Criminal Provisions for Human Trafficking: Rankings, State Grades, and Challenges

*Corresponding Author(s):

Meshelemiah JCACollege Of Social Work, The Ohio State University, Columbus, United States

Tel:+1 6142929887,

Email:Meshelemiah.1@osu.edu

Abstract

The purpose of the Trafficking Victims Protection Act at the federal level is to enhance the government’s capacity to provide protection, prevention, and prosecution involving the crime of human trafficking of adults and children. The purpose of this paper is to explore the criminal provisions related to human trafficking at the state level. All 50 states and Washington DC have human trafficking laws. Some fare better than others. The author discusses how U.S. states are meeting or failing to meet the basic legal requirements for a comprehensive anti-trafficking framework. Recommendations on how to take more steps to improve and implement laws are offered.

Keywords

Criminal provisions; Domestic minor sex trafficking; Grade; Human trafficking traffickers

INTRODUCTION

Criminal provisions for human trafficking are important first steps in eradicating modern day slavery. Federal and state level criminal provisions have been enacted in the U.S. since 2000 at the federal level and 2003 at the state level beginning with the state of Washington. Human trafficking persists, however, despite the federal and state laws enacted to criminalize trafficking in persons1. The Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act was first enacted in 2000 and has been reauthorized several times since then [2-7]. The Act is best known for its’ section on severe human trafficking, which is known as the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA). According to the TVPA, severe human trafficking activities are primarily categorized as sex trafficking or labor trafficking. Sex trafficking is “the recruitment, harboring, transportation, provision, or obtaining of a person for the purpose of a commercial sex act (CSA), in which a CSA is induced by force, fraud, or coercion, or in which the person induced to perform such act has not attained 18 years of age”, while labor trafficking is defined as “the recruitment, harboring, transportation, provision, or obtaining of a person for labor or services, through the use of force, fraud, or coercion, for the purpose of subjection to involuntary servitude, peonage, debt bondage, or slavery”. Minors are legally treated differently than adults according to the provisions of the TVPA as shown in the definition of sex trafficking. Force, fraud or coercion are not necessary elements for those less than 18 years of age who engage in commercial sex given their minor status [8]. Due to the minor’s unique vulnerability and age, Shared Hope International, coined the term, domestic minor sex trafficking (DMST), to describe the sexual exploitation of American children within the U.S. borders. DMST is also known by other names that include child sex slavery, child sex trafficking, prostitution of children, and commercial sexual exploitation of children (CSEC) [9].

The purpose of the Trafficking Victims Protection Act is to enhance the government’s capacity to provide protection, prevention, and prosecution involving the crime of human trafficking of adults and children. The purpose of this paper is to explore the criminal provisions related to human trafficking and how U.S. states are meeting or failing to meet the basic legal requirements for a comprehensive anti-trafficking framework. The author will discuss how to take more steps to improve and implement laws.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Due to the clandestine nature of human trafficking, researchers rely on estimates and proxies when determining the prevalence of human trafficking activities in the U.S. as well as around the globe. According to the International Labour Organization and Walk Free Foundation [10], 89 million people experienced some form of slavery (a.k.a. human trafficking) in the past five years. The Global Slavery Index estimates it to be at least 40 million in current time [11]. While there is no official estimate of the total number of people who are trafficked in the U.S., Polaris estimates the actual number of victims to be in the hundreds of thousands when sex and labor trafficking estimates are aggregated for adults and minors. Since 2007, Polaris has handled 51,919 U.S. trafficking cases. In 2018 alone, the National Human Trafficking Hotline [operating out of Polaris] received 28,335 phone calls; 5,197 texts; 1566 web chats; 4,034 web forms, and 1,956 emails. These 41,088 contacts involved 10,949 cases, 5,859 potential traffickers, 1,905 suspicious businesses, and 23,078 survivors identified. Survivors who indicated race/ethnicity were Latino (n=2,348); Asian (n=1,809); African American/Black (n=1,072); White (n=989); and multi-racial (n=184). Clusters of trafficking included: sex trafficking, labor trafficking, and combined sex and labor trafficking. These statistics illustrate the depth and breadth of reported human trafficking activities in the U.S. as well as the extent to which interventions-especially those originating in the legal system are needed to comprehensively address it at the state level throughout the U.S.

