Journal of Ophthalmology & Clinical Research Category: Clinical

Type: Case Report

Bilateral Central Retinal Vein Occlusion in a Patient with Mantle Cell Lymphoma

*Corresponding Author(s):

Toshiyuki OshitariDepartment Of Ophthalmology And Visual Sciences, Graduate School Of Medicine, Chiba University, Inohana 1-8-1, Chuo-ku, Chiba, Japan

Tel:+81 432262124,

Fax:+81 432244162

Email:Tarii@aol.com

Received Date: Jun 10, 2017

Accepted Date: Jul 18, 2017

Published Date: Aug 01, 2017

Abstract

Background: A Mantle Cell Lymphoma (MCL) is an aggressive B cell lymphoma and accounts for approximately 6% of all non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. A MCL has a poor prognosis with a median survival of about two to five years. We present our findings in a case of bilateral Central Retinal Vein Occlusion (CRVO) that developed in a patient with MCL.

Case Presentation: A 70-year-old woman was diagnosed with primary tonsil MCL in March 2009 and progressed to complete remission after chemotherapy. In March 2014, the decimal visual acuity in her right eye decreased to 0.01 due to a CRVO. Although malignant cells were not detected in the cerebrospinal fluid, methotrexate and dexamethasone were injected intraspinally. Two weeks later, the vision in her left eye decreased to 0.03, and she was found to have a CRVO in her left eye. Hematological and systemic evaluations eliminated hypercoagulability and autoimmune disorders. Although MRI and CT showed no central nervous infiltrations, the clinical features suggested that the CRVO was related to the recurrence of the lymphoma. She was treated with an intravitreal injection of anti-VEGF (aflibercept) and panrential photocoagulation. The macula edema improved and neovascular glaucoma was prevented. Her vision did not recover because of the retinal and optic nerve ischemia.

Conclusion: Bilateral CRVO can be associated with MCL although it is extremely rare. Nevertheless, clinicians should be aware of this association because a CRVO is a clinical sign of relapsing malignant ocular lymphoma.

Case Presentation: A 70-year-old woman was diagnosed with primary tonsil MCL in March 2009 and progressed to complete remission after chemotherapy. In March 2014, the decimal visual acuity in her right eye decreased to 0.01 due to a CRVO. Although malignant cells were not detected in the cerebrospinal fluid, methotrexate and dexamethasone were injected intraspinally. Two weeks later, the vision in her left eye decreased to 0.03, and she was found to have a CRVO in her left eye. Hematological and systemic evaluations eliminated hypercoagulability and autoimmune disorders. Although MRI and CT showed no central nervous infiltrations, the clinical features suggested that the CRVO was related to the recurrence of the lymphoma. She was treated with an intravitreal injection of anti-VEGF (aflibercept) and panrential photocoagulation. The macula edema improved and neovascular glaucoma was prevented. Her vision did not recover because of the retinal and optic nerve ischemia.

Conclusion: Bilateral CRVO can be associated with MCL although it is extremely rare. Nevertheless, clinicians should be aware of this association because a CRVO is a clinical sign of relapsing malignant ocular lymphoma.

