Craniopharyngioma: A Benign Brain Tumor

*Corresponding Author(s):

Anestakis DDepartment Of Autopsy Histopathology, Laboratory Of Forensic And Toxicology, Aristotle University Of Thessaloniki, Greece

Tel:+30 2310999205,

Email:anestaki@auth.gr

Abstract

Craniopharyngioma is one rare slowly developing, usually benign tumor. In majority of cases, such tumors grow above the anterior upper lip of hypophysis and are located mainly on Turkish sella or on side sella areas. According to opidimiology data, they are relatively rare tumors with incidence of 0,12-2 people per 100.000 people a year and they constitute the 2-5% of all brain tumors. Such tumors are connected with a plethora of symptoms from the central nervous system, endocrinium system and eyes, especially unpleasant, annoying and dangerous if not treated in time. Histologically, two types adamantionomatous and papillary type have been ascertained (though they have ascertained and mixed types). However, regardless of their main type, they usually have cystical form. The size of craniopharyngioma is between 2 to 4 cm (it seldom grows over 12 cm). The most usually showings are neurological, endocrinological symptoms and disorder of vision. With regard to the diagnosis of craniopharyngioma, it depends on clinical and radiological finds and it is confirmed by histological examination. The most usual and the most efficient technique for treatment is total surgical removal

accompanied by radiotherapy. Nonetheless, after every therapy, there is the danger of many complications like pituitary insufficiency and the development diabetes in sipidus.

INTRODUCTION

Macroscopically, they are seemed as big globe tumors with white or red-blooded surface [1-4]. Histologically, have ascertained two types, adamantinomatous and papillary type (though they have ascertained and mixed types). However, independently of their main type, they usually have cystical form. The size of craniopharyngioma is between 2 to 4 cm. Strike 0,12-2/100.000 people a year, 30 to 50% of all cases presenting during childhood and adolescence and they constitute the 2 to 5% of all brain tumors [5]. The peak incidence rates have been shown in children of ages 5 to 14 years and adults of ages 50 to 74 years [6]. Despite their benign nature, craniopharygioma are prone to infiltrative growth. This occurs due to focal invasion of individual epithelial aggregates to the adjacent brain tissue.

PATHOLOGY

There are two craniopharyngioma subtypes: adamantinomatous and papillary [7]. However, there have been found and mixed types too [8]. Adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma is recognized by the presence of squamous epithelium disposed in cords, nodules, and irregular trabeculae bordered by palisaded columnar epithelium. Cystic cavities containing squamous debris are lined by flattened epithelium. From the other side, three essential features of the second subtype (papillary craniopharyngioma) include a monomorphous mass of well-differentiated squamous epithelium lacking surface maturation, the picket fence-like palisades and wet keratin. As noted, another contrasting point is the absence of calcification. Only rarely are ciliated epithelium and goblet cells encountered. Generally, vascular malformation in the tumor due to proliferation and migration of endothelial cells are one of the key possible mechanisms that explain the aggressive behavior of craniopharygioma.

MORPHOLOGY

Only 10% of craniopharygioma have a completely solid structure. The remaining 90% of tumors are characterized by the formation of cysts with different volume. In 60% of craniopharygioma, the cystic component predominates with respect to its volume. Adamantinomatous craniopharygioma predominantly occur among children, young people and, less frequently, in elderly people. The histological presentation includes growth of epithelial cells that form bundles of trabecules and round aggregates. The appearance of epithelium differs depending on its localization: the basal layer adjacent to the connective tissue is formed by a single layer of oval cells; the further epithelial cells are less ordered. This craniopharygioma variant is frequently associated with the development of ceratoid degeneration, formation of horny lamellae and giant-cell granulomas of foreign bodies. The calcification and ossification phenomena are quite typical. Unlike adamaninomatouscraniopharygioma, papillary craniopharygioma occur in adults, have a more compact solid structure, and are less likely to contain cysts and petrificates. Papillary craniopharygioma are formed by well-differentiated epithelium. The layers of stratified non-keratinized squamous epithelium are separated by a loose connective tissue stroma containing a large number of vessels. The mutual arrangement of the stroma and epithelial layers forms papillary structures that are morphologically similar to squamous cell papilloma.

PATHOGENESIS

There are two theories about pathogenis, Embryonic and Metaplastic.