STATE LAWS

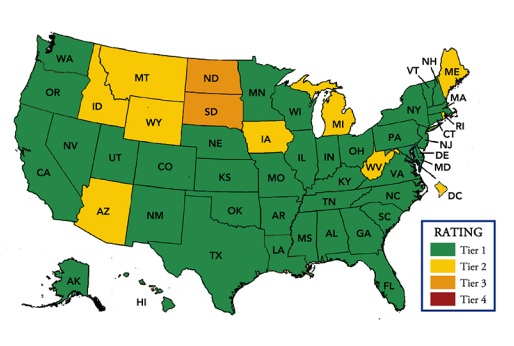

As of July 31, 2014, 39 out of 50 U.S. states were rated Tier I, which indicates that significant human trafficking laws had been passed in those states and that the states should continue to improve efforts and implement existing laws. Only three states, Delaware, New Jersey, and Washington, were rated with a perfect score due to their adherence to all 10 categories of laws that are deemed critical to a basic legal framework for combatting human trafficking. The state of Washington is a consistent leader in the fight to end trafficking as the first state to criminalize human trafficking in 2003 [12] (Figure 1).

Figure 1: 2014 State Ratings on Human Trafficking Laws.

According to Polaris, the categories of law that are deemed critical to a basic legal framework for combatting human trafficking include:

- Sex trafficking [a statute that criminalizes sex trafficking and its elements of force, fraud, or coercion to engage in commercialized sex].

- Labor trafficking [a statute that criminalizes behaviors that compel a person to provide labor or services through force, fraud, or coercion].

a) Asset forfeiture for Human Trafficking [a statute that amends the Racketeer Influential and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act statutes so that forfeiture of assets acquired with proceeds or used in the course of human trafficking are included] and b) Investigative tools for law enforcement[a statute that amends the Racketeer Influential and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act statutes so that wiretapping by law enforcement is permitted during human trafficking investigations].

a) Training on human trafficking for law enforcement [a statute that requires or encourages law enforcement officers to become educated on human trafficking] and b) Human trafficking commission or task force [a statute that creates, establishes or encourages the creation of any of the following: A commission, task force or advisory committee on human trafficking]. - Lower burden of proof for sex trafficking of minors [a statute that aligns with the federal level Trafficking Victims Protection Act that eliminates the need for minors who are sex trafficked to show proof of force, fraud, or coercion].

- Posting a human trafficking hotline [a statute that encourages or requires the public posting of a human trafficking hotline number that is run at the state level or national level (e.g., National Human Trafficking Resource Center hotline that is run by Polaris)].

- Safe harbor: Protecting sexually exploited minors [a statute that includes immunity from prosecution or diversion and welfare services for the child victim].

- Victim assistance [a statute that provides assistance, requires the creation of a formal plan for victim services, or funds actual programming for trafficked persons.]

- Access to civil damages [a statute that allows trafficked victims to sue their traffickers and pursue civil damages.]

- Vacating convictions for sex trafficking victims [a statute that permits prostitution convictions to be vacated when the prostitution was the result of sex trafficking]

As shown in these 10 categories of laws that are deemed critical to a basic legal framework for combating human trafficking, fighting human trafficking requires a systematic, multi-prong, aggressive and multilayered approach from informed legislators, law enforcement agencies, forensic interview specialists, prosecutors, defense attorneys, judges, civil liberties unions, building code inspectors, community members, task force members, advisory groups, marketing campaign organizations, victim services organizations, and child welfare/social service agencies. As shown, not all states have been successful at incorporating statutes that fall under all 10 categories of law. This leaves a gap in anti-trafficking efforts and the convictions of traffickers and facilitators. For instance, North Dakota and South Dakota were ranked Tier 3 in 2014, which means that the two states had only made nominal efforts to pass laws to combat human trafficking and should work to improve and implement laws. Arizona, Washington DC, Idaho, Iowa, Maine, Michigan, Montana, Rhode Island, West Virginia, and Wyoming were all ranked Tier 2, which means that they had passed several anti-trafficking laws, but they should take more steps to improve and implement laws [13].

CONVICTIONS

One of the purposes of statutes that criminalize human trafficking is to prosecute traffickers and facilitators. In fiscal year 2016, Homeland Security Investigations (HIS), which are carried out through Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), “initiated 1,029 investigations with a nexus to human trafficking and recorded 1,952 arrests, 1,176 indictments, and 631 convictions; 435 victims were identified and assisted” [14] . In fiscal year 2018, the Department of Justice initiated 230 human trafficking prosecutions, charged 386 defendants, and convicted 526 defendants. The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), initiated 649 human trafficking cases and arrested 2453 suspects that resulted in 410 convictions and 422 sentencing in the same fiscal year [15]. These prosecutions have been made possible due to an increased number of laws that have been enacted to ensure a greater number of punitive measures against perpetrators. For example, Colorado, California, and Virginia have new laws that specifically aid in prosecution; South Carolina, Arizona, and West Virginia have new laws that prohibit certain defenses for perpetrators; Rhode Island, South Carolina, Missouri, and West Virginia have new laws that prosecute businesses involved in trafficking; and Hawaii, Missouri, Maine, and New Jersey have new laws that expand the scope of prosecution to facilitators [16].

