Community Gardening, Volunteerism and Personal Happiness: “Digging In” to Green Space Environments for Improved Health

*Corresponding Author(s):

August John HoffmanDepartment Of Psychology, Metropolitan State University, Minnesota, United States

Tel:+1 6519995814,

Email:August.Hoffman@metrostate.edu

Abstract

“HAPPINESS IS NOT A GOAL... BUT A BY-PRODUCT OF A LIFE WELL LIVED”- ELEANOR ROOSEVELT

Paradoxically, reports of personal happiness and compassion are highest when we focus less on the needs of ourselves and respond more to the needs of other individuals within our community, or what Diener and Ng [2] refer to as “social psychological prosperity”. Recent research has addressed some consistent characteristics among people who rank in the highest percentiles among tests measuring happiness, including stronger tendencies towards extroversion, agreeableness and subjective (i.e., positive) states of well-being [3]. More recently, however, an important universal component (i.e., social capital) has been associated with reports of personal happiness and subjective states of well-being. Social capital has been described as a capacity of developing networks within communities that involves key components in the creation and maintenance of human relationships, including trust, communication, reciprocity and cooperation .

BUILDING SOCIAL CAPITAL THROUGH COMMUNITY GARDENS

Community gardening programs and neighborhoods that provide increased access to green space activities are unique in that they help contribute to the development of social capital in providing residents with greater opportunities to communicate directly with each other and to participate in transformative programs that effect positive change and growth, such as increased health and nutrition [5]. More recently, empirical research has identified the viability and importance in maintaining and developing social capital among underserved communities and providing adequate educational resources, such as urban schools [6], mental health resources [7], and even natural disaster recovery efforts (i.e., landslides, hurricanes and floods) [8].

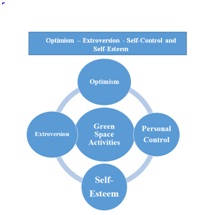

In their recent empirical research addressing how psychologists may better understand the development of positive states of well-being and happiness, David Meyers and Ed Diener [9] explored several factors that have been correlated with happiness, such as faith or religious belief systems, income (i.e., wealth vs. poverty) and gender. More specifically, Meyers and Diener [9] identify four traits that have been associated with personal reports of happiness and improved psychological states of well-being (Figure 1):

• Extroversion: An extroverted personality may include qualities such as feeling comfortable around other people and exchanging or sharing ideas with different groups of individuals.

• Personal control: A strong sense of control of events within one’s life (i.e., internal locus of control) refers to a belief that after initial failure, people can generally change the course of events in their lives if they wish.

• Self-esteem: Self-esteem has been described generally as a sense of how we feel about ourselves and the willingness to take on new challenges in our lives.

In this article we hope to identify how different types of volunteer work and the development of “green space” outdoor activities, such as community gardens, flower or sensory gardens and fruit tree orchards may contribute to increased positive subjective states of well-being and personal happiness. More specifically, we hope to examine how volunteerism involving green space locations such as community gardening programs may help promote both “community connectedness” and social capital and how these qualities may interact, influence and contribute to the development of the four domains of happiness as described by Myer and Diener [9].

THE ADVANTAGES OF SUSTAINABLE GREEN SPACE PROGRAMS AND COMMUNITY GARDENS

While numerous empirical studies have identified green space and natural environments as important contributors to improved physical and mental health (see for example, [10,14,15], currently little data exists addressing how participation in green space and environmental activities may actually foster and contribute to a stronger sense of connectedness to the community within the context of fostering general positive emotions such as compassion and happiness. The current study examines more closely the relationship between participation in green space activities, volunteerism, perceptions of “community connectedness” and improved psychological states of well-being.

Perhaps one of the most important benefits of community gardening is its inherently inclusive and collaborative nature. It is an activity that can be shared and experienced by virtually all groups of people, from different socioeconomic backgrounds, cultures, and ages. Community gardens can also help bring together individuals from different cultural backgrounds in promoting different types of healthy foods and sharing those foods within their community. The assimilative practices of community gardens have also been noted to be highly instrumental with refugee or immigrant populations (i.e., Bhutanese) in their adjustment to their new homeland in the upper Midwest [16]. In this particular study, recent refugee immigrants who had participated in a variety of community gardens in the upper Midwest region (i.e., twin cities area, Minnesota) had fewer reports of depression and increased self-esteem given the opportunities to work with their family members and community residents in the maintenance and development of their garden areas. Several of the respondents in this study also noted that the reason why community gardening had helped them in their adjustment to the United States was “gardening here makes us feel like we are living in our own country” (Pg no. 1157). Another added component to the positive effects of community gardening was the structure and democratic process in which the community gardens are established.