A. Embryonic

Adamantinomatous craniopharyngiomas arise from neoplastic transformation of embryonic squamous cell nests of the involutedcraniopharyngeal duct that initially connects Rathke’s pouch with the stomodeum. During the process of the formation of the adenohypophysis, cell remnants of the craniopharyngeal duct are spread through the intrasellar and suprasellar region. Resulting in a spread of cells of the craniopharyngeal duct to the suprasellar region, which is the most frequent location of craniopharyngiomas.

B. Metaplastic

Papillary craniopharyngiomas are the result of metaplasia of the adenohypophyseal cells in the pars tuberalis of the adenohypophysis, resulting in the formation of squamous cell nests. This theory is supported by the presence of metaplastic nests in the gland (increasing with age) and of hormones contained in the squamous nests.

BIOLOGY BACKGROUND

To begin with, mutant D32Y, G34R, and G34V genes, which occur in some skin neoplasms were detected in epithelial cells of craniopharygioma. Craniopharygioma are monoclonal tumors that are formed after activation of oncogenes localized in certain chromosomal loci. Moreover, Ki-67 protein is a marker of cell proliferation. The Ki-67 labeling indices (MIB-1 clone, which is a clone of anti-Ki-67 antibody) in epithelial cells were found to be higher than those in the tumor stroma. Also, beta-catenin is accumulated in adamantinomatous craniopharygioma in nuclei or the cytoplasm of the cohesive cells localized in the con- centric foci and in cells that can be transformed to the ghost cells (that never express Ki-67) [9]. Adamantinomatous craniopharygioma and papillary craniopharygioma differ clinically, morphologically, and genetically as well. The mutant beta-catenin gene was detected only in adamantinomatous craniopharygioma. In all the cases, betacatenin was accumulated both in the cytoplasm and cellular nuclei of these tumors. Papillary craniopharygioma are characterized by the mem- brane expression of beta-catenin only. In addition, the mutant beta-catenin gene was detected both in the epithelial and mesenchymal cells of adamantinomatous craniopharygioma, which attests the biphasic nature of these tumors.

LOCATION

Craniopharyngiomas can arise anywhere along the craniopharyngeal canal, but most of them occur in the sellar/ parasellar region and especially, they grow above the anterior upper lip of pituitary gland and they are located mainly on sellaturcica.

DIAGNOSIS

Both computerized tomography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) reveal that craniopharyngioma is typically a cystic tumor of the intra and/or suprasellar region. The most common localization is suprasellar, with an intrasellar portion; only 20% are exclusively suprasellar, and even less (5%) are exclusively intrasellar. Computerized tomography is the only way to definitively detect or exclude calcifications in craniopharyngioma tissue, which is found in approximately 90% of these tumors. However, a histological examination is always necessary to confirm a craniopharygioma. The diagnosis of childhood craniopharyngioma is often made late sometimes years after the initial appearance of symptoms with a clinical picture at the time of diagnosis often dominated by nonspecific manifestations of intracranial pressure (eg, headache and nausea). Further primary manifestations are visual impairment (62-84%) and endocrine deficits (52-87%) and other endocrine symptoms such as neurohormonal diabetes insipidus. At last many researchers have revealed that a pathologically reduced growth rate presents in patients as young as 12 months.

There are a lot of diagnostic indicators for both adamantinomatous and papillary craniopharyngioma. One of them is Ki-67 protein, which is a marker of cell proliferation. The Ki-67 labeling indices in epithelial cells were found to be higher than those in the tumor stroma. Two other proteins are p53 and p63 protein. The p53 protein, which participates in DNA repair processes and in regulation of transcription of the genes regulating apoptosis, induces apoptosis when its level is increased, in response to DNA damage. The p63 protein participates in regulation of adhesion and viability of epithelial cells. Both of them are detected in adamantinomatous and papillary craniopharyngioma. The p53 in expression of its mutant form and p63 in increased levels. Specifically, the presence of concentric foci of epithelial cells in the tumor and high level of p53 expression reliably correlate with the risk of continues growth and probability of relapse .

Some other indicators are the mutant D32Y, G34R and G34V genes, which occur in some skin neoplasms and they were detected in epithelial cells of craniopharyngioma. Also, beta-cetanin is accumulated in adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma in nuclei or the cytoplasm of the cohesive cells localized in the concentric foci and in cells that can be transformed to the ghost cells that never express Ki-67. In a similar manner, LEF1 is heterogeneously expressed in adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma. LEF1 is a protein factor, which gives rise to teeth enamel, is expressed only in teeth and plays a significant role in teeth development along with beta-cetanin. Adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma is characterized by odontogenic epithelial differentiation. Different levels of expression of enamel proteins, like amelogenin, enamelin and enamelysin, are observed in all adamantinomatous craniopharyngiomas, predominantly in the ghost cells. In craniopharyngioma with rapid recurrence is detected expression of some cytokeratins, CK8, CK18 and CK19 in more than half of the tumors and a decreased galectin-3 level.