LEGISLATIVE FRAMEWORK FOR DOMESTIC MINOR SEX TRAFFICKING

In an effort to delineate between criminal provisions for trafficking of adults vs children, the Protected Innocence Challenge offers a framework for comprehensively responding to domestic minor sex trafficking in the 50 states and Washington DC. The legislative framework contains six core areas made up of 41 components and has been used to grade a state’s progress (but not enforcement or implementation) in enacting human trafficking laws for minors in these core areas. Table 1 Ranking states involves assigning points ranging from <60 points up to 102.5 and resulting in A, B, C, D, and F grades. The following six components make up the 41 legal components [17]:

- Criminalization of Domestic Minor Sex Trafficking

- Criminal Provisions with Addressing Demand

- Criminal Provisions for Traffickers

- Criminal Provisions for Facilitators

- Protective Provisions for the Child Victim

- Criminal Justice Tools for Investigation and Prosecution

|

Section 1: Criminalization of Domestic Minor Sex Trafficking (Legal Components) |

|

|

1.1 |

The state human trafficking law addresses sex trafficking and clearly defines a human trafficking victim as any minor under the age of 18 used in a commercial sex act without regard to use of force, fraud, or coercion, aligning to the federal trafficking law. |

|

1.2 |

Commercial sexual exploitation of children (CSEC) is identified as a separate and distinct offense from general sexual offenses, which may also be used to prosecute those who commit commercial sex offenses against minors. |

|

1.3 |

Prostitution statutes refer to the sex trafficking statute to acknowledge the intersection of prostitution with trafficking victimization. |

|

1.4 |

The state racketeering or gang crimes statute includes sex trafficking or commercial sexual exploitation of children (CSEC) offenses as predicate acts allowing the statute to be used to prosecute child sex trafficking crimes. |

|

Section 2: Criminal Provisions Addressing Demand (Legal Components) |

|

|

2.1 |

The state sex trafficking law can be applied to buyers of commercial sex acts with a minor. |

|

2.2 |

Buyers of commercial sex acts with a minor can be prosecuted under commercial sexual exploitation of children (CSEC) laws. |

|

2.3 |

Solicitation laws differentiate between soliciting sex acts with an adult and soliciting sex acts with a minor under 18. |

|

2.4 |

Penalties for buyers of commercial sex acts with minors are as high as federal penalties. |

|

2.5 |

Using the Internet or electronic communications to lure, entice, or purchase, or attempt to lure, entice, or purchase commercial sex acts with a minor is a separate crime or results in an enhanced penalty for buyers. |

|

2.6 |

No age mistake defense is permitted for a buyer of commercial sex acts with any minor under 18. |

|

2.7 |

Base penalties for buying sex acts with a minor under 18 are sufficiently high and not reduced for older minors. |

|

2.8 |

Financial penalties for buyers of commercial sex acts with minors are sufficiently high to make it difficult for buyers to hide the crime. |

|

2.9 |

Buying and possessing images of child sexual exploitation carries penalties as high as similar federal offenses |

|

2.10 |

Convicted buyers of commercial sex acts with minors are required to register as sex offenders. |

|

Section 3: Criminal Provisions for Traffickers (Legal Components) |

|

|

3.1 |

Penalties for trafficking a child for sexual exploitation are as high as federal penalties. |

|

3.2 |

Creating and distributing images of child sexual exploitation carries penalties as high as similar federal offenses. |

|

3.3 |

Using the Internet or electronic communications to lure, entice, recruit or sell commercial sex acts with a minor is a separate crime or results in an enhanced penalty for traffickers. |

|

3.4 |

Financial penalties for traffickers, including asset forfeiture, are sufficiently high. |

|

3.5 |

Convicted traffickers are required to register as sex offenders. |

|

3.6 |

Laws relating to parental custody and termination of parental rights include sex trafficking or commercial sexual exploitation of children (CSEC) offenses as grounds for sole custody or termination in order to prevent traffickers from exploiting their parental rights as a form of control. |