The process of sharing not only the foods grown in the community garden, but the shared responsibility of maintaining the growth process of the vegetables (i.e., weeding and irrigation) and care for the gardening equipment (shovels, spades and hoes) helped foster a greater sense of “social connectedness” among the refugees and community residents of the twin cities area.

EXPOSURE TO GREEN SPACE ENVIRONMENTS, OPTIMISM AND PSYCHOLOGICAL STATES OF WELL-BEING

Natural or green space environments, such as community gardens, forests and fruit tree orchards have been noted by a number of researchers to have strong appeal to the public because of their universal appeal to our senses. In many ways, vegetable and sensory gardens are viewed as sanctuary spaces because of the serenity and solitude that they provide (Figure 2). The vibrant colors produced by plants and the attractive aromas produced by a variety of fragrant flowers draws individuals to the outdoor gardens and provides psychological soothing benefits to those individuals suffering from anxiety and depression [17]. Green space environments have also been identified as therapeutic in that they provide numerous opportunities for individuals who may be suffering from stress and anxiety to engage in more frequent outdoor physical activity and gain more exposure to positive forms of social interaction with peers and local residents [18]. Community gardens provide an ideal forum for individuals to work and interact cohesively in the development and maintenance of what Madeleine Guerlain and Catherine Campbell [19] refer to as “health-enabling social spaces” (Pg no: 222). In this study several volunteers were interviewed who had participated in several community gardens located in East London. The researchers determined that the gardens provided individuals with opportunities to escape stressful environments that were typically associated with urban dwelling and provide opportunities to better “connect” with other residents of their own community. Additionally, the community gardens provided a convenient location for the participants to work collectively with each other and identify various skills that helped build important interpersonal qualities such as social capital, collective self-efficacy and perceptions of positive change to the community.

Figure 2: Inver Hills - Metropolitan State Community Garden, 2018.

Teaching individuals how to grow healthy foods within communities that have been traditionally characterized as “food deserts” can help foster important intrapersonal traits, such as autonomy and self-worth. Additionally, individuals who participate in the development of green sustainable programs that emphasize healthier eating programs can also provide a more positive future among historically underserved groups [19]. Community gardening also provided a sense of economic empowerment in that individuals were providing healthy foods for their families which also contributed to a stronger sense of achievement and self-worth. By participating in the development and maintenance of the community gardening program in London, the participants indicated that no matter how stressful or complex the “outside world” may become, the shared green space environments provided a more natural way to relieve financial stress while interacting and socializing with individuals who shared common interests.

More recent research has also identified that proximity to urban dwellings where traffic and pollution exist in more concentrated amounts can pose as physical health hazards. Additionally, proximity to congested urban dwellings may not only pose physical health hazards but also present mental health problems as well, such as depression and anxiety [20]. Conversely, living near or have access to green space environments has been identified as instrumental in not only reducing mental stress and anxiety [21], but also help improve levels of physical health through reduced obesity and overall BMI levels [22].

COMMUNITY GARDENING PROGRAMS, SOCIAL CAPITAL AND EXTROVERSION

Community gardens serve as central neighborhood locations for individuals to not only produce healthier foods where they may be scarce (commonly referred to as food deserts), but in many neighborhoods they serve as important physical (i.e., real time) locations for people to share critical information with each other, promote trust among residents and ultimately build relationships that enhance social capital within neighborhoods [5]. The community gardens can serve both as bonding agents to help bring historically diametrically opposed groups together through sharing resources in the maintenance of the gardens and also serve as “bridges” to extended communities where individuals may have limited contact with other residents in geographically more distant regions and neighborhoods. Neighborhoods that provide opportunities for residents to communicate and discuss central issues to help improve and beautify their local environments through artwork, flower and vegetable gardens and developing community art spaces were identified as highly instrumental in helping people to build trust with previously unknown neighbors, promote stronger sense of self-efficacy, and generally facilitate a greater sense of community pride [24].

METHODS

Participants

Results

| Correlations | CSW as Important Activities | Volunteering Makes me Feel Better | Contributing to a Better Society | Increased Connectedness To Community | Increased Environmental Awareness | |

| Volunteering Makes me Feel Better as a Person | Sig. (2-tailed) | 0 | 0 | 0.008 | 0.003 | |

| N | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | |

| Volunteering as Contributing to a Better Society | Pearson Correlation | 0.639** | 0.675** | 1 | 0.649** | 0.443* |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.001 | 0 | 0 | 0.027 | ||

| N | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | ||

| Increased Connectedness to Community | Pearson Correlation | 0.431* | 0.519** | 0.649** | 1 | 0.431* |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.031 | 0.008 | 0 | 0.032 | ||

| N | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | |

| Increased Environmental Awareness | Pearson Correlation | 0.522** | 0.566** | 0.443* | 0.431* | 1 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.007 | 0.003 | 0.027 | 0.032 | ||

| N | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | |

Discussion

Figure 3: Vegetables grown in the Inver Hills - Metropolitan State University Community Garden, Circa, 2017.