Keywords

Central retinal vein occlusion; Chemotherapy; Mantle cell lymphoma; Relapsing

INTRODUCTION

A Mantle Cell Lymphoma (MCL) is an aggressive B cell lymphoma and accounts for approximately 6% of all Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphomas (NHLs) [1,2]. A MCL involves the lymph nodes, blood, spleen and bone marrow and has a poor prognosis with a median survival of about two to five years [3,4]. An intraocular involvement in cases of systemic lymphoma is rare, and when it occurs, it usually involves the uvea [5,6]. We report our findings in a patient with MCL who developed a Central Retinal Vein Occlusion (CRVO) in both eyes.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 70-year-old woman was diagnosed with primary tonsil MCL in May 2009 and progressed to complete remission after eight cycles of R-CHOP (Rituximab, Cyclophosphamide Hydroxydaunorubicin, Vincristine and Prednisone) chemotherapy. In July 2010, she had a recurrence of the lymphoma in the gastric mucous membrane, tonsils and pharynx but no additional treatment was given because she had no symptoms and the size of the tumors was small. In January 2014, metastases were detected in the cervical, supraclavicular and inguinal lymph nodes and the size of the tumors in the gastric mucous membrane, tonsils and pharynx were larger. However, the Central Nervous System (CNS) was not invaded as determined by fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computer tomography. Thus, a salvage therapy was instituted in April 2014. She had been diagnosed with Sjögren's syndrome in 2008 when the antiphospholipid antibody and the autoantibody were negative on blood tests. The medical condition was stabilized with an oral intake of 10mg of pilocarpine.

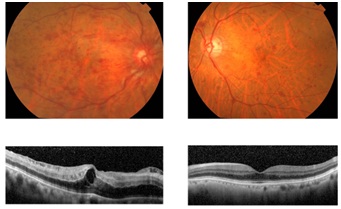

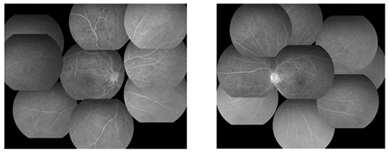

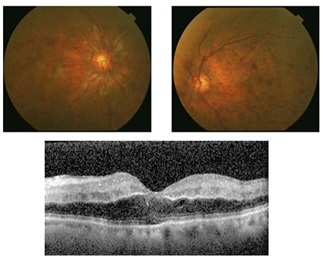

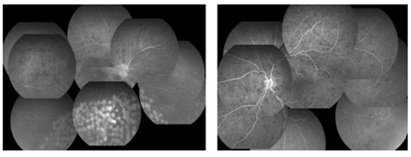

In March 2014, the vision in her right eye decreased, and two weeks later at the first visit to our hospital, the decimal Best-Corrected Visual Acuity (BCVA) was 0.01 OD and 1.0 OS. Slit-lamp biomicroscopy showed that the anterior segments and the anterior chamber angles were normal. The Intraocular Pressures (IOPs) were normal in both eyes. Fundus examination showed retinal hemorrhages and dilatation and tortuosity of the veins in all quadrants and cotton wool spots and macula edema in the right eye. A few widely-scattered, flame-shaped retinal hemorrhages and mild vascular tortuosity were present in the left eye. Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) showed cystoid macula edema in the right eye (Figure 1). Fluorescein angiography demonstrated a marked delay in the arteriovenous transit time, masking by the retinal hemorrhages, and late staining along the large retinal veins. A few non-perfused areas were also present in the right eye and a slight increase in retinal circulation time in the left eye (Figure 2).

In March 2014, the vision in her right eye decreased, and two weeks later at the first visit to our hospital, the decimal Best-Corrected Visual Acuity (BCVA) was 0.01 OD and 1.0 OS. Slit-lamp biomicroscopy showed that the anterior segments and the anterior chamber angles were normal. The Intraocular Pressures (IOPs) were normal in both eyes. Fundus examination showed retinal hemorrhages and dilatation and tortuosity of the veins in all quadrants and cotton wool spots and macula edema in the right eye. A few widely-scattered, flame-shaped retinal hemorrhages and mild vascular tortuosity were present in the left eye. Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) showed cystoid macula edema in the right eye (Figure 1). Fluorescein angiography demonstrated a marked delay in the arteriovenous transit time, masking by the retinal hemorrhages, and late staining along the large retinal veins. A few non-perfused areas were also present in the right eye and a slight increase in retinal circulation time in the left eye (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Fundus photographs (upper) and Optical Coherence Tomographic (OCT) images (lower) at the first visit.