|

Section 4: Criminal Provisions for Facilitators (Legal Components) |

|

|

4.1 |

The acts of assisting, enabling, or financially benefitting from child sex trafficking are included as criminal offenses in the state sex trafficking statute. |

|

4.2 |

Financial penalties, including asset forfeiture laws, are in place for those who benefit financially from or aid and assist in committing domestic minor sex trafficking. |

|

4.3 |

Promoting and selling child sex tourism is illegal. |

|

4.4 |

Promoting and selling images of child sexual exploitation carries penalties as high as similar federal offenses. |

|

Section 5: Protective Provisions for Child Victims (Legal Components) |

|

|

5.1 |

Victims under the core child sex trafficking offense include all commercially sexually exploited children. |

|

5.2 |

The state sex trafficking statute expressly prohibits a defendant from asserting a defense based on the willingness of a minor under 18 to engage in the commercial sex act. |

|

5.3 |

State law prohibits the criminalization of minors under 18 for prostitution offenses. |

|

5.4 |

State law provides a non-punitive avenue to specialized services through one or more points of entry. |

|

5.5 |

Child sex trafficking is identified as a type of abuse and neglect within child protection statutes. |

|

5.6 |

The definition of “caregiver” or another related term in the child welfare statutes is not a barrier to a sex trafficked child accessing the protection of child welfare. |

|

5.7 |

Crime victims’ compensation is specifically available to a child victim of sex trafficking or commercial sexual exploitation of children (CSEC). |

|

5.8 |

Victim-friendly procedures and protections are provided in the trial process for minors under 18. |

|

5.9 |

Child sex trafficking victims may vacate delinquency adjudications and expunge related records for prostitution and other offenses arising from trafficking victimization, without a waiting period. |

|

5.10 |

Victim restitution and civil remedies for victims of domestic minor sex trafficking or commercial sexual exploitation of children (CSEC) are authorized by law. |

|

5.11 |

Statutes of limitations for civil and criminal actions for child sex trafficking or commercial sexual exploitation of children (CSEC) offenses are eliminated or lengthened to allow prosecutors and victims a realistic opportunity to pursue criminal action and legal remedies. |

|

Section 6: Criminal Justice Tools for Investigation and Prosecutions (Legal Components) |

|

|

6.1 |

Training on human trafficking and domestic minor sex trafficking for law enforcement is statutorily mandated or authorized. |

|

6.2 |

Single party consent to audio taping is permitted in law enforcement investigations. |

|

6.3 |

Wiretapping is an available tool to investigate domestic minor sex trafficking and commercial sexual exploitation of children (CSEC). |

|

6.4 |

Using a law enforcement decoy to investigate buying or selling commercial sex is not a defense to soliciting, purchasing, or selling sex with a minor. |

|

6.5 |

Using the internet or electronic communications to investigate buyers and traffickers is a permissible investigative technique. |

|

6.6 |

State law requires reporting of missing children and located missing children. |

Table 1: Framework Brief.

As shown in Table 1, provisions of the protected innocence challenge legislative framework are considered critical elements in measuring a state’s progress towards eradicating domestic minor sex trafficking in the U.S. Section 5, Protective Provisions for Child Victims, is the longest section (11 components) and contains language around defining commercial sex, protecting minors from prosecution, and shielding them from practices that will not result in justice. The second longest section (10 components), Section 2, Criminal Provisions Addressing Demand, involves buyers of sex, which is a group that has historically rarely faced consequences for their role in commercialized sex with adults or children. Under this framework, statutes are intended to bring about harsh and just penalties for the sexual exploitation of minors by buyers. The three sections related to criminalizing DMST, traffickers, and facilitators are 4-6 components in length and are designed to penalize the act sex trafficking of domestic minors, to punish traffickers, and to punish those who benefit and/or promote child trafficking for sexual purposes, respectively. Last, Section 6, Criminal Justice Tools for Investigation and Prosecutions, is intended to equip law enforcement with tools to effectively investigate the commercial sexual exploitation of children and to report missing children as well as recovered children.