From the other side, there are a lot of techniques to use for treatment like radical surgical ablation, cystical fluid suction, intraciscient radiotherapy or a combination of previous techniques. The most usual and efficient technique for treatment is total surgical removal accompanied by radiotherapy. However, for unfavorably localized tumors too close to or too entangled with the optic nerve and/or the hypothalamus, controversy exists over whether complete resection should still be attempted or whether a planned limited resection. Nonetheless, after every therapy, there is the danger of many complications like pituitary insufficiency and the development diabetes insipidus. Therefore, the quality of life, evaluated in different scales, is not especially good due to pituitary insufficiency while, impacts as fatigue and reduced exercise, night sleep disorder and obesity, are not so rare.

TREATMENT

There are a lot of possible treatment strategies for craniopharygioma. Such strategies are transcranial approach with suprasellar extension and transsphenoidal approach, which is a surgical access strategy, as far as the neurosurgery is concerned. Also, regarding the irradiation, there are the conventional external radiotherapy, the proton beam therapy, the radiosurgery, the intracavitaryβ-irradiation and the stereotactic radiotherapy which combines the accurate focal dose delivery of stereotactic radiosurgery with the radiobiological advantages of fractionation [10]. Specifically, the preferred treatment of choice especially at primary craniopharygioma diagnosis is an attempt at complete resection with preservation of visual, hypothalamic and pituitary function. Also, irradiation is effective in preventing progression of residual tumor and a recommended treatment option in case of limited surgical perspectives with regard to hypothalamus-sparing aspects. It is a fact that, recent studies showing that radical gross total resection in craniopharygioma with hypothalamic involvement is associated with recurrence rates similar to progression rates after limited surgery, resulting in residual tumor [11]. To conclude with, at the time point of initial diagnosis, the decision about treatment strategy should be made by a multidisciplinary team within the context of recognized potential risk factors and a treatment plan for postoperative follow-up and rehabilitation.

LONG TERM OUTCOME

Pituitary hormone deficiencies are common in craniopharyngioma. The rate of postsurgical pituitary hormone deficiencies increases due to the tumor’s proximity or even involvement with the hypothalamic-pituitary axes. Transient postsurgical diabetes insipidus occurs in up to 80 to 100% of all cases [12]. Symptoms related to hypothalamic dysfunction, such as obesity, behavioral changes, disturbed circadian rhythm, sleep irregularities, daytime sleepiness, and imbalances in regulation of body temperature, thirst, heart rate, and/or blood pressure have been found at diagnosis in 35% of childhood craniopharyngioma patients. Rapid weight gain and severe obesity are the most perplexing complications due to hypothalamic involvement and/or treatment-related hypothalamic damage in craniopharyngioma patients. Weight gain in childhood craniopharyngioma patients often occurs years before diagnosis. Markedly increased daytime sleepiness and disturbances of circadian rhythms have been demonstrated in patients with and severe obesity. Hypothalamic disinhibition of vagal output is a cause of increased cell stimulation in patients with craniopharyngioma and that this disinhibition leads to hyperinsulinism and severe obesity. Quality of life in craniopharyngioma patients can be affected by both the tumor itself and the treatment received. Such outcomes are, somatic complaints such as reduced mobility, pain, and self-care. Long-term neurocognitive complications after treatment for craniopharyngioma include cognitive problems, particularly those affecting executive function, attention, episodic memory, and working memory.

SURVIVAL RATE

The overall survival rates described in exclusive children series range from 83 to 96% at 5 years and average 62% at 20 years [13]. In adults or a mixed-age-range population (adults and children) series, the overall survival rates range from 54 to 96% at 5 years from 40 to 85% at 20 years [14]. Disease-related mortality can even occur many years after treatment. Causes of late mortality include those directly related to the tumor or its treatment such as progressive disease with multiple recurrences, chronic hypothalamic insufficiency, hormonal deficiencies, cerebrovascular disease and seizures.