Fundus photographs shows retinal hemorrhages, dilatation with tortuosity of the veins in all quadrants and cotton wool spots. Macular edema is present in the right eye (upper left) and a few widely-scattered, flame-shaped retinal hemorrhages and mild vascular tortuosity in the left eye (upper right). OCT images show cystoid macula edema in the right eye. In addition, the intraretinal edema and homogenous band-like thickening were found in the right eye.

Figure 2: Fluorescein angiograms at the first visit showing the central Retinal Vein Occlusion (CRVO) with several non-perfused areas in the right eye (left) and an impending CRVO in the left eye (right).

She was diagnosed with a right CRVO with macula edema and an impending CRVO in the left eye. An intravitreal ranibizumab injection was done on the right eye. Spinal puncture was performed by her primary physician to determine whether the CNS was involved but malignant cells were not detected in the Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF). Her hematologic profile and blood coagulation system such as platelets, lipids, prothrombin time, or activated partial thromboplastin time were normal, and an erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 16mm/hour. C-reactive protein and the autoantibody and cardiolipin antibody were negative. An intraspinal injection of methotrexate (15mg) and dexamethasone (4mg) and one cycle of the chemotherapy using bendamustine (90mg/mm2) were performed prophylactically.

Two weeks later, her BCVA decreased to 0.02 OD and 0.03 OS. Ophthalmoscopy showed that there was neovascularization on the optic disc of the right eye, and retinal hemorrhages and severe dilatation and tortuosity of the veins in all quadrants of the left eye. In addition, macula edema was detected in the left eye, and OCT showed cystoid macula edema in both eyes (Figure 3).

She was diagnosed with a right CRVO with macula edema and an impending CRVO in the left eye. An intravitreal ranibizumab injection was done on the right eye. Spinal puncture was performed by her primary physician to determine whether the CNS was involved but malignant cells were not detected in the Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF). Her hematologic profile and blood coagulation system such as platelets, lipids, prothrombin time, or activated partial thromboplastin time were normal, and an erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 16mm/hour. C-reactive protein and the autoantibody and cardiolipin antibody were negative. An intraspinal injection of methotrexate (15mg) and dexamethasone (4mg) and one cycle of the chemotherapy using bendamustine (90mg/mm2) were performed prophylactically.

Two weeks later, her BCVA decreased to 0.02 OD and 0.03 OS. Ophthalmoscopy showed that there was neovascularization on the optic disc of the right eye, and retinal hemorrhages and severe dilatation and tortuosity of the veins in all quadrants of the left eye. In addition, macula edema was detected in the left eye, and OCT showed cystoid macula edema in both eyes (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Fundus photographs (upper) and OCT images (lower) at two weeks after the first visit.

Fundus photographs show neovascularization on the optic disc of the right eye (upper left) and retinal hemorrhages and severe dilatation with tortuosity of veins and the macula edema in the left eye (upper right). The OCT image shows the cystoid macula edema and the intraretinal edema with homogenous band-like thickening of the left eye (lower).

We began Panretinal Photocoagulation (PRP) on the right eye to prevent Neovascular Glaucoma (NVG), and ranibizumab was injected intravitreally in the left eye on the same day. Fluorescein angiography showed delayed venous filling consistent with a CRVO with several non-perfused areas in the left eye (Figure 4). Magnetic resonance imaging was performed and no thickening of the optic nerve and no enhancement of the optic-nerve-sheath complex was detected in a post-contrast examination.

Figure 4: Fluorescein angiogram at 17 days after the first visit (upper) and the fundus photograph at 24 days after the first visit (lower).

The fluorescein angiograms show a CRVO with several non-perfused areas in both eyes. The fundus photograph shows retinal hemorrhages and venous dilatation, soft exudate in the left eye (lower).

Although there were only a small number of non-perfused areas in the fluorescein angiograms, we began PRP on the left eye to prevent the development of NVG. Although the causal relationship was weak between CRVO and MCL, we recommended further treatment for MCL to physicians because bilateral CRVO may be a clinical sign of a relapsing malignant ocular lymphoma. A second cycle of chemotherapy with bendamustine was performed by her primary physician. However, further chemotherapy was not done because of episodes of malaise and anorexia after the second cycle.