Figure 3: Vegetables grown in the Inver Hills - Metropolitan State University Community Garden, Circa, 2017.I like doing community service work projects because I feel more connected to the organization I am working with and the community in general. I like meeting new people, particularly different types of people that I wouldn’t normally encounter in my day-to-day life. I also appreciate that community service often involves learning or practicing a new skill, which can engaging and satisfying. I enjoy volunteering in green space environments primarily because if just feels nice to be in nature. I spend the majority of my days on a computer, so it feels freeing and fulfilling to spend time in green spaces, I also enjoy working with my hands for similar reasons; the tangible aspects of physical work can be very satisfying. Lastly, I feel passionately about the environment and I like being able to support green or environmentally-focused projects.

Several of the participants also indicated that they enjoyed working outdoors in the garden and especially appreciated the physical qualities of the environment, such as digging in the earth and working with plants. For those student volunteers who participated in outdoor environmental service work activities, several comments indicated a unique preference to work outdoors and the benefits of working in a serene and natural environment.

It sounds counter-intuitive, but I love the feeling of dirt under my fingernails, and the way grime pours off of me in the shower after I spend the day outside caring for plants that I won’t eat the produce from. There is just something about using your own hands to grow food that others will eat, knowing that a child who might have had potato chips for dinner won’t have to settle for empty calories. Of all the community service I do, I find gardening to be the most enjoyable and the most rewarding. The connection to nature is unbeatable, and the work is so meaningful. Being able to directly influence what goes on a child’s plate is amazing to me, and I hope that everyone gets to experience that feeling at some point in their lives.

Limitations of the Study and Future Recommendations

Conclusion

REFERENCES

- Piff PK, Moskowitz JP (2017) Wealth, poverty, and happiness: Social class is differentially associated with positive emotions. Emotion.

- Diener E, Ng W, Harter J, Arora R (2010) Wealth and happiness across the world: Material prosperity predicts life evaluation whereas psychosocial prosperity predicts positive feeling. J Pers Soc Psychol 99: 52-61.

- Diener E, Seligman MEP, Choi H, Oishi S (2018) Happiest people revisited. Perspectives on Psychological Science 13: 176-184.

- Putnam RD (2001) Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. Simon and Schuster, New York, USA.

- Alaimo K, Reischl TM, Allen JO (2010) Community gardening, neighborhood meetings, and social capital. Journal of Community Psychology 38: 497-514.

- Riley KA (2013) Walking the leadership tightrope: Building community cohesiveness and social capital in schools in highly disadvantaged urban communities. British Educational Research Journal 39: 266-286.

- Boyd CP, Hayes L, Wilson RL, Bearsley-Smith C (2008) Harnessing the social capital of rural communities for youth mental health: An asset-based community development framework. Aust J Rural Health. 16: 189-193.

- Loebach P, Stewart J (2015) Vital linkages: A study of the role of linking social capital in a Philippine disaster recovery and rebuilding effort. Social Justice Research 28: 339-362.

- Myers DG, Diener E (2018) The scientific pursuit of happiness. Perspect Psychol Sci 13: 218-225.

- Beyer MM, Kaltenbach A, Szabo A, Bogar S, Nieto FJ, et al. (2014) Exposure to neighborhood green spaces and mental health: Evidence from the survey of the health of Wisconsin. Int J Environ Res Public Health 11: 3453-3472.

- Roe JJ, Thompson CW, Aspinall PA, Brewer MJ, Duff EI, et al. (2013) Green space and stress: Evidence from cortisol measures in deprived urban communities. Int J Environ Res Public Health 10: 4086-4103.

- Bowler DE, Buyung-Ali LM, Knight TM, Pullin AS (2010) A systematic review of evidence for the added benefits to health of exposure to natural environments. BMC Public Health 10: 456.

- Cox DT, Shanahan DF, Hudson HL, Fuller RA, Anderson K, et al. (2017) Doses of nearby nature simultaneously associated with multiple health benefits. Int J Environ Res Public Health 14: 172.

- Wolfe MK, Groenewegen PP, Riijken M, de Vries S (2014) Green space and changes in self-rated health among people with chronic illness. European Journal of Public Health 24: 640-642.