As can be seen in Table 2 [year 2018], 10 states earned the A grade; 25 states earned the B grade; 11 states earned the C grade; and 5 states earned the D grade. The A indicates a score between 90 to102.5; the B grade indicates a score between 80 to 89.5; the C grade indicates a score between 70 to79.5; and the D grade indicates a score between 60-69.5.

|

Sections |

Grade |

Criminali-zation of DMST |

Criminal Provisions Addressing Demand |

Criminal Provisions for Traffickers |

Criminal Provisions for Facilitators |

Protective Protections for Child Victims |

Criminal Justice Tools for Investigations& Prosecution |

Total |

|

Total Possible |

A |

10 |

25 |

15 |

10 |

27.5 |

15 |

102.5 |

|

Tennessee |

A |

10 |

25 |

15 |

9.5 |

22.5 |

14.5 |

96.5 |

|

Louisiana |

A |

10 |

25 |

15 |

10 |

20.5 |

15 |

95.5 |

|

Washington |

A |

10 |

24.5 |

15 |

9.5 |

23.5 |

12.5 |

95 |

|

Alabama |

A |

7.5 |

25 |

15 |

10 |

22 |

15 |

94.5 |

|

Florida |

A |

10 |

20.5 |

15 |

6 |

27.5 |

15 |

94 |

|

Kansas |

A |

10 |

22 |

14.5 |

9.5 |

23 |

15 |

94 |

|

Montana |

A |

8.5 |

25 |

15 |

7.5 |

23.5 |

12.5 |

92 |

|

Texas |

A |

10 |

25 |

15 |

7.5 |

18.5 |

15 |

91 |

|

N. Carolina |

A |

10 |

23 |

13 |

4.5 |

25 |

14.5 |

90 |

|

Oklahoma |

A |

10 |

24.5 |

15 |

7.4 |

21 |

12 |

90 |

|

Michigan |

B |

10 |

23 |

12.5 |

9.5 |

22 |

12.5 |

89.5 |

|

Utah |

B |

7.5 |

25 |

15 |

7.5 |

22 |

12.5 |

89.5 |

|

Minnesota |

B |

10 |

10 |

15 |

7.5 |

22.5 |

15 |

89 |

|

Colorado |

B |

10 |

23.5 |

12.5 |

7.5 |

20.5 |

14 |

88 |

|

Georgia |

B |

10 |

24.5 |

15 |

5 |

10 |

14.5 |

88 |

|

Mississippi |

B |

10 |

24.5 |

15 |

7.5 |

21 |

10 |

88 |

|

Nebraska |

B |

10 |

24 |

12 |

7.5 |

22 |

12 |

87.5 |

|

Kentucky |

B |

10 |

20.5 |

15 |

6 |

23 |

12.5 |

87 |

|

Missouri |

B |

7.5 |

23 |

15 |

9.5 |

20 |

12 |

87 |

|

Wisconsin |

B |

7.5 |

25 |

15 |

7.5 |

18 |

14 |

87 |

|

Massachusetts |

B |

10 |

21 |

15 |

7.5 |

21 |

12 |

86.5 |

|

Nevada |

B |

7.5 |

24 |

15 |

7.5 |

20 |

11.5 |

85.5 |

|

Oregon |

B |

10 |

21 |

15 |

7.5 |

17.5 |

14.5 |

85.5 |

|

Arkansas |

B |

10 |

22 |

15 |

10 |

13.5 |

14.5 |

85 |

|

Arizona |

B |

10 |

21 |

15 |

7.5 |

14.5 |

15 |

83 |

|

Delaware |

B |

10 |

20 |

15 |

5 |

18.5 |

14.5 |

83 |

|

New Hampshire |

B |

7.5 |

24 |

15 |

5 |

22.5 |

9 |

83 |

|

New Jersey |

B |

10 |

22 |

14.5 |

7.5 |

14.5 |

14.5 |

83 |

|

Illinois |

B |

10 |

20.5 |

14.5 |

7.5 |

17.5 |

12.5 |

82.5 |

|

Indiana |

B |

10 |

15 |

15 |

4.5 |

22.5 |

15 |

82 |

|

Pennsylvania |

B |

10 |

19.5 |

15 |

7 |

15.5 |

15 |

82 |

|

S. Carolina |

B |

10 |

21 |

11 |

6 |

24.5 |

9.5 |

82 |

|

W. Virginia |

B |

10 |

18.5 |

15 |

3.5 |

20 |

15 |

82 |

|

Iowa |

B |

7.5 |

23 |

15 |

6 |

15.5 |

14.5 |

81.5 |

|

Maryland |

B |

10 |

18.5 |

15 |

7.5 |

14 |

15 |

80 |

|

Connecticut |

C |

10 |

16.5 |

14.5 |

5 |

20.5 |

12.5 |

79 |

|

Ohio |

C |

9.5 |

18.5 |

14.5 |

4.5 |

17 |

15 |

79 |

|

Rhode Island |

C |

10 |

21 |

12.5 |

5 |

18 |

12 |

78.5 |

|

N. Dakota |

C |

10 |

16 |

15 |

5 |

21.5 |

10 |

77.5 |

|

Hawaii |

C |

10 |

17.5 |

15 |

9.5 |

13 |

11.5 |

76.5 |

|

California |

C |

10 |

15.5 |

13.5 |

3.5 |