Later, we performed five intravitreal injections of aflibercept in each eye for the macula edema. The macula edema was well managed and NVG was prevented for the next 16 months. The decimal BCVA at 16 months after the onset was 0.03 OD and 0.02 OS and did not improve.

DISCUSSION

We report our findings in a rare case of MCL that developed CRVOs bilaterally. The ocular involvements in patients with NHL occurs most commonly in its primary form which is considered to be a subtype of primary CNS lymphomas [7,8]. However, an intraocular lymphoma secondary to systemic lymphoma is not common and is usually limited to the uveal tract [5,9]. There are several reports of the optic nerve involvement in cases of systemic NHL [10-12]. Several cases of infiltrative optic neuropathy have also been reported which may be the first manifestation of a recurrence of the NHL [11,13].

It is difficult to determine the exact route of the metastatic spread of a systemic NHL to the optic nerve because there are several possibilities, e.g., a direct invasion by the tumor cells, hematogenous dissemination, dissemination through the CSF, and perinueral spread to the optic nerve [14-16].

Several mechanisms are associated with the retinal vein occlusions in systemic NHL patients. There have been several reports of vascular occlusions secondary to a systemic NHL [7,17-19]. In one study, it was suggested that the vaso-occlusion was associated with the perivascular infiltration of lymphocytes through the laminacribosa sclerae which led to the vaso-occlusion [7]. It is also believed that vein occlusions are associated with compression of the vascular wall by the lymphomatous optic nerve infiltration in these studies. The findings in other reports suggested that the vascular occlusions were associated with septic emboli and with paraneoplastic hypercoagulability [17,20,21].

In our case, there was no evidence of septic emboli and of hypercoagulability. In addition, there were no positive images showing a thickening of the optic nerve with enhancement of the optic nerve-sheath complex, and no signs of metastasis to the CNS. Additionally, no lymphocytes were found the CSF. In earlier cases, most patients who had the optic nerve involvement with systemic diseases had positive neuroimaging with enhancement of the optic nerve or positivity for malignant cells in the CSF [10-12,16].

Although it is difficult to determine the etiology of the vaso-occlusions in our case, there is the possibility that the optic nerve infiltration could be associated with the vaso-occlusions. In our case, the visual acuity did not recover in spite of good management of the macula edema. In a previous case of a patient with NHL who developed central artery and retinal vein occlusions, it was suggested that these occlusions were due to optic nerve infiltration that led to bilateral posterior ischemic optic neuropathy according to postmortem examinations [17]. There is a possibility of posterior ischemic optic neuropathy which may have influenced the visual acuity in our case. Another possibility of poor visual acuities is the possibility of co-morbid central retinal artery occlusion because OCT findings showed significant intraretinal edema and homogenous band-like thickening.

After the on-label use of intravitreal aflibercept injection was permitted, intravitreal aflibercept injection becomes a first choice of the medical treatment for diabetic macular edema as well as RVO in our hospital [22]. Thu, we have switched from ranibizumab to aflibercept for the treatment of CRVO in this case.

From our experiences, in some cases it is difficult to control the IOP by performing PRP after the development of NVG. Thus, once we catch any signs of non-perfused areas, we start to perform PRP for preventing the development of NVG. For example, in case of management of diabetic retinopathy, we usually perform retinal photocoagulation for non-perfused areas in pre-proliferative diabetic retinopathy in Japan [23]. Thus, retinal photocoagulation for non-perfused areas is a standard therapy for diabetic retinopathy and RVO in Japan.

It is difficult to determine the exact route of the metastatic spread of a systemic NHL to the optic nerve because there are several possibilities, e.g., a direct invasion by the tumor cells, hematogenous dissemination, dissemination through the CSF, and perinueral spread to the optic nerve [14-16].

