Exeter road, I think - somewhere around there. No, I know, it was just where the A38 starts at Topsham.

Q14: I understand you were hit from behind, then you hit a barrier and into another car? Is that correct?

A14: Something like that. All hell let loose - the other drivers’ alarm went off and he was blocking the fast lane. The other guy walked with a limp - his car was full of shopping.

Q15: Roughly what time was it?

A15: Don’t know. In the afternoon sometime.

Q16: What was the weather like?

A16: I remember it was grey, overcast and had been raining - because I’d had my wipers on front and back for about 15 minutes. It was particularly bad on this stretch of road.

Q17: Did you lose consciousness when you were hit?

A17: I think so, it was a real shock - I tried to avoid the barrier and the other cars and I was really relieved to come to a halt. I was worried I had been hurt but also worried because the other driver looked very shaken up.

Q18: When it was happening did you think you were going to die?

A18: Oh yes, after I got out, a policeman said I was lucky to get out alive. I think I had PTSD (no emotion shown here or when answering questions about details of the RTC).

Q19: Did you go to hospital straight away?

A19: No, the next day, or maybe two days later - RD&E hospital in Exeter.

Q20: Did you see your GP? Did anyone support you go?

A20: Sorry, I’m not sure. Yes about one week later I think - not sure. Yes, my sister supported this would be a good idea.

Q21: Did you discuss any emotional problems with your GP? Did he suggest any treatment?

A21: Oh yes, we talked about it - I got given some tablets. I wasn’t there long, he’s always very busy. I do remember him saying he had a road accident on the same stretch of road. My sister, who is a psychologist, recommended I should have therapy or counselling.

Q22: Over the next month, did you have problems sleeping?

A22: Yes, I had nightmares every night, always about this awful accident and being in my red car. I also had flashbacks a lot, remembering what happened. My wife thought I had PTSD. I still have nightmares every night.

Q23: Let’s talk about the effect this had on your driving - was the car written off?

A23: Yes, I couldn’t replace it because I was so scared - I didn’t drive for ages afterwards.

Q24: How long did you have off work?

A24: About four weeks. I remember this because my wife pointed out I returned to work on my son’s birthday.

Q25: What did you do during that time?

A25: Oh, nothing really.

Q26: I notice that the medical report by Dr Bloggs says you said you were off work for two weeks?

A26: I was, but when I went back, after two hours I couldn’t cope and had another two weeks off.

Q27: Did they give you a courtesy car?

A27: Oh yes, it was a big car though - I didn’t drive it much. I remember saying to the garage guy that the car was much bigger than mine. He said it was the only one available.

Q28: When you went back to work, how did you get there?

A28: A friend picked me up for the first two weeks. I was very anxious and kept pointing this out to him which made him angry. I then got my insurance money and bought another car and drove to work.

Q29: How did driving feel?

A29: Awful, I was very frightened - the road is full of idiots and I’m always afraid of being hit again.

Q30: How is driving now, six months on?

A30: A little better, but I notice on that stretch of motorway, people drive very closely to each other - especially near the ‘services’ exit.

Q31: Have there been any changes on this stretch of road?

A31: Yes, I think so

Q32: Reading your GP notes I see you had several prescriptions for antidepressants and sedatives in 2010, 2012, 2013 and 2015?

A32: I’d forgotten about that.

Q33: Post-accident, you attended A&E one week later, attended GP three weeks later and there is no reference to RTC in your GP notes and no extra medication prescribed, just previous sedatives.

A33: It’s difficult to remember clearly.

Verbal and non-verbal behaviour in the context of deception detection has been well researched [4]. Below are examples of these deception-related behaviours which were apparent in the case study (Table 1).When assessing veracity, the interviewer looks for positive characteristics which endorse reliability. Examples of these from the case study are in table 2.

|

Interview Answer No |

|

|

Vocal Characteristics |

|

|

1. Speech hesitations: use of words ‘ah’, ‘um’, ‘er’ and so on |

A1 |

|

2. Speech errors: word and/or sentence repetition, sentence change, sentence incompletions, slips of the tongue, and so on |