21.5 |

12 |

76 |

|

Idaho |

C |

7.5 |

21 |

15 |

5 |

15.5 |

12 |

76 |

|

Alaska |

C |

7.5 |

17 |

15 |

9.5 |

11 |

14.5 |

74.5 |

|

Washington DC |

C |

7.5 |

17 |

9.5 |

7.5 |

22.5 |

9 |

73 |

|

Vermont |

C |

7.5 |

14.5 |

13.5 |

6 |

23.5 |

7 |

72 |

|

Virginia |

C |

7.5 |

17 |

12.5 |

5 |

14.5 |

14.5 |

71 |

|

New Mexico |

D |

7.5 |

17.5 |

13 |

7.5 |

12 |

12 |

69.5 |

|

South Dakota |

D |

8.5 |

17.5 |

15 |

7.5 |

11.5 |

9.5 |

69.5 |

|

Wyoming |

D |

10 |

12 |

12.5 |

5 |

21.5 |

7 |

68 |

|

New York |

D |

8.5 |

14 |

12.5 |

9 |

12 |

10 |

66 |

|

Maine |

D |

7.5 |

15 |

12.5 |

6 |

11.5 |

7.5 |

60 |

Table 2: States by Grades 2018.

As shown in Table 2, the 10 states with the A grade had a mean score of 93.25 (range: 90-96.5) for the six components. The B rated states (n=25) had a mean score of 85.08 (Range: 80-89.5) for the six components while the C rated states (n=11) had a mean score of 75.72 (range: 71-70) for the six components. Last, D rated states (n=5) had a mean score of 66.6 (range: 60-69.5) for the six components. These means indicate that all 50 states have enacted some criminal provisions for domestic minor sex trafficking, but not at the same level or with the same depth or progressiveness. All but 10 states, however, fell short in measuring up to the 41 provisions of the Protected Innocence Challenge Legislative Framework as evidenced by grades of B, C, D, or F. The lowest rated 16 states with C or D grades (including Washington DC) lag far behind peer states and must work harder to comply with recommendations for improvement in an effort to improve by one to three letter grades by next year’s measure. Thirty-five of the 50 states (excluding Washington DC) did earn A (n=10) and B (n=25) grades in 2018.As shown in Table 2, Tennessee, Louisiana, the state of Washington, Alabama, Florida, Kansas, Montana, Texas, North Carolina, and Oklahoma were the highest performing states in 2018 with A grades, while New Mexico, South Dakota, Wyoming, New York, and Maine were the lowest performing states in 2018 with D grades. As for reports of human trafficking, the World Population Review [18] reports that States with the highest number of reported human trafficking cases include:

- California(n=1656)

- Michigan(n=383)

- Georgia(n=375)

- Nevada(n=313)

- Illinois(n=296)

- North Carolina(n=287)

- Pennsylvania(n=275)

- Arizona(n=231)

- Washington(n=229)

- New Jersey(n=224)

North Carolina and Washington state are the only A grade states(for progress towards eradicating domestic minor sex trafficking) that rank among the top 10 states for high numbers of reported human trafficking cases in 2019, while the remaining 8 states are rated as B grades. These states may have high numbers of reported human trafficking cases for adults, but not minors. Given the A rating by the Protected Innocence Challenge Legislative Framework, which is child focused, it will not take into account their adult level human trafficking legislation. In the case of California, the number of reports must be viewed in the context of the size of the state’s population. As a whole, it is important to note that high numbers of reported cases of human trafficking in a state may be attributed to increased awareness about human trafficking instead of the lack of laws to protect victims or rampant trafficking activities.