Several mechanisms are associated with the retinal vein occlusions in systemic NHL patients. There have been several reports of vascular occlusions secondary to a systemic NHL [7,17-19]. In one study, it was suggested that the vaso-occlusion was associated with the perivascular infiltration of lymphocytes through the laminacribosa sclerae which led to the vaso-occlusion [7]. It is also believed that vein occlusions are associated with compression of the vascular wall by the lymphomatous optic nerve infiltration in these studies. The findings in other reports suggested that the vascular occlusions were associated with septic emboli and with paraneoplastic hypercoagulability [17,20,21].

In our case, there was no evidence of septic emboli and of hypercoagulability. In addition, there were no positive images showing a thickening of the optic nerve with enhancement of the optic nerve-sheath complex, and no signs of metastasis to the CNS. Additionally, no lymphocytes were found the CSF. In earlier cases, most patients who had the optic nerve involvement with systemic diseases had positive neuroimaging with enhancement of the optic nerve or positivity for malignant cells in the CSF [10-12,16].

Although it is difficult to determine the etiology of the vaso-occlusions in our case, there is the possibility that the optic nerve infiltration could be associated with the vaso-occlusions. In our case, the visual acuity did not recover in spite of good management of the macula edema. In a previous case of a patient with NHL who developed central artery and retinal vein occlusions, it was suggested that these occlusions were due to optic nerve infiltration that led to bilateral posterior ischemic optic neuropathy according to postmortem examinations [17]. There is a possibility of posterior ischemic optic neuropathy which may have influenced the visual acuity in our case. Another possibility of poor visual acuities is the possibility of co-morbid central retinal artery occlusion because OCT findings showed significant intraretinal edema and homogenous band-like thickening.

After the on-label use of intravitreal aflibercept injection was permitted, intravitreal aflibercept injection becomes a first choice of the medical treatment for diabetic macular edema as well as RVO in our hospital [22]. Thu, we have switched from ranibizumab to aflibercept for the treatment of CRVO in this case.

From our experiences, in some cases it is difficult to control the IOP by performing PRP after the development of NVG. Thus, once we catch any signs of non-perfused areas, we start to perform PRP for preventing the development of NVG. For example, in case of management of diabetic retinopathy, we usually perform retinal photocoagulation for non-perfused areas in pre-proliferative diabetic retinopathy in Japan [23]. Thus, retinal photocoagulation for non-perfused areas is a standard therapy for diabetic retinopathy and RVO in Japan.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we report an extremely rare case of a patient with MCL who developed bilateral CRVO. Even when the causal relationship is weak between CRVO and MCL, ophthalmologists should recommend further therapies for MCL to physicians because a CRVO may be a clinical sign of a relapsing malignant ocular lymphoma.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This case study is supported by a Grant-in Aid from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of the Japanese Government. The authors thank Professor Duco Hamasaki for editing the manuscript. Written consent was obtained from the patient for publication of study.

REFERENCES

- Kauh J, Baidas SM, Ozdemirli M, Cheson BD (2003) Mantle cell lymphoma: clinicopathologic features and treatments. Oncology (Williston Park) 17: 879-898.

- No authors listed] (1997) A clinical evaluation of the International Lymphoma Study Group classification of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. The Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Classification Project. Blood 89: 3909-3918.

- Vose JM (2013) Mantle cell lymphoma: 2013 Update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and clinical management. Am J Hematol 88: 1082-1088.

- Ghielmini M, Zucca E (2009) How I treat mantle cell lymphoma. Blood 114: 1469-1476.

- Qualman SJ , Mendelsohn G, Mann RB, Green WR (1983) Intraocular lymphoma Natural history based on a clinicopathologic study of eight cases and review of the literature. Cancer 52: 878-886.

- Nelson CC, Hertzberg BS, Klintworth GK (1983) A histopathologic study of 716 unselected eyes in patients with cancer at the time of death. Am J Ophthalmol 95: 788-793.