- Huynh Q, Craig W, Janssen I, Pickett W (2013) Exposure to public natural space as a protective factor of emotional well-being among young people in Canada. BMC Public Health 13: 407.

- Hartwig KA, Mason M (2016) Community gardens for refugee and immigrant communities as a means of health promotion. J Community Health 41: 1153-1159.

- Hartig T, Mang M, Evans GW (1991) Restorative effects of natural environment experiences. Environment and Behavior 23: 3-26.

- Groenewegen PP, van den Berg AE, de Vries S, Verheij RA (2006) Vitamin G: Effects of green space on health, well-being, and social safety. BMC Public Health 6: 149.

- Guerlain MA, Campbell C (2016) From sanctuaries to prefigurative social change: Creating health-enabling spaces in East London community gardens. Journal of Social and Political Psychology 4: 220-237.

- Sundquist K, Frank G, Sundquist J (2004) Urbanisation and incidence of psychosis and depression: Follow-up study of 4.4 million women and men in Sweden. Br J Psychiatry 184: 293-298.

- White MP, Alcock I, Wheeler BW, Depledge MH (2013) Would you be happier living in a greener urban area? A fixed-effects analysis of panel data. Psychol Sci 24: 920-928.

- Dietz WH (2015) The health effects of green space: Then and now. International Journal of Obesity 39: 1329.

- Cheng H, Furnham A (2003) Personality, self-esteem, and demographic predictions of happiness and depression. Personality and Individual Differences 34: 921-942.

- Allen JO, Alaimo K, Elam D, Perry E (2008) Growing vegetables and values: Benefits of neighborhood-based community gardens for youth development and nutrition. Journal of Hunger and Environmental Nutrition 3: 418-439.

- Hoffman AJ (2010) Community service questionnaire. Unpublished manuscript.

- Hoffman AJ (2017) Creating a culture of transformation in Guatemala: One fruit tree at a time. Electronic Green Journal 1.

- Sherif M, Harvey OJ, White BJ, Hood WR, Sherif CW (1961) Intergroup conflict and cooperation: The Robber’s Cave experiment. Oklahoma, USA. Pg no: 1-18.

- Okvat HA, Zautra AJ (2011) Community gardening: A parsimonious path to individual, community and environmental resilience. Am J Community Psychol 47: 374-387.

- Hoffman AJ, Doody S, Veldey S, Downs R (2016) Permaculture, fruit trees and the “Motor City”: Facilitating eco-identity and community development in Detroit, Michigan. National Civic Review 105: 3-7.

- Thompson CW, Roe J, Aspinall P, Mitchell R, Clow A, et al. (2012) More green space is linked to less stress in deprived communities: Evidence from salivary cortisol patterns. Landscape and Urban Planning, 105: 221-229.

APPENDIX

Please answer the following questions where a score of:

1 = Absolutely Untrue

2 = Somewhat Untrue

3 = Undecided

4 = Somewhat True

5 = Absolutely True

1. I feel that participating in volunteer or community work is an important activity that all people should be involved in _____;

2. When I participate in volunteer work and community service work, I feel better as a person _____;

3. When I participate in volunteer and community service work, I feel as though I am contributing to make society better for all people _____;

4. I feel more “connected” to my school and community when I participate in community service work ____;

5. After participating in community service work I feel more like I “belong” to my campus and community _____

6. When I participate in community service work, I feel as though I can accomplish more and learn more academically_____;

7. When I participate in volunteer or community service work, I feel as though I am more capable of accomplishing other types of goals in my life _____;

8. I feel as though my potential for school work and academics has improved significantly while I have been participating in community service activities _____;

9. Since participating in this project, I feel as though I am more likely to participate in future community service activities _____;

10. When I participate in volunteer or community service work, I like working outside in the environment and enjoy how the activity makes my body feel physically _____;

11. I feel that I have a better understanding of members from different ethnic groups since I have been working in my community service activity _____;

12. When working as a volunteer in the community, I feel that my sense of pride for the community and my school has also increased _____;

13. I feel that community service work has helped me to better understand other people and to understand different cultures _____;

14. I feel more comfortable in communicating and working with members from different ethnic groups since my community service activity ______;

15. Since my community service work I feel like I am more aware of my environment _____ .

II) General or overall comments regarding your community service work project-What did you like (or dislike) in particular? Any unique experiences that you would like to share?

Citation: Hoffman AJ (2018) Community Gardening, Volunteerism and Personal Happiness: “Digging In” to Green Space Environments for Improved Health. J Psychiatry Depress Anxiety 4: 015.

Copyright: © 2018 August John Hoffman, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.