A19 |

|

3. Latency period: period of silence between question and answer |

A7 |

|

Facial Characteristics |

|

|

4. Gaze: avoiding the face of the conversation partner |

A7 |

|

5. Blinking: Blinking of the eyes |

A9 |

|

Movements |

|

|

A11 |

|

Shifting position: movements made to change the sitting position (usually accompanied by trunk and foot/leg movements) |

A8 |

Table 1: Examples of Non-verbal behaviour during the interview indications of possible unreliability.

|

|

Interview Answer No |

|

General Characteristics |

|

|

1. Logical structure |

A16 |

|

2. Unstructured production |

A16 |

|

3. Quantity of details |

A16 |

|

Specific Contents |

|

|

4. Contextual embedding |

A24 |

|

5. Descriptions of interactions |

A26 |

|

6. Reproduction of conversation |

A26 |

|

7. Unexpected complications during the incident |

A14 |

|

8. Unusual details |

A14 |

|

9. Superfluous details |

A14 |

|

10. Accounts of subjective mental state |

A17 |

|

Motivation-related Contents |

|

|

11. Spontaneous corrections |

A13 |

|

12. Admitting lack of memory |

A20 |

|

13. Raising doubts about one’s own testimony |

A15 |

Table 2: Some examples of possible reliable content.

In addition to actual verbal and non-verbal characteristics of unreliability in the interview, the interviewer also listens out for general psychological characteristics, motivational factors and inconsistencies. Examples of these from the case study are in table 3.

|

Interview Answer No |

|

|

Psychological Characteristics |

|

|

1. Inappropriateness of language and knowledge |

A18 |

|

2. Inappropriateness of affect |

A18 |

|

3. Susceptibility to suggestion Motivation |

A30 |

|

Motivation |

|

|

4. Questionable motives to report |

A20 |

|

5. Questionable context of the original disclosure or report |

A21 |

|

6. Pressures to report falsely (e.g., avoid detection; obtain compensation) |

A22 |

|

Investigative Questions |

|

|

7. Inconsistency with the laws of nature |

A22 |

|

8. Inconsistency with other statements |

A26 |

|

9. Inconsistency with other evidence |

A33 |

Table 3: Examples of possible interview validity issues.

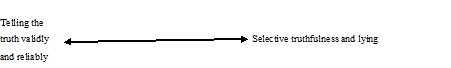

Truthfulness Continuum: Truthfulness like most other behaviours is a continuum as shown below:

On this continuum claimants commonly display the following characteristics:-

• Omission of key information

• Exaggeration of information

• Inconsistency of approach between two or more areas

• Suggestibility for producing erroneous accounts under interviewing

The search for evidential certainty relies on incremental observation and consideration throughout the litigation ‘trail’, the search for ‘best fit’ opinion, increasing objectivity and the expert’s impartiality and independence.

THREE CONTINUA OF UNRELIABILITY

Unreliability

Self-report without reliability: The patient, through guardedness, exaggeration, or denial of symptoms, convinces the clinician that his or her responses are inaccurate. Such cases may be suspected of malingering or defensiveness, although the patient’s intent cannot be unequivocally established.

Defensiveness

• Mild defensiveness: There is unequivocal evidence that the patient is attempting to minimize the severity but not the presence of his or her psychological problems. These distortions are minimal in degree and of secondary importance in establishing a differential diagnosis.

• Moderate defensiveness: The patient minimizes or denies substantial psychological impairment. This defensiveness may be limited to either a few critical symptoms (e.g., paedophilic interest) or represent lesser distortions across an array of symptomatology.

• Severe defensiveness: The patient denies the existence of any psychological problems or symptoms. This categorical denial includes common foibles and minor emotional difficulties that most healthy individuals have experienced and would acknowledge.

Malingering

• Mild malingering: There is unequivocal evidence that the patient is attempting to malinger, primarily through exaggeration. The degree of distortion is minimal and plays only a minor role in differential diagnosis.

• Moderate malingering: The patient, either through exaggeration or fabrication, attempts to present him- or herself as considerably more disturbed than this is the case. These distortions may be limited to either a few critical symptoms (e.g., the fabrication of hallucinations) or represent an array of lesser distortions.