COMPLEXITY OF ADDRESSING HUMAN TRAFFICKING

Not only is the arrest and prosecution of human trafficking cases complex, but so is the trafficker as a person and the relationship between the victim and the offender. Traffickers have varied kinds of relationships and roles and use varied methods of control [19]. These relationships, roles, and varied methods of control are later used to their advantage when the perpetrator later enters into the legal system and the victim is unwilling to cooperate in criminal proceedings. Traffickers’ methods of force include isolation/confinement, economic abuse, threats, emotional abuse, and physical abuse [20].Threats, abuse, and intermittent acts of kindness or affection result in trauma bonding whereby the victim grows close and attached to the trafficker [21]. This attachment or bond is then used to further control the victim [22]. Human traffickers do not have the “typical” profile as criminals due to the variability in their makeup. It is not possible to accurately describe them as cleanly as others deemed as “psychopathic” or “heinous” criminals although they are sometimes viewed just as psychopathic as others as perpetrators always on the prowl for the next victim [23]. Human traffickers are men and women, but men overwhelming make up those who are arrested and sentenced for human trafficking offenses [24]. They are friends, “boyfriends”, husbands, former victims, family members, gang members, and other organized crime members, smugglers, and employers with backgrounds, oftentimes, that include childhoods with an early introduction to sex and violence [25,26]. In her research, Roe-Sepowitz found that 24% (n=340) of men convicted of sex trafficking of minors had criminal histories related to violent crimes against a person (assault, battery, or robbery), property crimes (burglary, theft, or trespassing), and drug possession.

According to Farrell, Owens, and McDeavitt [27], new human trafficking laws are in existent in great numbers in every state in the U.S., but the number of cases actually prosecuted for human trafficking are few. The researchers argue that this is the case because human traffickers are often charged with lesser crimes; there is poor victim identification by law enforcement; there is a lack of support from high level law enforcement to frontline police officers; anti-trafficking policies are not measured for effectiveness; provisions of federal and state laws are not being enforced; there is confusion surrounding the interpretation of new laws; there is an over-reliance on lower level more established laws; and many state cases are turned over to federal authorities. Roe-Sepowitz [28] concurs with many of these assertions and adds that law enforcement tends to identify trafficking victims when it is reported to them not by professional training and assessment skills. She also explains that many state level cases are often turned over to federal authorities because many traffickers cross over several state lines while trafficking in persons.

DISCUSSION

The U.S. government is 19 years past the first federal legislation on human trafficking in this country the Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000. Since that time, all 50 states have implemented a variety of state human trafficking laws and taken actionable steps to address human trafficking. The State of Washington led the way in 2003. Many states have since taken broad and inclusive approaches to addressing human trafficking by enacting laws related to the criminalization of human trafficking; establishing criminal provisions for buyers, traffickers, and facilitators; attempting to specifically protect child victims; equipping law enforcement with tools to investigate and prosecute; allowing victims to vacate certain convictions; allowing victims to sue their traffickers; and increasing overall human trafficking awareness. The laws appear to be expansive across the 50 states as a whole while some struggle to reach the higher ends of the grade scale (A, B, C, D, F) or ranks (Tier 1, Tier 2, Tier 3 and Tier 4). Still, the message that the 50 states are sending out is that trafficking victims deserve justice because human trafficking denies the victim his or her human rights.

Despite the previously stated accomplishments in human trafficking laws, there appears to be problems with implementation, interpretation, and enforcement. The people who are charged with implementing new legislation at the various levels do not seem informed, comfortable, or supported enough to use the laws—or to their fullest capacity. Prosecuting trafficking cases is a lengthy process that requires the cooperation of law enforcement agencies, witnesses, human trafficking experts, forensic interview specialists, and informed criminal justice personnel to name a few. It requires risks and the courage to test out new laws. It requires an inordinate amount of preparation and team work. It requires keen negotiations, “hard balling” by prosecutors, and a deep understanding of the law and its many interpretations. Enforcing human trafficking laws is not easy given the nature of these newly existing laws, but is imperative that all states work diligently to take more steps to improve and implement their laws.

Legal efforts to address human trafficking must be dynamic and in constant state of growth, improvement, and innovation because human traffickers are always in a dynamic state of operations under the guise of entrepreneurship, faux relationships, and profit-making. Human traffickers have been successful at the exploitation of others because of their apparent understanding of a person’s need for love and attention; the power of force, fraud, and coercion; and ways to circumvent the legal system before and after detection by law enforcement. They seem to “bet” on the witness’ unwillingness to cooperate; the prosecutor’s likelihood of accepting a plea in order to secure a conviction even on a lesser charge; and law enforcement having a limited understanding of human trafficking laws, which carries severe penalties when actually enforced.

CONCLUSION

The literature indicates that hundreds of thousands of adults and minors are trafficked in the U.S. Yet, the statistics indicate that arrests, indictments, convictions, and sentencing are less than 2000 in number in any given year. Some may argue that the prevalence statistics are inflated or overestimated and that explains the incongruence. Others may argue that the laws are not having their intended effects because they are too new and underused. Still, some others may draw the conclusion that human trafficking is complex, clandestine, and too challenging to ever really eradicate on a grand scale despite criminal provisions. Regardless of where one stands on the probable causes of low arrests rates, indictments, convictions, and sentencing, human trafficking is real and is well documented throughout the U.S. Therefore, in addition to constantly working to improve implementation of human trafficking laws, the U.S. should consider increasing the forensic interviewing skills of human trafficking investigators, that include front line law enforcement officers, social service providers, prosecutors, and judges. More victim-centered investigations, from first point of contact, may result in more explicit testimonies and better outcomes in the court of law.