- Lee LC, Howes EL, Bhisitkul RB (2002) Systemic non-Hodgkin's lymphoma with optic nerve infiltration in a patient with AIDS. Retina 22: 75-79.

- Fend F, Ferreri AJ, Coupland SE (2016) How we diagnose and treat vitreoretinal lymphoma. Br J Haematol 173: 680-692.

- Mashayekhi A, Shields CL, Shields JA (2013) Iris involvement by lymphoma: a review of 13 cases. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 41: 19-26.

- Finke E, Hage R, Donnio A, Bomahou C, Guyomarch J, et al. (2012) Retrobulbar optic neuropathy and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. J Fr Ophtalmo l35: 124.

- Kay MC (1986) Optic neuropathy secondary to lymphoma. J Clin Neuroophthalmol 6: 31-34.

- Kim UR, Shah AD, Arora V, Solanki U (2010) Isolated optic nerve infiltration in systemic lymphoma-a case report and review of literature. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 26: 291-293.

- Siatkowski RM, Lam BL, Schatz NJ, Glaser JS, Byrne SF, et al. (2002) Optic neuropathy in Hodgkin's disease. Retina 22: 75-79.

- Christmas NJ, Mead MD, Richardson EP, Albert DM (1991) Secondary optic nerve tumors. Surv Ophthalmol 36: 196-206.

- Weber AL, Caruso P, Sabates NR (2005) The optic nerve: radiologic, clinical, and pathologic evaluation. Neuroimaging Clin N Am 15: 175-201.

- Kim JL, Mendoza PR, Rashid A, Hayek B, Grossniklaus HE (2015) Optic nerve lymphoma: report of two cases and review of the literature. Surv Ophthalmol 60: 153-165.

- Guyer DR, Green WR, Schachat AP, Bastacky S, Miller NR (1990) Bilateral ischemic optic neuropathy and retinal vascular occlusions associated with lymphoma and sepsis. Clinicopathologic correlation. Ophthalmology 97: 882-888.

- Shukla D, Arora A, Hadi KM, Kumar M, Baddela S, et al. (2006) Combined central retinal artery and vein occlusion secondary to systemic non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Indian J Ophthalmol 54: 204-206.

- Saatci AO, Düzovali O, Ozbek Z, Saatci I, Sarialioglu F (1998) Combined central retinal artery and vein occlusion in a child with systemic non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Int Ophthalmol 22: 125-127.

- Kling F, Macarez R, Robinet A, Kouassi FX, Colin J (1999) Mixed retinal thrombosis in a patient carrying prothrombin gene mutation in a homozygote state. J Fr Ophtalmol 22: 979-981.

- . Yoshida A, Watanabe M, Ohmine K, Kawashima H (2015) Central retinal vein occlusion caused by hyperviscosity syndrome in a young patient with Sjögren's syndrome and MALT lymphoma. Int Ophthalmol 35: 429-432.

- Shimizu N, Oshitari T, Tatsumi T, Takatsuna Y, Arai M, et al. (2017) Comparisons of efficacy of intravitreal aflibercept and ranibizumab in eyes with diabetic macular edema. BioMed Res Int ID1747108.

- Japanese Society of Ophthalmic Diabetology, Subcommittee on the Study of Diabetic Retinopathy Treatment, Sato Y, Kojimahara N, Kitano S, Kato S, et al. (2012) Multicenter randomized clinical trial of retinal photocoagulation for preproliferative diabetic retinopathy. Jpn J Ophthalmol 56: 52-59.

Citation: Furuya N, Oshitari T, Sato E, Baba T, Yamamoto S (2017) Bilateral Central Retinal Vein Occlusion in a Patient with Mantle Cell Lymphoma. J Ophthalmic Clin Res 4: 031.

Copyright: © 2017 Nana Furuya, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

© 2026, Copyrights Herald Scholarly Open Access. All Rights Reserved!