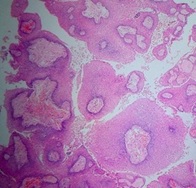

Figure 1: Papillary craniopharyngioma. Non-keratinized squamous epithelium (without nuclear atypia) and fibrovascular cores.

Figure 1: Papillary craniopharyngioma. Non-keratinized squamous epithelium (without nuclear atypia) and fibrovascular cores.

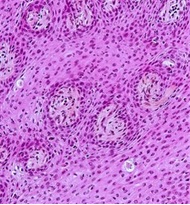

Figure 2: Papillary craniopharyngioma. The tumor has a cauliflower-like appearance, with surface epithelium covering central fibro vascular cores.

Figure 2: Papillary craniopharyngioma. The tumor has a cauliflower-like appearance, with surface epithelium covering central fibro vascular cores.

CONCLUSION

Such tumors are connected with a lot of symptoms from the central nervous system, endocrine system and eyes. Its size is 2-4cm. The diagnosis depends on clinical and radiological finds and it is confirmed by histological examination (Figure 1-2). Specifically, it’s done with simple X-ray of Sella Turcica, CT, MRI and occasionally with brain angiography. From the other side, there are a lot of techniques to use for treatment like radical surgical ablation, cystical fluid suction, intraciscient radiotherapy or a combination of previous techniques. The most usual and efficient technique for treatment is total surgical removal accompanied by radiotherapy. Nonetheless, after every therapy, there is the danger of many complications like pituitary insufficiency and the development diabetes insipidus. Therefore, the quality of life, evaluated in different scales, is not especially good due to pituitary insufficiency while, impacts as fatigue and reduced exercise, night sleep disorder and obesity, are not so rare.

REFERENCES

- Petito CK, De Girolami U, Earle K (1976) Craniopharyngiomas: A clinical and pathological review. Cancer 637: 1944-1952. ?

- Crotty TB, Scheithauer BW, Young WF, Davis DH, Shaw EG, et al., (1995) Papillary craniopharyngioma: A clinico-pathological study of 48 cases. J Neurosurg 83: 206-214. ?

- Eldevik OP, Blaivas M, Gabrielsen TO, HaldJK, Chandler WF, et al., (1996) Craniopharyngioma: Radiologic and histologic findings and recurrence. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 17: 1427-1439.

- Muller L (2014) Endocrine Reviews 35: 513-543.

- Bunin GR, Surawicz TS, Witman PA, Preston-Martin S, Davis F, et al., (1998) The descriptive epidemiology of craniopharyngioma. J Neurosurg 89: 547-551.

- Haupt R, Magnani C, Pavanello M, Caruso S, Dama E, et al., (2006) Epidemiological aspects of craniopharyngioma. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 19: 289-293.

- Sartoretti Schefer S, Wichmann W, Aguzzi A, Valavanis A (1997) MR differentiation of adamantinous and squamous-papillary craniopharyngiomas. Am J Neuroradiol 18: 77-87.

- Muller DC (1994) Pathology of craniopharyngiomas: clinical import of pathological findings. Pediatr Neurosurg 21: 11-1

- Kutin MA, Rotin DL, Shishkina LV, Kadeshev BA (2013) Current Opinion on Craniopharyngioma Biology. Journal of Neurosurgery. Page no: 48-56.

- Honegger J, Buchfelder M, Fahlbusch R (1999) Surgical treatment of craniopharyngiomas: endocrinological results. J Neurosurg 90: 251-257.

- Fahlbusch R, Honegger J, Paulus W, Huk W, Buchfelder M, et al., (1999) Surgical treatment of craniopharyngiomas: experience with 168 patients. J Neurosurg 90: 237-250.

- Dekkers OM, Biermasz NR, Smit JW, Groot LE, Roelfsema F, et al., (2006) Quality of life in treated adult craniopharyngioma patients. Eur J Endocrinol 154: 483-489.

- Karavitaki N, Brufani C, Warner JT (2005) Craniopharyngiomas in children and adults: systematic analysis of 121 cases with long-term follow-up. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf ) 62: 397-409.

- Weiner HL, Wisoff JH, Rosenberg ME (1994) Craniopharyngiomas: A clinicopathological analysis of factors predictive of recurrence and functional outcome. Neurosurgery 35: 1001-1011.

Citation: Doxakis A, Vasileios C, FountaIoanna K, Polyanthi K, Drosos T, et al. (2019) Craniopharyngioma: A Benign Brain Tumor. Forensic Leg Investig Sci 5: 037.

Copyright: © 2019 Anestakis D, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.