• Severe, malingering: The patient is extreme in his or her fabrication of symptoms to the point that the presentation is fantastic or preposterous

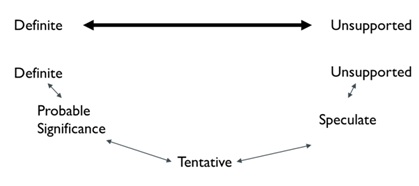

Evidential certainty of deception is rarely black and white [5], but falls somewhere on the overall dimension in figure 2 below:

Figure 2: Evidential certainty of deception.

Figure 2: Evidential certainty of deception.A description of the anchor points illustrated above are shown in table 4 opposite.

|

Definite |

Unsupported |

|

Unsupported |

Non-significant or conflicting research findings. |

|

Speculative |

Conclusions that are consistent with accepted theory and supported by one or two studies of limited generalizability. |

|

Tentative |

Research studies consistently show statistical significance in the expected direction, but have little or no practical value in classifying individuals. |

|

Probable Significances |

Research studies consistently establish statistical significance in which cutting score, measures of central tendency, or a similar statistic accurately differentiate between at least 75% of the criterion groups. |

|

Definite |

Accurate classification of 90% or more of individual person based on extensive, cross-validated research. Findings are congruent with accepted theory. |

Table 4: Outsmarting the unreliable historian: Cognitive lie detection approach.

The key to deception detection is the ability to listen and ‘watch’ interviewee’s verbal and non-verbal behaviour very carefully. However, in addition to this, researchers [6] have developed a strategy for increasing cognitive load with the aim of eliciting a higher rate of deception cues from untruthful claimants. It is suggested that to do this requires:

• Asking questions to raise cognitive load in liars

• Making interview more difficult (reverse order story telling; keep eye contact and tell story; ask unanticipated questions; ask devil-advocate questions; strategic use of evidence (which client is avoiding e.g., use of car hire)

This results in more non-verbal deceit cues and greater potential for detection.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PROFESSIONAL PRACTICE

Much debate centres on how successful expert interviews can detect deceptive behaviour [7]. It is suggested that greater emphasis be placed by experts on actual interviewee behaviour, including verbal and non-verbal behaviour, and how the expert develops an incremental picture of the interviewee’s veracity and to what extent there is a range of opinion when faced with this array of data.

To catch the unreliable historian out, the expert needs:

• A questioning, challenging attitude

• A probing, repetitious, questioning attitude where necessary

• A withholding attitude at times (i.e., non-disclosure of what is already known)

• Well researched, background information prior to interview

• Integrate an array of clinical findings on the issue of dissimulation.

• Strength and consistency of results across various measures

• Absence of alternative explanations

This should be a subject taught at undergraduate and postgraduate levels of both psychology and law courses and also a key topic considered as part of CPD for qualified and experienced lawyers and experts in the field.

REFERENCES

- Drogin EY (2015) Special Issue on New Challenges in Psychology and Law. Int J Law & Psychiatry 42-43: 1-188.

- Koch HCH, Newns K, Boyd T, Peters J (2016) Assessing Malingering and Deception in Forensic, Judicial and Clinical Contexts: Are Various Communications “Congruent”? Expert Witness Journal.

- Koch HCH (2016) Legal Mind: Contemporary Issues in Psychological Injury and Law. Expert Witness Publications, Manchester, UK.

- Vriz A (2000) Detecting lies and deceit: the psychology of lying and the implications for professional practice. John Wiley, New Jersey, USA. Pg.no: 254.

- Milchman (2015) Weighing evidence in psychological experts opinion. Paper presented to IALMH conference, Vienna.

- Aldert Vrij A, Granhag PA, Mann S, Leal S (2010) Outsmarting the Liars: Toward a Cognitive Lie Detection Approach. Association for Psychological Science 1-5.

- Oxburgh G, Myklebust T, Grant T, Milne R (2016) Communication in Investigative and Legal Contexts: Integrated Approaches from Forensic Psychology, Linguistics and Law Enforcement. John Wiley & Sons, New Jersey, USA.

Citation: Koch H, Beesley F (2017) Smarter Interviewing: A Practical Look at Assessing Reliability and Truthfulness in Civil Litigation. J Forensic Leg Investig Sci 3: 016.

Copyright: © 2017 Hugh Koch, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.