Human trafficking is a criminal activity that results in persistent human rights violations. As shown in this paper, criminal provisions at both the federal and state levels are imperative. Based on the fact that the federal government, Washington DC, and all 50 states have enacted laws to combat human trafficking, it is clear that the U.S. feels that human trafficking is a major problem that requires laws to formally address it. Now that the country has taken these major steps in an attempt to eradicate trafficking, it is time to fully implement and enforce these laws in the court of law at both the state and federal levels. It is time to improve all efforts to indict and convict human traffickers, facilitators, and buyers. The legal system is complex and laws are constantly up for interpretation. Despite these realities, human trafficking laws must be tested out in more human trafficking cases. Moreover, states that lack comprehensive laws that combat trafficking among adults and minors must work diligently to improve and implement their laws.

REFERENCES

- Troshynski EI, Blank JK (2008) Sex trafficking: An exploratory study interviewing traffickers. Trends in Organized Crime 11: 30-41.

- Victims of Trafficking and violence Protection Act of 2000. Public Law Page no: 106- 386.

- Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2003. Public Law Page no: 108-193.

- Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2005. Public Law Page no: 109-164.

- William Wilberforce Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2008. Public law Page no: 110-457.

- Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2013.

- One hundred fifteenth congress of the United States of America (2017) Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2017.

- Victims and Trafficking and violence protection Act of 2000.

- Shared Hope International Protected Innocence Challenge. Toolkit 2018. State action. National change.

- Lisa K (2017) Global estimates of modern slavery: Forced labor and forced marriage. International Labour Organization and Walk Free Foundation.

- Global Slavery Index.

- National Conference of State Legislatures (2018) Prosecuting human traffickers: Recent legislative enactments.

- Polaris 2014 State ratings on human trafficking laws.

- Human trafficking (2018). Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

- S. Department of Justice, Office of Public Affairs (2019) Department of Justice recognizes human trafficking prevention month and announces updates to combat this violent crime.

- National Conference of State Legislatures (2018). Prosecuting human traffickers: Recent legislative enactments.

- Shared Hope International Protected Innocence Challenge. Toolkit 2018, State action, National change, Washington DC.

- World Population Review (2019) Human trafficking statistics by state 2019.

- Serle CMB, Krumeich AM, Van Dyke A, De Ruiter E, Terpstra L, et al., (2017) Sex traffickers’ views: A qualitative study into their perceptions of the victim-offender relationship. Journal of Human Trafficking 4: 169-186.

- Polaris 2018 statistics from the National human trafficking hotline (2019).

- Meshelemiah JCA, Lynch RE ( 2019) The cause and consequence of human trafficking: Human rights violations. Press book, Columbus, The Ohio State University.

- Mehlman Orozco K (2017) Projected heroes and self-perceived manipulators: Understanding the duplicitous identities of human traffickers. Trends in Organized Crime Page no: 1-20.

- Lopez DA, Minassians H (2018) The sexual trafficking of juveniles: A theoretical model. Victims & Offenders 13: 257-276.

- Broad R (2015) ‘A vile and violent thing’: Female traffickers and the criminal justice response. British Journal of Criminology 55: 1058-1075.

- Jordan J, Patel B, Rapp L (2013) Domestic minor sex trafficking: A social work perspective on misidentification, victims, buyers, traffickers, treatment, and reform of current practice. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment 23: 356-369.

- Mehlman Orozco K (2017) Projected heroes and self-perceived manipulators: Understanding the duplicitous identities of human traffickers. Trends in Organized Crime Page no: 1-20.

- Farrell A, Owens C, McDevitt J (2014) New laws but few cases: Understanding the challenges of the investigation and prosecution of human trafficking cases. Crime, Law and Social Change 61: 139-168.

- Roe Sepowitz D (2019) A six-year analysis of sex traffickers of minors: Exploring characteristic and sex trafficking patterns. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment 29: 608-629.

Citation: Meshelemiah JCA (2019) Criminal Provisions for Human Trafficking: Rankings, State Grades, and Challenges. Forensic Leg Investig Sci 5: 036.

Copyright: © 2019 Meshelemiah JCA, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.